California Water Commission rolls out the draft regulations for the Water Storage Investment Program

California Water Commission rolls out the draft regulations for the Water Storage Investment Program

With the passage of Prop 1, the California Water Commission was appropriated $2.7 billion to pay for public benefits for water storage projects. The Commission has been developing regulations that will specify how the money will be disbursed. Those draft regulations were presented a public meeting in October in Lafeyette.

With the passage of Prop 1, the California Water Commission was appropriated $2.7 billion to pay for public benefits for water storage projects. The Commission has been developing regulations that will specify how the money will be disbursed. Those draft regulations were presented a public meeting in October in Lafeyette.

Jenny Marr, Supervising Engineer for the Commission and Project Manager for the Water Storage Investment Program, began by noting that Proposition 1 passed in November of 2014 which appropriated $2.7 billion to the Commission to fund the public benefits of water storage projects; eligible water storage projects must improve the operation of the state water system, be cost-effective, provide a net improvement in ecosystem and water quality conditions.

Jenny Marr, Supervising Engineer for the Commission and Project Manager for the Water Storage Investment Program, began by noting that Proposition 1 passed in November of 2014 which appropriated $2.7 billion to the Commission to fund the public benefits of water storage projects; eligible water storage projects must improve the operation of the state water system, be cost-effective, provide a net improvement in ecosystem and water quality conditions.

Prop 1 provides funding for the public benefits of a broad range of both surface and groundwater storage projects: The Cal-Fed surface storage projects; groundwater storage projects; groundwater contamination prevention or remediation projects with storage benefits; conjunctive use projects; reservoir reoperation projects; local surface storage projects; and regional surface storage projects. These various project types are specified in the language of Prop 1 and defined in more detail in the regulations under the definition section, Ms. Marr noted. “As you can see, it’s a broad group of project types, from small to large throughout the state, as big as the Cal Fed surface storage projects to a small as local groundwater, so we’re trying to develop this program with some flexibility and scalability to fit all these types of projects,” she said.

The public benefits that are defined by the statute are ecosystem improvements, water quality improvements, flood control, emergency response, and recreation. “These public benefits are defined in the regulation that you have in front of you, and we want to stress that these are the fundable public benefits for Prop 1 money, but they are not the only types of benefits that water storage can provide,” said Ms. Marr. “So the Water Commission and Prop 1 funding is a cost share partner. There’s other beneficiaries, there are other cost share partners that are funding benefits such as water supply or hydropower or other benefits of storage.”

The public benefits that are defined by the statute are ecosystem improvements, water quality improvements, flood control, emergency response, and recreation. “These public benefits are defined in the regulation that you have in front of you, and we want to stress that these are the fundable public benefits for Prop 1 money, but they are not the only types of benefits that water storage can provide,” said Ms. Marr. “So the Water Commission and Prop 1 funding is a cost share partner. There’s other beneficiaries, there are other cost share partners that are funding benefits such as water supply or hydropower or other benefits of storage.”

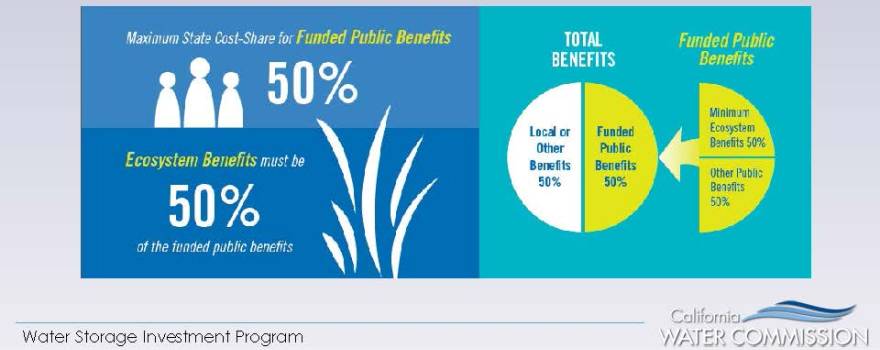

There are also two cost share rules specified in Prop 1: the maximum amount the Commission can fund is up to 50% of the total project cost, and of the amount that is funded for public benefits, 50% of those benefits must be ecosystem benefits. “So to even be eligible, your project has to provide ecosystem improvements and that’s going to set the bar for how much, up to 50%, the Commission can cost-share,” she pointed out.

