The Delta of our modern times bears little resemblance to its historical self, a mix of native and non-native species existing in an environment that has been long been sculpted to suit society’s purposes. Dr. Peter Moyle, Associate Director for UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences and professor with the Wildlife, Fish, and Conservation Biology Department, describes the resulting Delta ecosystem as ‘novel’, and in this presentation from the 2014 Bay Delta Science Conference, argues that these novel ecosystems can be fairly stable and resilient, as well as presumably manipulated to some degree to generate favorable outcomes.

He began by saying that most aquatic ecosystems in California are novel ecosystems. “They have a superficial resemblance to the historic systems,” he said. “They sort of look good, but they’re irreversibly altered, physically, and chemically. They are very different in many respects from the historic systems that were there, and they contain mixtures of native and alien species.”

He began by saying that most aquatic ecosystems in California are novel ecosystems. “They have a superficial resemblance to the historic systems,” he said. “They sort of look good, but they’re irreversibly altered, physically, and chemically. They are very different in many respects from the historic systems that were there, and they contain mixtures of native and alien species.”

He pointed out that most of our aquatic systems are more species-rich today than they were historically. “What we don’t know is how novel they are in structure and function,” he said. “My guess is that they pretty much function the same way, but with many new nuances of structure and function because of the species that make them up.”

“So the big question is are they novel in structure and function?” he said. “Because we have a lot more species and in unprecedented combinations—remember, we have fish and invertebrates, plants from all over the world, all living together in this estuary, unfortunately our historic ecosystems are rather limited as models for our modern, present-day ecosystems. They can only hint at the conditions in which the native fishes evolved. That’s important because if we want to protect our native fish, we have to recreate some of the historic conditions in which they evolved as much as we can, but in fact we can’t go back again. We are not going to go back anything even vaguely approaching our historic systems.”

“In fact, I think some of our baselines that we do use for restoration are actually really altered ecosystems,” Dr. Moyle pointed out. “After all, in the 19th century we had extraordinarily rapid change in our aquatic ecosystems before anybody was looking. Of course we have this wonderful document by SFEI on the historic Delta, and that gives you some template at least to work from and some idea of what the historic landscape was like, but we have to recognize that what we’re working with is very different today than what was there at that time.”

“In fact, I think some of our baselines that we do use for restoration are actually really altered ecosystems,” Dr. Moyle pointed out. “After all, in the 19th century we had extraordinarily rapid change in our aquatic ecosystems before anybody was looking. Of course we have this wonderful document by SFEI on the historic Delta, and that gives you some template at least to work from and some idea of what the historic landscape was like, but we have to recognize that what we’re working with is very different today than what was there at that time.”

“So why emphasize novel ecosystems?” said Dr. Moyle. “It’s the reality. It’s the way things are. We have systems that are unprecedented in structure and in species composition. Also, if we think in terms of novel ecosystems, maybe we’ll think of some novel approaches to conserving the native species or at least novel approaches to management. It means we don’t have to be stuck with our standard way of doing things.”

He said he would emphasize this point by talking about three novel ecosystems: the north Delta, the central Delta, and the Suisun Marsh, noting that this draws largely on the work of the UC Davis Ark project.

North Delta

The majority of individual fishes caught in the Cache Slough complex are non-native; less than 20% are natives, Dr. Moyle said. “The interesting thing is the number of native species is much higher and that means you have a lot to work with,” he said. “Just because something is in low abundance doesn’t mean that we can’t create environments that put them in higher abundance. But that tells you what a novel ecosystem is in part, because we have this dominance of non-native species. Even if you break it up with different sampling methods—sampling methods do give you a bias in terms of what species you get—you still get the same huge bias towards non-native species.”

The majority of individual fishes caught in the Cache Slough complex are non-native; less than 20% are natives, Dr. Moyle said. “The interesting thing is the number of native species is much higher and that means you have a lot to work with,” he said. “Just because something is in low abundance doesn’t mean that we can’t create environments that put them in higher abundance. But that tells you what a novel ecosystem is in part, because we have this dominance of non-native species. Even if you break it up with different sampling methods—sampling methods do give you a bias in terms of what species you get—you still get the same huge bias towards non-native species.”

