The University of California’s Agriculture and Natural Resources (UCANR) has developed a series of webinars titled Insights: Water and Drought which feature timely, relevant expertise on water and drought from experts around the University of California system.

The University of California’s Agriculture and Natural Resources (UCANR) has developed a series of webinars titled Insights: Water and Drought which feature timely, relevant expertise on water and drought from experts around the University of California system.

Ellen Hanak is an economist and water policy specialist with the Public Policy Institute of California, a nonpartisan research organization that works on important public policy issues for the state. In this webinar, Ms. Hanak discusses the background, trends, and policy implications of water marketing and the related practice of groundwater banking. She noted that she would be presenting data from a study released in November of 2012, saying it was too soon in this drought to know how things are playing out.

“Water marketing refers to the temporary, long-term or permanent trades of the rights to use water,” began Ms. Hanak. “Groundwater banking refers to the storage of surface water underground in aquifers in the wet years, so that it’s available for use in dry years.” Groundwater banking can involve banking and storing for those using that particular aquifer, as well as for those who are offsite, she noted.

Water marketing and groundwater banking are tools that can reduce the cost of drought, said Ms. Hanak. A water market enables those with water use rights to forego their water use and instead make that water available to those who might need it in exchange for financial compensation. “The kinds of things you see are transfers between farmers who are growing annual crops like rice, cotton or corn to farmers who have tree crops that would be much more costly to not water because those trees could die. The compensation would involve making sure that the farmers who are scaling back on their crops will get enough money for not only covering their water costs but also any profits that they would have made from the growing of those crops and the use of water for that activity. There are also transfers to urban areas so that cities and suburbs don’t have to scale back on important activities during a drought, and also sometimes environmental transfers for the support of fish and wildlife.”

Water marketing and groundwater banking are tools that can reduce the cost of drought, said Ms. Hanak. A water market enables those with water use rights to forego their water use and instead make that water available to those who might need it in exchange for financial compensation. “The kinds of things you see are transfers between farmers who are growing annual crops like rice, cotton or corn to farmers who have tree crops that would be much more costly to not water because those trees could die. The compensation would involve making sure that the farmers who are scaling back on their crops will get enough money for not only covering their water costs but also any profits that they would have made from the growing of those crops and the use of water for that activity. There are also transfers to urban areas so that cities and suburbs don’t have to scale back on important activities during a drought, and also sometimes environmental transfers for the support of fish and wildlife.”

Water marketing can also help accommodate shifts in demand over the long term, she said. “If you’re getting changes in the geographic scale of economic activity, such as long-term shifts in demand for water in some places because of the rise of tree crops, you’d see some long-term shifts in demand there, as well as for population growth. This is also useful in the longer term in adapting to climate change, where we’re expecting that we’re going to be having more irregular and more frequent droughts probably combined with more frequent or more severe flooding, and the water market can help smooth that out with this compensation mechanism.”

Groundwater banking works similarly, she said. “It’s especially useful for storing water in wet years to have it available for dry years, but it’s also useful as part of a long-term tool for those folks who need more reliable water supplies.”

Both water marketing and groundwater banking have some requirements and some constraints. “A big requirement is infrastructure,” she said. “You need to be able to get the water from the seller to the buyer. Sometimes that can happen through a process of exchanges so it doesn’t have to be an exact draw, but you need to have the plumbing in place to be able to do that. With groundwater banking, you need to also be able to store, and retrieve the water from the banks. That will sometimes require some additional investments in infrastructure to be able to get the water to special recharge areas and perhaps some additional pumps to be able to get the water out again, and that might involve some new conveyance facilities as well.”

Both water marketing and groundwater banking have some requirements and some constraints. “A big requirement is infrastructure,” she said. “You need to be able to get the water from the seller to the buyer. Sometimes that can happen through a process of exchanges so it doesn’t have to be an exact draw, but you need to have the plumbing in place to be able to do that. With groundwater banking, you need to also be able to store, and retrieve the water from the banks. That will sometimes require some additional investments in infrastructure to be able to get the water to special recharge areas and perhaps some additional pumps to be able to get the water out again, and that might involve some new conveyance facilities as well.”