There are also two cost share rules specified in Prop 1: the maximum amount the Commission can fund is up to 50% of the total project cost, and of the amount that is funded for public benefits, 50% of those benefits must be ecosystem benefits. “So to even be eligible, your project has to provide ecosystem improvements and that’s going to set the bar for how much, up to 50%, the Commission can cost-share,” she pointed out.

Another requirement of Prop 1 is that any project funded by the Commission has to provide measurable improvements to the Delta ecosystem or tributaries to the Delta. “This is one of the key eligibility requirements of this program – if you are an eligible project and an eligible applicant, you still have to make sure that your project provides measurable improvements to the Delta or the tributaries to the Delta,” she said.

The statute requires the Commission to select projects through a competitive public process. “What we interpret competitive to mean is that we see all the projects at once, so right now there’s only one planned solicitation, but that could change in the future, depending on the amount of eligible projects and the amounts requested,” Ms. Marr said.

“The public process is very important because we want to be visible,” she said. “We’ve done a lot of public meetings in this first year and we’re going to continue that process. Every Commission meeting is public. It’s noticed 10 days in advance so you know what the Commission is going to be talking about, and any decision that the Commission makes on any project or any review of any project will be done in a public forum.”

The program is called the Water Storage Investment Program, or WSIP for short. The Commission is going to adopt these regulations by December 15, 2016, so there’s still a lot of time left in the process, noted Ms. Marr. The statute required these regulations to include the quantification of public benefits and the management of public benefits. Program guidelines, application requirements, and details on the process have also been added to the regulations, she said.

The December 15, 2016 date is not only the day that the Commission will need to adopt the regulations, but it’s also the first day that the Commission can spent any money on projects, she said. “A lot of folks have asked, ‘Why aren’t you funding projects now? We’re in a drought and we really need this money and we’ve got projects ready to go.’ But the statute didn’t release any of this money for projects until December 15, 2016, so although we’re in the throes of a four year drought, this money was not for the immediate needs. It’s for planning for the future, for the next drought, and really allowing project proponents and the Commission to be strategic about future needs in the state.”

She presented a slide showing the three-year timeline for the project, noting that in 2015, they held public meetings and stakeholder advisory committee meetings, and developed draft regulations. “We’ve really tried to develop the content and formulate this program with public input and stakeholder input, so the draft that you see in front of you has been worked on over several months,” she said.

She presented a slide showing the three-year timeline for the project, noting that in 2015, they held public meetings and stakeholder advisory committee meetings, and developed draft regulations. “We’ve really tried to develop the content and formulate this program with public input and stakeholder input, so the draft that you see in front of you has been worked on over several months,” she said.

At the end of this year, the Commission will approve a version of the draft regulations to start the formal rulemaking process, which is just the start of the process, Ms. Marr said. “Once the commission adopts or approves a version of the regulations, we’ll submit a package to the Office of Administrative Law, and once that package is published in the California Regulatory Notice Register, that’s when we start this formal rulemaking process, and that could be all of 2016.”

The formal rulemaking process follows the Administrative Procedures Act, which allows up to a year to complete the formal rulemaking process, she said. “Once we start this process, the first thing that happens is there’s a 45-day public comment period. And any comments received during that period are considered formal comments and the commission and commission staff have to respond to every single one of those comments,” she said. “Also during that 45-day public comment period, we’ll be doing public hearings where we’ll be taking verbal comments on the regulation. So at a maximum, this formal rulemaking process could take up all of 2016, but at a minimum, it would be that 45-day public comment period. Any time a change is made to the regulation, we have to open up a new comment period, and that could be anywhere from 15 to another 45 days.”