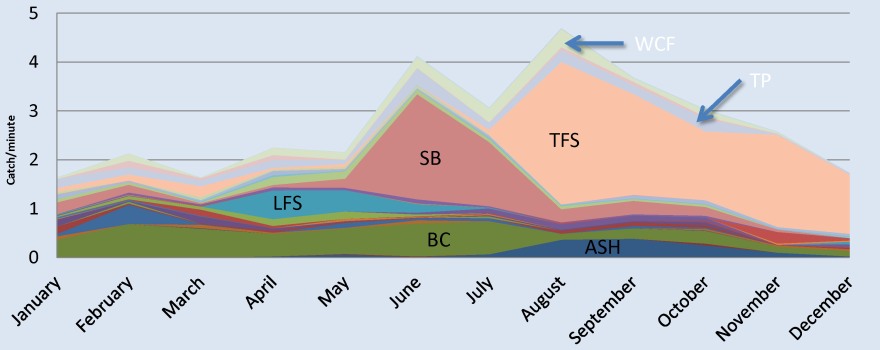

There are also shifts in seasonal abundance, he said, presenting a graph of abundance of young-of-year in Cache Slough. He pointed out that the abundance of species shifts through time. “There’s a lot of dynamic interactions among these species taking place, and dynamic interactions with the environment,” he said.

There are also shifts in seasonal abundance, he said, presenting a graph of abundance of young-of-year in Cache Slough. He pointed out that the abundance of species shifts through time. “There’s a lot of dynamic interactions among these species taking place, and dynamic interactions with the environment,” he said.

“Likewise when you go to different places in the system, you find different species occurring in different areas – for example, the upper end sloughs tend to support more striped bass and threadfin shad, while the lower ends of some of these sloughs are supporting more smelt and other critters. These things change with season and time, so they are very dynamic systems made up of native and non-native species that are very complex and often very hard to understand.”

“Likewise when you go to different places in the system, you find different species occurring in different areas – for example, the upper end sloughs tend to support more striped bass and threadfin shad, while the lower ends of some of these sloughs are supporting more smelt and other critters. These things change with season and time, so they are very dynamic systems made up of native and non-native species that are very complex and often very hard to understand.”

“It’s not just the fish; it’s also zooplankton,” he said, presenting a graph of zooplankton abundance. “The Sinocalanus, the Harpacticoid, the Limnoithona, Eurytemora, Pseudodiaptomus—they’re mostly non-native species. So the basis of the food webs—most of those species are non-native species, so we’re dealing with ecosystems that are at all levels a mixture of native and non-native species.”

“It’s not just the fish; it’s also zooplankton,” he said, presenting a graph of zooplankton abundance. “The Sinocalanus, the Harpacticoid, the Limnoithona, Eurytemora, Pseudodiaptomus—they’re mostly non-native species. So the basis of the food webs—most of those species are non-native species, so we’re dealing with ecosystems that are at all levels a mixture of native and non-native species.”

Central Delta

Dr. Moyle said that it is similar in the Central Delta. “This is about as altered an ecosystem as you can find,” he said. “It’s dominated by our so-called ecosystem engineers: Brazilian waterweed and overbite clam, which really change the whole nature of the systems in favor of another suite of non-native species.”

Dr. Moyle said that it is similar in the Central Delta. “This is about as altered an ecosystem as you can find,” he said. “It’s dominated by our so-called ecosystem engineers: Brazilian waterweed and overbite clam, which really change the whole nature of the systems in favor of another suite of non-native species.”

In terms of fish, there are very few native individual species caught, and about 20% of the types of species caught are native. “Again, obviously a system dominated by non-native species,” he said.

In terms of fish, there are very few native individual species caught, and about 20% of the types of species caught are native. “Again, obviously a system dominated by non-native species,” he said.

Suisun Marsh

He then turned to Suisun Marsh. “Suisun Marsh is right in the middle of the salinity gradient and right in the middle of the estuary, and that helps with the native fishes, because generally the saltier the environment is the more native fishes you have,” he said.

He then turned to Suisun Marsh. “Suisun Marsh is right in the middle of the salinity gradient and right in the middle of the estuary, and that helps with the native fishes, because generally the saltier the environment is the more native fishes you have,” he said.

“But Suisun Marsh is not a natural system by any stretch of the imagination. It’s a bunch of duck clubs, which are all intensely managed with a big wildlife area out there. It looks good, but it’s a very unnatural place in many respects. It’s highly managed, with many non-native plants and animals throughout. You can tell just by the fact that there are 370 kilometers of dikes in that system.”

“But Suisun Marsh is not a natural system by any stretch of the imagination. It’s a bunch of duck clubs, which are all intensely managed with a big wildlife area out there. It looks good, but it’s a very unnatural place in many respects. It’s highly managed, with many non-native plants and animals throughout. You can tell just by the fact that there are 370 kilometers of dikes in that system.”

Dr. Moyle said that there is some natural habitat here and it’s a bit salty, so about 35% of the individual fish we catch are natives, and about half of the types of species. “So there is more hope in Suisun Marsh for the native species but, again, it’s an interactive ecosystem; all these species are interacting with one another, natives and non-natives,” he said.

Dr. Moyle said that there is some natural habitat here and it’s a bit salty, so about 35% of the individual fish we catch are natives, and about half of the types of species. “So there is more hope in Suisun Marsh for the native species but, again, it’s an interactive ecosystem; all these species are interacting with one another, natives and non-natives,” he said.