There are several institutional and legal rules that have to apply for this to work well, she said. “The first is that you shouldn’t be able to sell somebody else’s water, and that includes water for fish and wildlife and the environment. You shouldn’t be able to have impacts on other water users, and California law is pretty good at protecting other water users, especially other users of surface water. We’re not as good on the groundwater side because we don’t have a statewide law covering that, so counties have stepped in to provide some stopgap protections in that area.”

The second kind of protection applies to groundwater banking. “If I’m going to be storing water in a groundwater bank or in an aquifer somewhere, I need to be sure I can get it out in the same way as if I put money in a financial bank. With groundwater banking, it generally means you need a special set of management protocols and rules in order to do careful monitoring of who is putting water in and who is taking water out.” She noted that this works best in basins that are fully adjudicated where the rights to use water in a basin are parceled out and everybody knows exactly what shares they have, but it also works in some places that have semi-formal rules.

The third protection relates to others that could be affected and is especially relevant for water marketing. “If farmers are cutting back on their crops in order to sell water, that might have some economic impacts on the local farm community for the folks who aren’t able to sell as much in terms of inputs, for those who are not getting as many jobs working on the fields, and also downstream, less is going to the processing plants and transportation and all of the things that we think about as a crop sector. There’s often concern in the source communities about large-scale land fallowing, and transfers that involve a lot of fallowing often try to make sure that they are not having these kinds of negative economic impacts.”

It’s similar with groundwater banking, she said. “You want to make sure that you’re not having negative impacts on other folks in the surrounding area by the way the banking is operating. You don’t want to negatively impact their groundwater levels, which could mean more costly pumping for them.”

“California is unique among western states in having a very extensive infrastructure network with a lot of conveyance facilities and a lot of above and below ground opportunities for storage that facilitates water marketing and groundwater banking,” she said, presenting a map depicting water infrastructure across the state. She noted that the blue lines represent natural rivers, and the other colors represent the manmade aqueducts and canals used to move water around; the triangles represent reservoirs. “You get the sense that we’ve built a lot of conveyance infrastructure. This infrastructure basically makes it possible to move water from way up north at the top of the Sacramento River all the way down to San Diego. That happens through a process of exchanges and you lose some water over time through evaporation and so on, but basically it makes it possible to do quite a lot of marketing.”

“California is unique among western states in having a very extensive infrastructure network with a lot of conveyance facilities and a lot of above and below ground opportunities for storage that facilitates water marketing and groundwater banking,” she said, presenting a map depicting water infrastructure across the state. She noted that the blue lines represent natural rivers, and the other colors represent the manmade aqueducts and canals used to move water around; the triangles represent reservoirs. “You get the sense that we’ve built a lot of conveyance infrastructure. This infrastructure basically makes it possible to move water from way up north at the top of the Sacramento River all the way down to San Diego. That happens through a process of exchanges and you lose some water over time through evaporation and so on, but basically it makes it possible to do quite a lot of marketing.”

The map on the right depicts the counties that have been active in the market. “It’s basically the water users within those counties that have been active in the market and almost all of those, with the exception of the folks at the very top north in dark blue, have really been transfers that are not just within their county but actually within those regions, and in some cases, going across regions.”

The critical weakness in the state’s infrastructure for water marketing is the Delta, she said, noting that the Delta is circled in red on the map. “This is an area where we did not build conveyance but rely on pulling water from the Sacramento River through a series of manmade canals around manmade islands down to pumps that are down at the southwest of the Delta,” she said. “This was a decision made back when the State Water Project and the Central Valley Project were built because it was viewed as less expensive than building an artificial canal to bring the water through. It was recognized that eventually it might make sense to do something differently.”