The formal rulemaking process follows the Administrative Procedures Act, which allows up to a year to complete the formal rulemaking process, she said. “Once we start this process, the first thing that happens is there’s a 45-day public comment period. And any comments received during that period are considered formal comments and the commission and commission staff have to respond to every single one of those comments,” she said. “Also during that 45-day public comment period, we’ll be doing public hearings where we’ll be taking verbal comments on the regulation. So at a maximum, this formal rulemaking process could take up all of 2016, but at a minimum, it would be that 45-day public comment period. Any time a change is made to the regulation, we have to open up a new comment period, and that could be anywhere from 15 to another 45 days.”

The purpose of the formal rulemaking process is to provide meaningful opportunity for public input, Ms. Marr said. “So we really want to solicit public input on these regulations,” she said. “It also provides sufficient notice to the regulated community – those folks that are actually going to be doing applications and that are project proponents.”

Once the formal rulemaking process is complete, the regulations would be reviewed and approved by the Office of Administrative Law with the Commission adopting the regulation by December 15, 2016.

Solicitation of projects is penciled in for 2017. “At previous public meetings, we talked about potentially shifting up the schedule if we were able to make it through the formal OAL process quickly, but some of the feedback we’ve received from project proponents is that it would make it hard for them; if we make it through the process quicker to give them more time to do the application and finish plan formulation,” she said. “So at this point in time, we’re looking at this as a pretty close schedule to what the actual solicitation period is going to be.”

In early 2017, the Commission will begin the first step of a two-step application process, being the pre-application process. “A pre-application is early notice to the Commission about the projects that are out there, who the applicant is, what the potential project benefits are, and some very preliminary information,” she said, noting that there are several reasons for the pre-application process. “It’s early information for the Commission so they get a sense of what projects may be applying, it allows applicants to see other potential project proponents for potentially integrating projects or prioritizing projects in the region, and it also allows the applicants to hear about any issues or fatal flaws that their project might have.”

Once the pre-application period is over, the full application development period will start, which they are anticipating to be about six months. “So 2017 is mostly the project solicitation phase where it’s really on the project proponent to do their work,” she said. “In 2018 will be the technical review, the independent peer review, and the Commission’s decision time, so we’ve got a lot of process ahead of us, but we’re going to streamline it as much as possible, and provide as much technical assistance as needed, and really try to help the Commission make their decisions.”

The draft regulations

The Commission will be producing regulations which give the information on how to quantify and manage their benefits and the ground rules for the program; they will also be providing application instructions which will provide the details for filling out the applications, the due dates, and the workshop dates, Ms. Marr said. They are also developing a technical appendix to accompany the instructions.

“We realize that when you read the regulations, it’s going to sound like a heavy lift for a lot of projects, and it is, and we admit that,” Ms. Marr said. “We know it’s very complex; these projects are going to be complex because water management in California is complex, so we’re really going to try to provide as much technical guidance as possible.”

She then discussed each of the sections of the draft regulations:

Section 6000 – Definitions: A lot of definitions have been included at the request of the stakeholder group, she said. “Just to make sure that there’s clarity within the regulations, we’ve included all definitions that we’ve received any questions on.”

Section 6001 – General Provisions: This section mostly deals with who the eligible applicants are and what projects are eligible.

Section 6002 – General Selection Process: This section describes the two-step application process, and the multiple step review process that each application will go through that includes a completeness and eligibility check, a technical review, an independent peer review, and then finally the Commission’s decision process.

Section 6003 – Funding Commitments: The funding commitments section details all of the steps from conditional funding commitment to a final funding commitment, once the Commission has made their decision.

Section 6004 – Quantification of Public Benefits: This section is rather technical, Ms. Marr acknowledged. “We’ve tried to provide a clear framework for how benefits can be quantified, but one of the things we wanted to do is to keep that section flexible,” she said. “There are many ways to quantify public benefits, there’s not one right answer. … I call it an apples to oranges comparison because we’re not going to get exactly the same thing, but as long as we can stay in the fruit realm, at least we can make some decisions on it and make sure that everyone’s at least at the same level.”