He then presented a graph of the population of both native and non-native species through time, noting that purple is the natives and the striped portion is the non-natives. “They are going up and down together,” he noted. “By and large, there tend to be wider fluctuations in the non-native fish populations than in the native fish populations, but basically they’re responding to the environment in a similar fashion, with a lot of exceptions when you start drilling down into the details.” Dr. Moyle said that if one coming into the system fresh and just started to look at the fish might think that this is co-evolved system and that the fish that must have lived together for a long time, because they’re doing different things in different places.

He then presented a graph of the population of both native and non-native species through time, noting that purple is the natives and the striped portion is the non-natives. “They are going up and down together,” he noted. “By and large, there tend to be wider fluctuations in the non-native fish populations than in the native fish populations, but basically they’re responding to the environment in a similar fashion, with a lot of exceptions when you start drilling down into the details.” Dr. Moyle said that if one coming into the system fresh and just started to look at the fish might think that this is co-evolved system and that the fish that must have lived together for a long time, because they’re doing different things in different places.

He then presented a slide depicting the more common fishes in the marsh, noting that any picture with an “A” on it is an alien species. “The core group of fishes, top 10 or 20 species, varies in relative abundance in time and place in the marsh,” he said. “This is just one slough showing the dominant species through time, so a lot of changes taking place constantly, a very dynamic system, and yet it seems to work. That’s the amazing thing. And yet there are changes through time.”

He then presented a slide depicting the more common fishes in the marsh, noting that any picture with an “A” on it is an alien species. “The core group of fishes, top 10 or 20 species, varies in relative abundance in time and place in the marsh,” he said. “This is just one slough showing the dominant species through time, so a lot of changes taking place constantly, a very dynamic system, and yet it seems to work. That’s the amazing thing. And yet there are changes through time.”

He then presented a slide of the top 10 species from 1980-89 and from 2002-12. “You can see there’s been a shift in 2 species,” he said. “The longfin smelt and Sacramento sucker were among the 10 most abundant species when we started working up there; they are no longer in the top 10. They’ve been replaced by white catfish and black crappie, and this will change again. But on the other hand, you could argue most of these species are remarkably stable in terms of being in relative abundance through time. And again, it’s a mixture—the red’s non-native and the blacks are native species.”

He then presented a slide of the top 10 species from 1980-89 and from 2002-12. “You can see there’s been a shift in 2 species,” he said. “The longfin smelt and Sacramento sucker were among the 10 most abundant species when we started working up there; they are no longer in the top 10. They’ve been replaced by white catfish and black crappie, and this will change again. But on the other hand, you could argue most of these species are remarkably stable in terms of being in relative abundance through time. And again, it’s a mixture—the red’s non-native and the blacks are native species.”

And yet this is a system that is being constantly invaded, he said. “These are the macro-invaders that have occurred—the more spectacular ones, really since we’ve been working out there. Two species of goby, the Siberian prawn; of course, the overbite clam, and Maeotias jellyfish. And lots of other invasions, more micro-scale, have taken place at the same time.”

And yet this is a system that is being constantly invaded, he said. “These are the macro-invaders that have occurred—the more spectacular ones, really since we’ve been working out there. Two species of goby, the Siberian prawn; of course, the overbite clam, and Maeotias jellyfish. And lots of other invasions, more micro-scale, have taken place at the same time.”

“Likewise the zooplankton are largely non-native species,” he said. “There are lots of non-native invertebrates in these sloughs and in the diets of the fish. There is this whole association of native and non-native species in very complex food webs.”

“Likewise the zooplankton are largely non-native species,” he said. “There are lots of non-native invertebrates in these sloughs and in the diets of the fish. There is this whole association of native and non-native species in very complex food webs.”

Conclusions

“The Suisun Marsh and the Delta are novel ecosystems,” said Dr. Moyle. “They are unprecedented ecosystems; we’ve never seen anything like them before and we have to take that into account. Alien fishes and invertebrates dominate in most areas. They can look pretty good, but a lot of what you actually see out there when you’re sampling is a mixture of native and non-native species.”

“The Suisun Marsh and the Delta are novel ecosystems,” said Dr. Moyle. “They are unprecedented ecosystems; we’ve never seen anything like them before and we have to take that into account. Alien fishes and invertebrates dominate in most areas. They can look pretty good, but a lot of what you actually see out there when you’re sampling is a mixture of native and non-native species.”

“We also have to conclude that tidal marsh structure and function is highly variable and highly complex,” he said. “There’s a lot of dynamic things going on in the different sloughs and different parts of the estuary: the fish fauna, the zooplankton – everything seems like it’s constantly changing, so it’s really hard to get a good grasp on what’s going on. Yet, I’m convinced a lot of it’s fairly predictable too, especially predictable in relation to environmental variables.”