The critical weakness in the state’s infrastructure for water marketing is the Delta, she said, noting that the Delta is circled in red on the map. “This is an area where we did not build conveyance but rely on pulling water from the Sacramento River through a series of manmade canals around manmade islands down to pumps that are down at the southwest of the Delta,” she said. “This was a decision made back when the State Water Project and the Central Valley Project were built because it was viewed as less expensive than building an artificial canal to bring the water through. It was recognized that eventually it might make sense to do something differently.”

There have been discussions about building tunnels underneath the Delta to get the water to the pumps, she said. “One of the reasons that folks are looking at that is to have more possibility of reliable service in various kinds of water years, and to be able to avoid some of the negative environmental impacts of pumping the way we’re doing it now,” she said. “This is a fragile hub in part because there are a lot of endangered fish species in this region and that makes it often very tricky in order to get the timing of moving the water in ways that are not harmful for the fish, and that are also useful for irrigators and urban users.”

“There’s a lot of earthquake risk in this area, so over the longer term, there’s concern about this system breaking down,” she said. “And because all of the areas that are not green in that picture – the yellow, the red and the orange – those are areas that are below sea level and so if an earthquake came and those islands were flooded, you would have salt water coming in from the ocean and from the Bay and that would force you to shut down the pumps as well.”

“In the near term, the big concerns are really related to the environmental constraints which have limited the ability to use the Delta, especially in dry years,” Ms. Hanak added.

The state doesn’t have protections that prevent people with groundwater wells to export that water to other places, she said. “People were concerned in the rural counties that this would lead to sucking the aquifer dry and putting it into the canal and sending it down to LA,” she said. “That was the concern back when a lot of the ordinances started to get put into place, especially in the late 90s. These are counties that don’t have a lot of groundwater regulation, but they were able to agree that they didn’t want people to be able to export groundwater.”

The state doesn’t have protections that prevent people with groundwater wells to export that water to other places, she said. “People were concerned in the rural counties that this would lead to sucking the aquifer dry and putting it into the canal and sending it down to LA,” she said. “That was the concern back when a lot of the ordinances started to get put into place, especially in the late 90s. These are counties that don’t have a lot of groundwater regulation, but they were able to agree that they didn’t want people to be able to export groundwater.”

She then presented a map showing the counties which have restrictions in place, noting that there are some differences between the restrictions. Counties represented in blue also restrict groundwater banking with parties outside of the county, while those in orange have restrictions that are limited to certain kinds of activities or that require people to get a permit for exporting groundwater, she said.

Water market trends

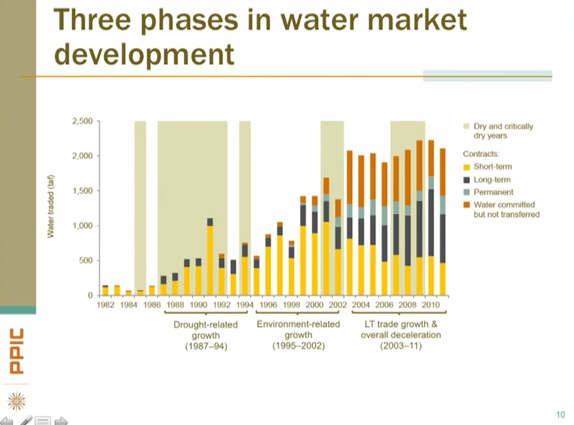

She then presented a graph of water transfers from the early 1980s through 2011. “Here’s the big picture overview,” she said. She noted that the background areas shaded beige were all dry and critically dry periods. “During this period of several decades, we’ve had some droughts, and that’s going to be instructive in thinking about the role of marketing during droughts.”

She then presented a graph of water transfers from the early 1980s through 2011. “Here’s the big picture overview,” she said. She noted that the background areas shaded beige were all dry and critically dry periods. “During this period of several decades, we’ve had some droughts, and that’s going to be instructive in thinking about the role of marketing during droughts.”