Section 6005 and 6006 – Ecosystem and water quality priorities and relative environmental value: Ms. Marr noted that this is the topic of the second half of the presentation.

Section 6007 – Managing public benefits: “That’s really an important part of these regulations and what the Commission is trying to do because it’s really managing those public benefits that ensures that these public benefits are provided over the life of the project,” Ms. Marr said. “We want to make sure that these public benefits are resilient to changing futures and that benefits that are claimed now will be resilient to climate change, or new conditions, and really wanting to make sure that this public investment with public funds are spent well.”

Other things that are required for managing the public benefits is documentation of those benefits, and adaptive management, she said. “If you have your project operations and conditions change in the future, or you’re not hitting your public benefits targets, what are you going to do about it, what decisions are you going to make? So we’re asking folks to provide some sort of monitoring assurances and reporting planning.”

She also noted that the statue requires that project proponents enter into contracts with the public agency managing those benefits – Department of Water Resources, Department of Fish and Wildlife, and/or the State Water Board – to make some commitments on how these public benefits will be managed in the future.

The floor was then opened up for questions.

One audience member asked who was on the stakeholder advisory committee. “It’s a group of 35 organizations that bridge a cross-section of potential project proponents, interest groups and organizations representing agriculture, environment, human right to water, so environmental justice, we had a large suite of stakeholders involved that crossed a lot of interests,” replied Ms. Marr. “That is posted on our website, if you want to see the roster of the stakeholder advisory committee.”

Another audience member asked what was meant by the term, ‘continuous appropriation’. Rachel Ballanti, Assistant Executive Officer for the Commission, explained, “Most of the money that was in the bond was dedicated to specific purposes and specific agencies to administer grant programs, but during the annual budget cycle, those agencies would go to the legislature and ask for a specific amount to be allocated to their program for that fiscal year. What continuous appropriation means is that the Commission doesn’t have to go back to the legislature each year to ask for a specific portion of that $2.7 billion for that year, so it creates a little bit more flexibility, especially when dealing with large projects or potentially large projects.”

Attendee who identifies himself as an engineer asks who the Commission is anticipating to be project proponents. “You stated you have a high-bar for what an applicant needs to do in order, but we’re talking about non-profits and Indian tribes, so who did you expect to be an applicant?”

“There are certain levels of expectation for certain applicants,” replied Jenny Marr. “Applicants for projects such as the CalFed projects which has been studied for a long time, there’s a high level of technical capacity there – the Contra Costa Water District, Sites JPA, the being developed Friant JPA, those are potential applicants with a high level of sophistication. Within the regulations, we’ve tried to set minimum requirements … there are areas of flexibility within the regulation that say if you don’t think this is applicable to your project, or it may not be a necessary analysis due to the size of the project, you can qualitatively describe some things so we’ve tried to set at least minimum bars for some of the smaller agencies that would apply for funding. The bar gets raised for a level of sophistication based on the technical complexity of the project.”

The same audience member then asks about permits. “I’m reading here, ‘specifically each funding recipient shall demonstrate the following items of the water code have been completed: environmental documentation associated have been completed, all required permits have been secured.’ That’s pretty clear, but the next section then talks about funding for permits and it looks like there is some funding mechanism where you can help people acquire permits, but we’re not talking about any funding until 2017, so how does that work?”

“There’s some timing, so when the applications come in, the requirements for content in the application are completed feasibility studies but only a draft environmental document; you don’t have to have any of your permits at the time you apply,” said Ms. Marr. “The Commission is going to make a conditional funding commitment that states the amount of money based on the public benefits claimed at this point in time that the Commission will set aside for your project. Then there could be a variable amount of time between the conditional commitment to a final condition while projects are working on their final environmental document, securing all their permits, and doing a list of other approvals and necessary operations, finalizing their operations, getting into contracts with the public agencies, so there’s a list of things that has to happen between the conditional funding commitment and the final funding commitment, so part of that ask in your conditional funding commitment could be a request for assistance in permitting, so that would happen in that post-conditional before final commitment stage.”