“Pelagic fishes are a big orientation of a lot of the research around here, and that pelagic tidal habitat is also highly altered,” he said. “The tidal cycles are different – the way tides move in and out of these diked sloughs, the plankton that’s out there—these are all new and all different from what they were historically and what the native fishes especially evolved in.”

“Pelagic fishes are a big orientation of a lot of the research around here, and that pelagic tidal habitat is also highly altered,” he said. “The tidal cycles are different – the way tides move in and out of these diked sloughs, the plankton that’s out there—these are all new and all different from what they were historically and what the native fishes especially evolved in.”

“It is worth noting that tidal marsh habitat benefits native fish most in Suisun Marsh,” he said. “It seems to be the place where tidal marshes work and I think there are a lot of things going on out there that we can learn from the marsh.”

Implications

The implications are that these novel assemblages are going to persist in all habitats in the estuary, he said. “We’re going to have to live with them, and they’re going to keep changing. Unfortunately we’re going to keep getting new species coming in; they just seem to appear magically,” he said.

“We have to figure out how to manage for desirable species, which means we have to define what desirable species are,” said Dr. Moyle. “Frankly, some of these desirable species are non-natives; striped bass for example, is probably a species which fits well in the estuary, it should be treated more or less the same as the natives.”

We also know that passive restoration of tidal marsh is not working, he said. “It’s unlikely to benefit native fishes, but especially pelagic species,” he said. “We’re going to have to really take charge. If we’re going to do what’s called restoration, we have to do it in a very positive way and really be willing to make our own major changes to the environment. The environment has changed so much; we have to figure out how to change it to something that we really want that will keep the fishes and the other critters around that we want. We have to really manipulate that environment.”

We also know that passive restoration of tidal marsh is not working, he said. “It’s unlikely to benefit native fishes, but especially pelagic species,” he said. “We’re going to have to really take charge. If we’re going to do what’s called restoration, we have to do it in a very positive way and really be willing to make our own major changes to the environment. The environment has changed so much; we have to figure out how to change it to something that we really want that will keep the fishes and the other critters around that we want. We have to really manipulate that environment.”

“Active management and monitoring of all restoration projects is really required for success,” he said. “I emphasize the monitoring as well: we really have to know what’s going on in these systems and actively manage the

“Active management and monitoring of all restoration projects is really required for success,” he said. “I emphasize the monitoring as well: we really have to know what’s going on in these systems and actively manage the

One of the places being managed is the Luco Pond in the Demberton Duck Club, he said. “The duck club is managing it in a way for ducks, but it turns out to be a very good way to manage it for fish. Basically, it’s being managed in a way so that it has tidal circulation. And it’s a great place for small fish and for larval fish. Right now, the fish that are in there are mostly non-natives, but we have a vision this could be a place you could manipulate for native fishes. You could throw splittail in there for example, and get them to spawn or even Delta smelt.”

One of the places being managed is the Luco Pond in the Demberton Duck Club, he said. “The duck club is managing it in a way for ducks, but it turns out to be a very good way to manage it for fish. Basically, it’s being managed in a way so that it has tidal circulation. And it’s a great place for small fish and for larval fish. Right now, the fish that are in there are mostly non-natives, but we have a vision this could be a place you could manipulate for native fishes. You could throw splittail in there for example, and get them to spawn or even Delta smelt.”

“We have to be thinking of building places like this, and literally I mean building, from in their present places in the marsh,” he said, presenting a slide of a design of Luco Pond showing an idea of how to build a functional pond.

“We have to be thinking of building places like this, and literally I mean building, from in their present places in the marsh,” he said, presenting a slide of a design of Luco Pond showing an idea of how to build a functional pond.

“This is a highly altered environment, and we have to work with it if we want to improve it for the desirable species,” said Dr. Moyle.

He concluded by acknowledging that the ideas presented were the result of the contributions of many ‘amazing’ people working in his lab, as well as those sponsors who helped fund the research.

Questions

Dr. Moyle was asked if this could be applied to San Pablo Bay. “Yes, certainly. In the more marine systems, you have a lot more native species, but the richness of invertebrates in the marine systems of San Francisco Bay is largely the result of non-native species, so truly the fishes seem to have done better in that regard – they are mostly natives. But truly in a place like San Pablo Bay or in the tidal marshes around San Pablo Bay we have the same kinds of issues. New ecosystems with new species interacting with one another in ways we don’t fully understand.”

Dr. Moyle was asked where the alien invaders come from. “They come from all over the world. Literally, a lot of the more recent ones are ballast water invaders coming in on ships. We have a lot of organisms here from Japan and China; the jellyfish are mostly from the Caspian Sea, so it’s literally fauna from all over the world. The fishes—it’s a mixture of fish; most of our fish, the non-native fish come from the eastern United States, so it’s a true eclectic mixture of organisms.”