She explained that the bars show the total amount of water traded, with the yellow and blues indicating the amount of water that actually moved in any given year. The yellow portion of the bars are short-term transfers for a particular year. The dark blue portion indicates long term transfers, which are generally defined as a minimum of two years but are often for much longer, 10 to 12 years or more. The light blue indicates permanent transfers or permanent sales of water rights from one party to another. The orange indicates the maximum amount that could have been transferred but didn’t; in most cases this is because the deals are ramping up or other contract provisions. She noted that the market has picked up significantly since the early 90s.

Ms. Hanak said that the timeline can be broken into three phases:

Drought-related growth phase 1987-1994: In the early 80s, there wasn’t much of a water market; however, there were some drought years during this period which got the market going. “The numbers went from almost negligible to over a million acre-feet in 1991 which was the year of the launch of the state’s drought water bank,” she said. “California is quite famous for that around the world – it actually that was a way of avoiding serious rationing in 1991, and it got really experimental in a very short order of time.”

Environment-related growth phase 1995-2002: Most of these years were pretty wet, so the significant growth over this period of time is related to changes in environmental regulations. “This meant that some farmers had to buy water to make up water, because they lost water through new requirements on keeping water in streams, so they started buying water from other farmers. During this period, there was also the introduction of an environmental water market where the state and federal agencies were buying some water to support the environment.”

Long term trade growth & overall deceleration 2003-2011: There has been an overall deceleration in the pace of the market since 2003, but also a shift from short-term transfers to more long-term and permanent transfers. “That’s a combined shift that really reflects some changes, and arguably a maturation of the market, but also some new concerns.”

“Long term and permanent trades now dominate the market,” Ms. Hanak said, presenting a graph showing the overall breakdown of types of transfers in each of the three phases and noting that the short-term transfers are depicted in green and are now in the minority. “Most of the long term and permanent transactions have been purchases by cities, which now under 2001 law, need to show that they have long-term water available to support new development. We also see some of the higher value farms, especially in the San Joaquin Valley purchasing long-term contracts in order to know that they have water available for their tree crops. And there are a few long-term environmental transfers where there’s water purchased by state and/or federal agencies over anywhere from an 8 year to a 12 year contract to provide instream flows for the environment.”

“Long term and permanent trades now dominate the market,” Ms. Hanak said, presenting a graph showing the overall breakdown of types of transfers in each of the three phases and noting that the short-term transfers are depicted in green and are now in the minority. “Most of the long term and permanent transactions have been purchases by cities, which now under 2001 law, need to show that they have long-term water available to support new development. We also see some of the higher value farms, especially in the San Joaquin Valley purchasing long-term contracts in order to know that they have water available for their tree crops. And there are a few long-term environmental transfers where there’s water purchased by state and/or federal agencies over anywhere from an 8 year to a 12 year contract to provide instream flows for the environment.”

She then presented a graph of the 2003-2011 period. “It’s really pretty flat,” she said. “During the drought, we only made about half a million, maybe 600,000 acre-feet available in special dry year supplies between 2007 and 2010. And 2010 was still officially part of the drought, even though the year was not officially dry, and this is despite the fact that the state was hoping to really mobilize a lot of water through the water market, especially in 2009.”

She then presented a graph of the 2003-2011 period. “It’s really pretty flat,” she said. “During the drought, we only made about half a million, maybe 600,000 acre-feet available in special dry year supplies between 2007 and 2010. And 2010 was still officially part of the drought, even though the year was not officially dry, and this is despite the fact that the state was hoping to really mobilize a lot of water through the water market, especially in 2009.”

Ms. Hanak said there are a number of factors why the market was disappointing compared to the projections. “One was infrastructure constraints where new pumping restrictions on the Delta made it much harder to get water through from the northern part of the state to the San Joaquin Valley and the urban areas in the Bay Area and Southern California,” she said. “The second is institutional constraints, where it’s become a lot more difficult and more complex to get your transfers approved then it used to be.”

