Pricing, programs, pleading, prohibiting, pressuring, and plastering … what’s the most effective approach to get consumers to use less? UC Riverside’s Ken Baerenklau reviews the latest research

Pricing, programs, pleading, prohibiting, pressuring, and plastering … what’s the most effective approach to get consumers to use less? UC Riverside’s Ken Baerenklau reviews the latest research

As the state enters a fourth year of drought and reservoirs continue to drop precipitously low, the calls for conservation will only grow louder and more frequent as water agencies struggle to meet customer demands. In an effort to encourage their customers to conserve, water agencies have been adopting and implementing a wide variety of programs in an effort to bring down demand. Which ones are effective?

At the National Water Research Institute’s 2015 Drought Response Workshop, Professor Ken Baerenklau from UC Riverside School of Public Policy gave a presentation on the latest research on the effectiveness approaches to reducing consumer demand. (In utility-speak, they call this “Demand-Side Management,” a term coined by the energy companies during the energy crisis in the 1970s, but you can just think about them as water conservation programs and policies.)

Ken Baerenklau began by saying that in his presentation, he would summarize what is known about the various demand-side management approaches, demonstrate the importance of accounting for customer responses for whatever policies are put in place, and emphasize that agencies really need to study their customers if they want to have a chance of predicting the real effects of their policies when put into practice.

whatever policies are put in place, and emphasize that agencies really need to study their customers if they want to have a chance of predicting the real effects of their policies when put into practice.

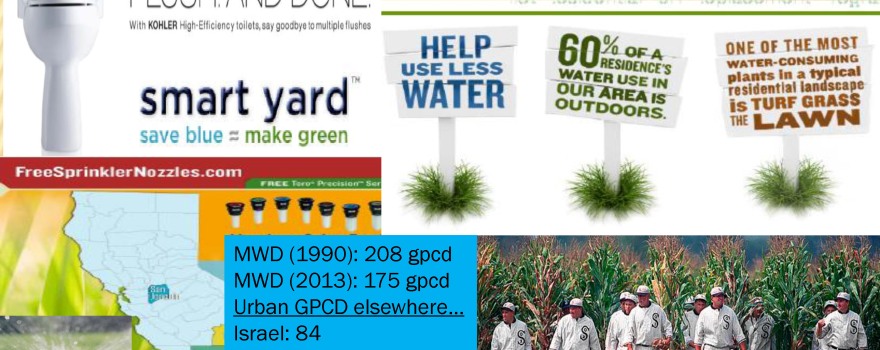

“In order to get through that, I’ve organized myself around the six “Ps” of demand side management,” he said. “We’re going to talk about pricing, programming, encouraging the use of conservation practices of different kinds, pleading with your customers to voluntarily reduce their water consumption, prohibiting different activities, pressuring them into doing them by using social norms and shaming of different approaches, and finally, plastering, or an education and information campaign.”

Pricing

Mr. Barenklau started with what is known on pricing from the literature. “If you don’t’ believe this first one, you should,” he said. “There is ample evidence that customers respond to price changes. And furthermore, pricing is actually a great cost-effective means of achieving conservation goals. The cost effectiveness derives from the flexibility that you afford your customers to respond to this incentive that they see as being optimal for their own situation.”

It’s about social costs and about social welfare, not just a budgetary cost, he said. “The pricing elasticity of water demand, which is a measure of responsiveness in the residential sector, tends to be around -.4 to -.6,” he said. “What that means is if you raise your prices by 1% you can expect to see on average a reduction in demand of about .4 to .6%, but it’s highly dependent on local conditions. I’ve seen anything from .2 up to .9, but this is a central tendency, and it’s similar to price responsiveness for other types of utilities, like electricity as well.”

One advantage of using pricing is that if you have metered customers, you have a monitoring system already in place, Mr. Baerenklau said. “But the down side of pricing is that there’s a fair amount of evidence in the literature that pricing tends to be regressive, and what that means is that it has a disproportionate impact at lower income households and most of us might think that that’s unfair. So there are upsides and downsides to pricing, but there are ways we can deal with that regressiveness of pricing policies.”