He asks how CEQA fits into this.

“For this program, the requirement for application is a public draft CEQA document, so you could still be in your draft phases but to actually encumber funds and start receiving any reimbursement, you’ve got to have your final CEQA document completed,” said Ms. Marr

Ecosystem and water quality priorities and their relative environmental values

Jenny Marr then set the stage for the presentation of priorities and the relative environmental values. The language in Prop 1 directs the Department of Fish and Wildlife to provide priorities and relative environmental values for ecosystem improvements, and directs the State Water Board to provide priorities and relative environmental values for water quality improvements.

Ms. Marr explained the meaning of the terms ‘priorities’ and ‘relative environmental values.’ “If I was a project applicant, I would look at the priorities and think about how I could formulate my project to achieve any of the priorities that were set forth by the Fish and Wildlife or the State Board, so I would use these priorities to formulate my project,” she said. “Once the applications come in to the Commission, part of the review team will be Fish and Wildlife staff and State Board staff and we’ll be working together to determine a relative environmental value for the project, so we’re not going to be asking project proponents to determine the relative environmental value, but that is something that the staff and technical review team will be doing.”

The upcoming presentations will describe the criteria for the relative environmental values. “The technical review team will be evaluating each of these criteria to come up with a relative environmental value, and that relative environmental value will be project versus project,” she said. “It will likely be something that’s high, medium, and low for relative environmental value on ecosystem improvements and water quality improvements.”

Ecosystem improvement priorities

“Ecosystem improvements” are currently defined in the draft regulations as:

“a public benefit that protects, restores, or enhances ecosystems, and contributes to the restoration of aquatic ecosystems and native fish and wildlife. Ecosystems include both aquatic and terrestrial habitats and natural communities. Per Water Code Section 79753(a)(1), ecosystem improvements may include changing the timing of water diversions, improvement in flow conditions, temperature, or other benefits that contribute to the restoration of aquatic ecosystems and native fish and wildlife, including those ecosystems and fish and wildlife in the Delta.”

Scott Cantrell, Chief of Water Branch Department of Fish and Wildlife, then presented the ecosystem priorities that have been defined by the Department of Fish and Wildlife. He noted that the content of the priorities has remained essentially the same over the last several months, although they have condensed the number of priorities and modified the language to make them more concise and understandable to applicants.

Scott Cantrell, Chief of Water Branch Department of Fish and Wildlife, then presented the ecosystem priorities that have been defined by the Department of Fish and Wildlife. He noted that the content of the priorities has remained essentially the same over the last several months, although they have condensed the number of priorities and modified the language to make them more concise and understandable to applicants.

The priorities are grouped into two broad categories: The first category is flow and water quality, and the second category addresses physical processes and habitat. Mr. Cantrell then described the priorities and gave some examples.

Flow and water quality improvements

“As we know by best available science, flow and water quality are key drivers of fish species abundance, distribution, and overall viability of populations,” he said. “The magnitude, timing, duration, and stability of flows are critical to the overall survival of native fish and wildlife, so projects that can be operated to emulate a more natural hydrograph and provide appropriate water quality conditions that will support native fish and wildlife populations is one of our key priorities.”

The first three priorities on the list pertain to the pattern and magnitude of flows, and natural hydrograph:

1. Provide cold water at times and locations to increase the survival of salmonid eggs and fry.

2. Enhance flows to improve habitat conditions for in-river rearing and downstream migration of juvenile salmonids.

3. Maintain flows and appropriate ramping rates at times and locations that will minimize dewatering of salmonid redds and prevent stranding of juvenile salmonids in side channel habitat.

The next two priorities deal with water quality and upstream passage of migratory fish. “These are factors such as water quality constituents of temperature, dissolved oxygen, nutrients, and salinity,” he said. “These are also shared priorities of the State Water Board as essentially higher flows can improve water quality. Fast moving water tends to maintain more dissolved oxygen and is colder, and these are all conditions that are conducive to healthy fish populations.”

Increase flows to improve ecosystem water quality.