“When we started the drought water bank in 1991, that was put together in a matter of six weeks. There were some mistakes made in the process that were handled afterwards,” she said. “But arguably at this point, we’ve become much more risk averse to approving transfers during droughts than we were back in the early 90s. So, this is really something that a lot of people looked at after 2009 and did a lot of thinking about what do we need to do differently to make this work better.”

She then presented a graph that broke down the transfers by geographic region. She noted that in the early years, there were a lot of transfers going from the Sacramento Valley, but that has been significantly reduced in recent years. “It’s about one-third as much going out during the early drought period,” she said. “The San Joaquin Valley, which we normally think of as a net importer, has become a net exporter of water. This is especially in long-term and permanent sales of agricultural water contracts to urban areas in Southern California. SoCal has continued to be a net importer, much bigger now, and that’s really to support urban growth. The Bay Area is a relatively smaller player on the market, but also somewhat of a net importer.”

She then presented a graph that broke down the transfers by geographic region. She noted that in the early years, there were a lot of transfers going from the Sacramento Valley, but that has been significantly reduced in recent years. “It’s about one-third as much going out during the early drought period,” she said. “The San Joaquin Valley, which we normally think of as a net importer, has become a net exporter of water. This is especially in long-term and permanent sales of agricultural water contracts to urban areas in Southern California. SoCal has continued to be a net importer, much bigger now, and that’s really to support urban growth. The Bay Area is a relatively smaller player on the market, but also somewhat of a net importer.”

There is a lot more activity within counties and regions as the market has grown, she noted. “Overall, we’re moving about 1.5 MAF a year, and there are commitments to transfer up to 2 MAF,” she said. “In terms of the overall water use in CA, that is anywhere between 3 to 5% in a given year.”

Ms. Hanak then presented a graph of the breakdown of environmental water purchases throughout the years. “Environmental water purchases became something important, especially in that middle period between 95 and 2002,” she said. “It was really pretty significant, so in this middle period we were looking at almost half a million acre-feet of environmental water being purchased.” She noted that the orange indicates water going to wildlife refuges, the blue indicates water for San Joaquin River flows, and dark green was the Environmental Water Account, which was designed to basically help manage environmental flows while still making water available for other users. The smaller categories are environmental transfers in some localized regions, such as the Salton Sea and other river basins, she said.

Ms. Hanak then presented a graph of the breakdown of environmental water purchases throughout the years. “Environmental water purchases became something important, especially in that middle period between 95 and 2002,” she said. “It was really pretty significant, so in this middle period we were looking at almost half a million acre-feet of environmental water being purchased.” She noted that the orange indicates water going to wildlife refuges, the blue indicates water for San Joaquin River flows, and dark green was the Environmental Water Account, which was designed to basically help manage environmental flows while still making water available for other users. The smaller categories are environmental transfers in some localized regions, such as the Salton Sea and other river basins, she said.

“Environmental water purchases are a useful complement to environmental regulation because they can help lessen conflicts and they can also raise the efficiency of environmental water management, but you need a funding source for this, and the cash is running out,” she said, noting that this is a big part of why volume has been declining. “A lot of this money has been coming from taxpayer dollars and from state bonds in particular – about half was from state bonds. About a quarter of this money is coming from water users from a surcharge on water use in some specific projects.”

Groundwater banking trends

Ms. Hanak then gave an overview of groundwater banking trends. There are three types of groundwater banking, she said:

Formal: These are adjudicated basins or special management districts that have special legislative authority and the authority to monitor, account for pumping, and recharge, and to charge money for that. “You see that especially in SoCal and the Silicon Valley and the urbanized areas where problems have becomes so acute that people needed a management solution,” she said.

Informal management: This applies to most of the state where there is voluntary management; sometimes irrigation districts use price incentives to encourage people to use surface water and not to pump groundwater in wet years and that allows the groundwater basin to recharge. But they don’t really account for this in a very formal way, so it’s just for the overlying users, she said.