Mr. Baerenklau said that U.C. Riverside recently did a study for Eastern Municipal Water District, who switched from uniform rates to budget-based rates in 2009. The water district had experienced a drop in demand, but didn’t know how much was due to the rate structure. “We built a water demand model under uniform rates, and we used it to predict what demand would have been in Eastern’s service area if they had stuck with their uniform rates instead of switching to the budget based rates, but if they had set the price per unit equal to the same average price that people actually paid under those budget rates,” he said. “We controlled for the average price level, and we looked to see what difference do we think there was in demand. The graph on the left shows you what we saw, broken out by three different customer classes defined by different efficiency levels.”

Mr. Baerenklau said that U.C. Riverside recently did a study for Eastern Municipal Water District, who switched from uniform rates to budget-based rates in 2009. The water district had experienced a drop in demand, but didn’t know how much was due to the rate structure. “We built a water demand model under uniform rates, and we used it to predict what demand would have been in Eastern’s service area if they had stuck with their uniform rates instead of switching to the budget based rates, but if they had set the price per unit equal to the same average price that people actually paid under those budget rates,” he said. “We controlled for the average price level, and we looked to see what difference do we think there was in demand. The graph on the left shows you what we saw, broken out by three different customer classes defined by different efficiency levels.”

The main message here is that we think they are achieving a 10 to 15% reduction in demand than with the previous uniform rate structure, he said. “The more interesting story is that it’s the most inefficient users that have really responded the most to that rate structure change,” he said. “The red line shows that the most inefficient third of households are now about 25 to 30% below where we think they would have been on that equivalent uniform rate structure.”

He then presented another graph that demonstrates the same sort of response. “Before the introduction of the rate structure, the efficient households on the top were spending about 11 and half months of each year within budget; the inefficient households were only spending about 3.4 months per year within budget. After the rate structure was put in place, the efficient households effectively had very little change in their behavior, but it is the inefficient households who are now spending 8.5 months per year within their budget, so it really did impinge most upon the most inefficient users.”

He then presented another graph that demonstrates the same sort of response. “Before the introduction of the rate structure, the efficient households on the top were spending about 11 and half months of each year within budget; the inefficient households were only spending about 3.4 months per year within budget. After the rate structure was put in place, the efficient households effectively had very little change in their behavior, but it is the inefficient households who are now spending 8.5 months per year within their budget, so it really did impinge most upon the most inefficient users.”

“Without going into all the details, we can also see that it really didn’t have much of an effect on, not only the behavior of the more efficient households, but on the low income households as well,” he added.

Programs

Mr. Baerenklau then turned to water conservation programs, saying there are three main conclusions can be drawn from the literature:

“First is that conservation practices often do not live up to expectations,” he said. “A lot of that is because of incorrect assumptions about customer behavior and how they are going to respond to these programs when they are put in place.”

“Second, there’s also evidence that these efficiency gains that we do observe vary significantly across cases, for all the same reasons that pricing elasticity is going to vary in different conditions: socio-economic status, season, pricing level, what other conservation programs you might have in place, and all kinds of things like that,” he said. “Efficiency gained from conservation programs are also going to vary, so you have to keep that in mind when implementing these programs.”

“The third is that conservation programs typically are not as cost-effective as pricing,” he said. “Part of the reason is that you have to somehow fund them, you probably have to monitor what’s going on, and there’s also a lot of evidence that you are paying people to do things that they probably would do otherwise. There was a study that was done on low flow toilets, and the estimate after they figured out how many people would have installed low flow toilets without the rebate was that the rebate really only generated 33% of the actual water savings. In two-thirds of the cases, the people were going to install these things anyway but were glad they received the rebate.”

“So the lesson here is that for a lot of us, conservation is not driven by the financial side, it’s attitudinal,” he said. “If you understand the attitudes of your customers and you understand their propensities, you can lean on other levers to bring about that behavior without having to pay them to do it, so that program was effectively three times more expensive that it really needed to be if they were able to effectively target those rebates for whom the rebate would have changed their behavior.”

“I’m not saying we need to go without conservation programs, far from it,” he said. “One of the big benefits is that these conservation programs can really help the address the equity issues I talked about regarding pricing. If you have a rate structure place that it has some regressive elements to it, you can actually counteract that effect with properly designed and properly targeted conservation programs.”