5. Increase flows to support anadromous fish passage by providing adequate dissolved oxygen and lower water temperatures.

The next two priorities are aimed at enhancing attraction flows for migratory fish. “We know that fish that can key in on the scent of water in which they spawned will be attracted to those watersheds,” he said. “Those are called the natal streams, and so providing higher flow on those streams will help the fish cue in on those natal streams. Also Delta outflow is important for Delta smelt, longfin smelt, and other estuarine fishes.”

6. Increase attraction flows during the upstream migration period to reduce straying of anadromous species into non-natal tributaries.

7. Increase Delta outflow to provide low salinity habitat for Delta smelt, longfin smelt and other estuarine fishes in the Delta, Suisun Bay, and Suisun Marrsh.

The last priority on the list pertains to groundwater and surface water interconnection. “The intent here is that we like projects to formulate, where applicable, operations that will improve in stream flow benefits for fish and wildlife to maintain conditions conducive for migration and rearing of fish, and also to support riparian vegetation,” he said. “These are things like creating surface wetlands, meadows, springs, and seeps to provide habitat for aquatic plants and animals.”

8. Maintain groundwater and surface water interconnections to support instream benefits and groundwater dependent ecosystems.

Physical processes and habitat priorities

Mr. Cantrell then described the priorities for physical processes and habitat. The first three priorities are aimed at enhancing flow regimes, floodplains, and habitat diversity to support fish and wildlife. “Over last 150 years, we know the landscape has been substantially altered through channel and floodplain modification and so on, and that floodplain is a very beneficial habitat for rearing and growth of young fish species, so project operations that can increase the frequency, magnitude, and duration of floodplains in a priority of the Department. And these enhanced floodplains provide other ancillary ecosystem benefits.”

1. Enhance flow regimes to improve the quantity and quality of riparian and floodplain habitats for aquatic and terrestrial species.

2. Enhance floodplains by increasing the frequency, magnitude, and duration of floodplain inundation to enhance priMarry and secondary productivity and the growth and survival of fish.

3. Enhance the temporal and spatial distribution and diversity of habitats to support all life stages of fish and wildlife species.

The next two priorities are aimed at improving fish passage and downstream migration by reducing barriers to migration and entrainment into diversions. “These are the types of actions to provide for increased access to natal streams, putting on state of the art fish screens on unscreened diversions, and reducing entrainment overall of the fish to improve fish survival.

4. Enhance access to fish spawning, rearing, and holding habitat by eliminating barriers to migration.

5. Remediate unscreened or poorly screened diversions to reduce entrainment of fish.

The next two priorities pertain to providing water for riparian and wetlands habitat, including managed wetlands, as well as to control non-native invasive species. “We know that wetlands and riparian habitats are very critical to migratory birds on the Pacific Flyway, neotroprical migrants, and a variety of other native species, and providing water to these habitat types increases their area, availability and connectivity. We also know that reducing the impacts of invasive species on natives can reduce competition and provide more physical space for native species.”

6. Provide water to enhance seasonal wetlands, permanent wetlands, and riparian habitat for aquatic and terrestrial species on state and federal wildlife refuges and on other public and private lands managed for ecosystem values.

7. Develop and implement non-native invasive species management plans utilizing proven methods to enhance habitat and increase the survival of native species.

The final priority in this category is to enhance habitat for native species that have commercial, recreational, and scientific and educational value.

8. Enhance habitat for native species that have commercial, recreational, scientific, and educational value.

“These are all core values of the Department of Fish and Wildlife and they are part of our mission,” Mr. Cantrell concluded.

Water quality improvements

The term ‘water quality improvements’ is defined in the draft regulations as:

“a public benefit that includes water quality improvements that provide significant public trust resources in the Delta or in other river systems, or water quality improvements that clean up or restore groundwater resources, per Water Code Section 79753(a)(2).”

Gail Linck, Environmental Program Manager with the State Water Board, then presented the water quality improvement priorities. “The State Water Board has identified nine draft priorities,” she said. “The water quality priorities that I’m going to provide an overview do not represent all of the water board’s priorities, but they are those that we’ve identified as having the potential to positively be influenced by water storage projects. We recognize the importance of the connections between water quality and quantity and also the connections between water quality and ecosystem benefits.”