Mr. Baerenklau then turned to some recent developments on conservation programs. He first presented a graph from a study with Western Municipal Water District regarding their free sprinkler nozzles program. “What you see here is a treatment-effect, as though we had done an experiment,” he explained. He noted that the people who did not get a voucher were on the left, and those that did are on the right. “With the no voucher sample we saw an increase in 8% from 2010 to 2012, and for the voucher sample, we saw a decrease of close to 1%. Looking at the difference between those two, there was a 9% overall difference in consumption between the treatment and the control group, so it looks like they are achieving about a 9% reduction in demand. That’s a summertime reduction by the way, due to the sprinkler heads.”

Mr. Baerenklau then turned to some recent developments on conservation programs. He first presented a graph from a study with Western Municipal Water District regarding their free sprinkler nozzles program. “What you see here is a treatment-effect, as though we had done an experiment,” he explained. He noted that the people who did not get a voucher were on the left, and those that did are on the right. “With the no voucher sample we saw an increase in 8% from 2010 to 2012, and for the voucher sample, we saw a decrease of close to 1%. Looking at the difference between those two, there was a 9% overall difference in consumption between the treatment and the control group, so it looks like they are achieving about a 9% reduction in demand. That’s a summertime reduction by the way, due to the sprinkler heads.”

“The interesting thing about this is that the sprinkler head are able to achieve 30% reduction under the testing conditions and we’re only getting a little bit less than a third of that in practice,” he said. “We don’t yet know why and we don’t actually have a monitoring plan in place to understand who installed them and if they did it the right way. Maybe they just took them home and set them in the garage and forgot about them.”

He noted that there is a second model which takes a different approach and gives and estimate in about the same range. “It’s a good example of how testing conditions and implementation conditions will give you very different results, largely due to customer behavior and customer responses,” he said.

Mr. Baerenklau then turned to lawn and turf replacement programs, presenting the results from a recent summary published by professional agronomist Sylvan Addink that summarized various turf replacement programs. He pointed out the bottom line per acre-foot cost, with El Paso being the standout. “In El Paso, this author estimated that their cost per acre foot through the turf replacement program was over $1800 to achieve these savings, and the thing that is different about that one program compared to all the others is that that’s the only program that didn’t also require an irrigation system upgrade,” he said.

Mr. Baerenklau then turned to lawn and turf replacement programs, presenting the results from a recent summary published by professional agronomist Sylvan Addink that summarized various turf replacement programs. He pointed out the bottom line per acre-foot cost, with El Paso being the standout. “In El Paso, this author estimated that their cost per acre foot through the turf replacement program was over $1800 to achieve these savings, and the thing that is different about that one program compared to all the others is that that’s the only program that didn’t also require an irrigation system upgrade,” he said.

There are other cases in literature that also document that the landscape is only giving you a fraction of the savings, he said. “The change in the landscape might get you a third of the savings, but it is the changes in the irrigation system that gives you the lion’s share of it. And that again has to do with customer behavior. They put in this new landscape and they continue watering it the way that they used to.”

They have documented cases where customers didn’t like how the plants looked in the summer when they go dormant as they are supposed to, so they kept pouring water on them. “So they didn’t get nearly the savings that they were hoping for, or on the other hand, the cost per unit was much, much higher, so accounting for consumer behavior is very important.”

Pleading and prohibiting

“The literature basically tells us that voluntary requests have pretty small effects,” he said. A case study in Atlanta found that when they offered only technical advice to customers, they did not see any reduction; when they offered technical advice with a request to conserve water from the General Manager, they had a 2.7% reduction, he said. He noted that in the Eastern study, they found that when a request was made to reduce usage due to maintenance, it looked like it had a 5% effect, “but I would emphasize I think that’s a very short term effect and the intent was not to try and achieve a longer term reduction.”

“Mandatory restrictions on the other hand can be very effective if you can figure out a good way to enforce them, but enforcement is costly and behavior is very slippery,” he said. “There’s a good example in Australia where they went to two day a week restrictions on irrigation systems, and everybody picked up the hose and went out and started doing more hand watering, so they didn’t get a lot of bang for their buck out of that program.”

“Mandatory restrictions on the other hand can be very effective if you can figure out a good way to enforce them, but enforcement is costly and behavior is very slippery,” he said. “There’s a good example in Australia where they went to two day a week restrictions on irrigation systems, and everybody picked up the hose and went out and started doing more hand watering, so they didn’t get a lot of bang for their buck out of that program.”

Restrictions and mandatory requirements tend to be inefficient in economic terms and thus very costly to households, Mr. Baerenklau said. “The one study that I’ve been able to find that actually documents this – it’s mostly a theoretical claim but there is some documentation in the literature – is this comparison between the two day per week irrigation restriction schedule relative to a price-based approach that would achieve the same aggregate level of conservation,” he said. “The authors estimated that the welfare cost to households was about 25% of their average monthly bill. That’s a fairly significant additional cost associated with using mandatory restrictions that are paid as opposed to a more flexible price based approach.”

Pressuring and Plastering

“Peer pressure seems to work,” he said. “It looks like from a couple different case studies, again the Atlanta study, they went from technical advice, to technical advice with the GM letter, to technical advice with the GM letter with the social norm comparison and they got close to a 5% reduction, which is really close to what we have heard for the Water Smart software, so that’s a number to keep in mind if you’re thinking about doing social norm comparisons.”

Mr. Baerenklau then turned to plastering, or conservation messaging, noting that he had come across an interesting study that has not yet gone through peer review. “Two things,” he said. “Billing frequency doesn’t seem to have much of an effect on behavior. If you control for other features of the bill and you just bill bi-weekly, monthly or bi-monthly or whatever, there doesn’t seem to be much of an effect on behavior.”

Mr. Baerenklau then turned to plastering, or conservation messaging, noting that he had come across an interesting study that has not yet gone through peer review. “Two things,” he said. “Billing frequency doesn’t seem to have much of an effect on behavior. If you control for other features of the bill and you just bill bi-weekly, monthly or bi-monthly or whatever, there doesn’t seem to be much of an effect on behavior.”

“What they found with conservation messaging, though, and we’ll see whether or not it makes it through peer review, was really interesting,” he said. “They attempted to explain conservation effort for a city in Canada where they were looking at how many different things people tried to do in order to conserve water, and what they found was that one of the best predictors of that measure of effort was how many different sources of messages the customer could remember.”

Knowledge of water scarcity issues had no effect at all,” he pointed out. “As an educator, this is really depressing, but the message for you and the knowledge that you should take away from it is that maybe you should consider your messaging as more of PR and advertising. You want to be everywhere. You want to be like a brand, you want to be in front of everybody, wherever they look. Whether or not they know why they turned down the sprinkler system might not matter at all as long as they turned it down because that’s just the message they get exposed to everywhere. So this is a pretty interesting result; we’ll see whether and when it gets through the peer review process and what the results look like then, but nonetheless, something worth keeping in mind.”

Knowledge of water scarcity issues had no effect at all,” he pointed out. “As an educator, this is really depressing, but the message for you and the knowledge that you should take away from it is that maybe you should consider your messaging as more of PR and advertising. You want to be everywhere. You want to be like a brand, you want to be in front of everybody, wherever they look. Whether or not they know why they turned down the sprinkler system might not matter at all as long as they turned it down because that’s just the message they get exposed to everywhere. So this is a pretty interesting result; we’ll see whether and when it gets through the peer review process and what the results look like then, but nonetheless, something worth keeping in mind.”

So in conclusion …

“Understand your customers and try to target your policies,” said Mr. Baerenklau. “Speaking as an economist, do everything you can to put a robust rate structure at the core of your conservation strategy. If you get that part right, I think that is most of the battle.”

“Understand your customers and try to target your policies,” said Mr. Baerenklau. “Speaking as an economist, do everything you can to put a robust rate structure at the core of your conservation strategy. If you get that part right, I think that is most of the battle.”

“Everybody knows we did the study on budget based rates and that they have a lot to offer, but I also think the bigger point here is to do what works well for you in your situation; if it’s budget based rates, great, if it’s something else, great, but get this piece of the puzzle right,” he said. “Then around that core of your strategy, develop these complimentary conservation programs that can help tweak the overall outcome. If you have an inefficient price structure and you feel like you’re living with the price structure that you have and not the one you wish you had, go get the one you wish you had and then design things around it.”

“To the extent that you can, try to avoid constraining behavior,” he said. “Again, that gets back to the value that there is in flexibility in letting people choose what they want to do. My point about messaging, that it might be more about advertising and PR than about education and also that peer pressure seems to be cheap and effective, and then to complete the loop, once you’ve done all that, go back and look at the data again. Just like you need to dig in your data to understand your customers the first time, when you make these changes, dig back into it and see how things have changed. What did they do, what did you learn, and build that back into your overall strategy.”

Help fill up Maven’s glass!

Maven’s Notebook remains only half-funded for the year.