Gail Linck, Environmental Program Manager with the State Water Board, then presented the water quality improvement priorities. “The State Water Board has identified nine draft priorities,” she said. “The water quality priorities that I’m going to provide an overview do not represent all of the water board’s priorities, but they are those that we’ve identified as having the potential to positively be influenced by water storage projects. We recognize the importance of the connections between water quality and quantity and also the connections between water quality and ecosystem benefits.”

The first five priorities address water quality parameters for waters in the state listed as impaired. “This means they are not meeting their water quality objectives and are on the list of impaired water bodies under the Clean Water Act, Section 303d. The parameters for these water bodies are temperature, dissolved oxygen, nutrients, mercury, and salinity,” she said. “All these water bodies are listed and posted on the Commission’s website if you’re interested in the details.”

“You will probably notice that these parameters are often related to each other with regard to a water storage project design or operations,” added Ms. Linck. “For example, flows will affect several of these parameters, and we can see improvements that would address one or more of these priorities.”

1) Improve water temperature conditions in water bodies on California’s Clean Water Act (CWA) Section 303(d) list that are impaired for temperature.

2) Improve dissolved oxygen conditions in water bodies on California’s CWA 303(d) list that are impaired for dissolved oxygen.

3) Improve nutrient conditions in water bodies on California’s CWA 303(d) list that are impaired for nutrients.

4) Improve mercury conditions in water bodies on California’s CWA 303(d) list that are impaired for mercury.

5) Improve salinity conditions in water bodies on California’s CWA 303(d) list that are impaired for sodium, total dissolved solids, chloride, or specific conductance/electrical conductivity.

The remaining priorities pertain to water quality improvements associated with groundwater, stream flows, water demand, and the human right to water:

6) Protect, clean up, or restore groundwater resources in CASGEM high- and medium-priority basins.

7) Achieve Delta tributary stream flows that resemble natural hydrograph patterns or other flow regimes that have been demonstrated to improve conditions for aquatic life.

8) Reduce current or future water demand on the Delta watershed by developing local water supplies.

9) Provide water for basic human needs, such as drinking, cooking, and bathing, in disadvantaged or similarly situated communities, where those needs are not being met.

Relative environmental values for ecosystem priorities

Scott Cantrell then described the relative environmental values which are in Section 6006 of the regulation. “We recognize that projects will make contributions to these priorities and ecosystem benefits in various ways, and they will vary greatly,” he said. “So what we’re going to be looking at in these project proposals are specific information such as the number and magnitude and mix of benefits, the location and timing of benefits, and how long these benefits persist. And that we’ll also need to see clearly stated goals and objectives for ecosystem improvements, including monitoring and adaptive management programs and strategies to provide for resilience in the face of climate change.”

1) Number of ecosystem priorities addressed by the project. “The general idea is that the more priorities a project can incorporate, the better,” he said.

2) Magnitude and certainty of ecosystem improvements. “Magnitude is essentially defined as the quantity and scale of the improvement,” he clarified. “Certainty is the conventional sense of certainty; it’s the likelihood of successful outcomes.”

3) Spatial and temporal scale of ecosystem improvements. “These are the conventional meanings of space and time, so spatial scale refers to the geographical dimensions of the improvement and temporal scale is the scheduled time in which the improvement would occur,” he said.

4) Inclusion of an adaptive management and monitoring program that includes measurable objectives, performance measures, thresholds and triggers for managing ecosystem benefits. “There is a requirement to manage public benefits over time, so it’s going to be important in order to evaluate these ecosystem outcomes, to have some way to assess the status and trends towards progress achieving these improvements, as well as thresholds and triggers should these improvements not be playing out as planned.”

5) Immediacy of ecosystem improvement actions and realization of benefits. “This is basically when does the improvement begin to show up, and when would the accrual of benefits occur over time.”

6) Duration of ecosystem improvements. “How long is the project going to be providing those benefits.”

7) Consistency with species recovery plans and strategies, initiatives, and conservation plans.

8) Location of ecosystem improvements and connectivity to areas already being protected or managed for conservation values. “This is the idea of providing interconnected habitats and migration corridors for species and also providing larger blocks of protected areas where possible, so its large areas and interconnected habitats that we’re aiming at in this relative environmental value,” he said.

9) Efficient use of water to achieve multiple ecosystem benefits. “If there’s a block of water that could do double or triple duty to have large outcomes with small amounts of water, that would be the ideal situation, so for example, water released from an upstream reservoir, if that block of water could provide an instream flow benefit of cold water, and then be used for downstream seasonal wetlands and then also be conjunctively recharged to depleted groundwater aquifer, that would be an example of an efficient use of water.”

10) Resilience of ecosystem improvements to the effects of climate change. “These are things that we know are going to change, such as hydrology, increasing water temperatures, sea level rise, and salinity intrusion in the Delta, so we felt this was a very important relative environmental value that a project could address.”

Relative environmental values for water quality improvements

Gail Linck then discussed the relative environmental values for water quality priorities and where they differ from the relative environmental values for ecosystem priorities.

The first six relative environmental values for water quality improvements are the same as the first six for ecosystem values. “We’ve determined that these same types of values would also apply to water quality improvements,” she said.

1) Number of water quality priorities addressed by the project.

2) Magnitude and certainty of water quality improvements.

3) Spatial and temporal scale of water quality improvements.

4) Inclusion of an adaptive management and monitoring program that includes measurable objectives, performance measures, thresholds, and triggers for managing water quality benefits.

5) Immediacy of water quality improvement actions and realization of benefits.

6) Duration of water quality improvements.

The next priorities differ from the ecosystem priorities:

7) Consistency with water quality control plans, water quality control policies, and the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (2014).

8) Connectivity of water quality improvements to areas that support beneficial uses of water or are being managed for water quality. “We realize that improvements from a water storage project that are adjacent to an area that already is improved is better than an isolated improvement that is separate from,” Ms. Link said.

9) Resilience of water quality improvements to the effects of climate change.

10) Extent to which water quality improvement provides water for basic human needs, such as drinking, cooking, and bathing, in disadvantaged or similarly situated communities, where those needs are not being met.

11) Extent to which undesirable results that are caused by groundwater extractions are addressed.

Next steps

The public is welcome to submit comments on the draft regulations. The comments received right now are informal comments; the formal comment period will begin once the rulemaking process is initiated at the Office of Administrative Law.

In early 2016, the Water Commission will solicit concept papers. “So if you’re a project proponent, start thinking about how your project might operate, where is it at, where is it getting its water from, and what are potential public benefits,” Jenny Marr said. “This isn’t going to be a detail; it’s a concept paper, just a qualitative description over a couple pages at most. It will not be a heavy lift and it’s not required but it helps us formulate our process and our program a little bit better, and helps you to have some interaction with us to identify potential eligibility issues, or flaws.”

As the regulation makes its way through the formal rulemaking process, Commission staff will be working on application instructions and technical guidance; when those are in draft form, workshops will scheduled.

There is opportunity for further participation at the California Water Commission meetings which occurs on the third Wednesday of every month; the meeting is open and webcast. There is opportunity for public comment after every agenda item and the Water Storage Investment Program is discussed at every meeting.

“These aren’t the only places you should be participating,” said Jenny Marr. “We’ve said today, the Commission is a cost-share partner, so there are other folks involved. Project proponents are going to be formulating their projects, and in most cases, it’s going to be public agencies and water suppliers, so attend their board meetings and work closely with them to ensure that your concerns are being met and the projects are formulated to achieve the objectives that you locally have. So not only participate in our process but participate on the local end as well.”

For more information …

- Click here for the full power point presentation.

- Click here for the draft regulations.

- Click here for the webcast.

Get the Notebook blog by email and never miss a post!

Get the Notebook blog by email and never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!