Semi-formal: This is where there parties to the groundwater bank outside of the area, and there is accounting of the water, such as in Kern County.

“The focus of our study was looking at banking that exists where offsite parties are storing their water, and this is especially in Kern County and in Southern California,” she said.

“First, I’ll show you where things are,” she said, presenting a map of California, noting that the blue indicates the groundwater basins are; the red are the adjudicated basins, and the yellow are special management districts, such as Orange County, the Coachella Valley and the Silicon Valley.

“First, I’ll show you where things are,” she said, presenting a map of California, noting that the blue indicates the groundwater basins are; the red are the adjudicated basins, and the yellow are special management districts, such as Orange County, the Coachella Valley and the Silicon Valley.

She then presented a slide of Kern County, noting that the colored areas depict the groundwater banks. “Many banks do banking, not only for members but for off-site parties, and they do that as part of a business operation where they are basically acting like a banker and they get a banker’s fee for that.”

She then presented a slide of Kern County, noting that the colored areas depict the groundwater banks. “Many banks do banking, not only for members but for off-site parties, and they do that as part of a business operation where they are basically acting like a banker and they get a banker’s fee for that.”

She next presented a slide depicting the amount of water stored in groundwater banks, noting that the orange indicates water stored in Kern County and the dark green groundwater storage done by Metropolitan Water District within their service area and other management areas.

She next presented a slide depicting the amount of water stored in groundwater banks, noting that the orange indicates water stored in Kern County and the dark green groundwater storage done by Metropolitan Water District within their service area and other management areas.

She noted that the storage levels were climbing, and then flattened out during the dry years in the early 2000s, and then began climbing again. “During the drought from 2007-09, and we see that the levels are going way down, and then back up again,” she said, noting that 2011 was a really wet year, so they were able to storage levels back to pre-drought levels.

“If you add up the amount that they took out in each year during this drought, we find it’s nearly 2 MAF, 1.9 MAF, and that’s three times more than what the water market made available in special dry year supplies, so this has been an extremely valuable tool during that most recent drought,” she said. “They were able to rapidly recharge and that was lucky, thanks to a big wet year where there were no constraints on Delta pumping and so a lot of water could come down and go into those banks.”

“But you did also see some conflicts arising in Kern County over the falling groundwater tables and concerns about whether the banks were causing some injury to local groundwater pumpers,” she noted.

Implications for policy

“So what does this mean in the context of the current drought?” Ms. Hanak said. “First of all, it’s been so dry this year, there were some real concerns about whether there was going to be much of a water market anyway. The Governor’s emergency declaration from back in January definitely did emphasize the idea of expediting water transfers as an important action, but until people knew what the water year was going to be like, there was a lot of reticence for folks potential sellers; they weren’t sure whether they were going to have water to be able to sell. Now that we did get some rains, you’ve seen some transfer arrangements happening and a lot of effort to try to make that happen more quickly. You definitely have also seen groundwater banks activated but we’re also seeing some of the constraints come into play as well.”

Ms. Hanak then highlighted the conclusions from the 2012 study, which are still relevant:

Address infrastructure gaps: This includes the Delta, but also there are some other smaller scale solutions to improve conveyance, the flexibility of the system, and the ability for people to use facilities differently that could help, she said. “We’re seeing this with DWR and USBR making it possible to use existing conveyance facilities for water we wouldn’t normally put in there, like allowing people to put groundwater in there from within the San Joaquin Valley to move it to other parts of the region.”

Make the institutional review proves more consistent, transparent and predictable: “I think there is some progress happening here, but there’s still a feeling that a lot more could be done to make this something that we can get going quickly in an emergency, as well as for longterm transfers that really need to be thought out well in advance.”

Strengthening local groundwater management: “This is a key thing, both for facilitating water marketing and especially for groundwater banking because if you don’t have a strong management system locally, you basically can’t do the accounting that you need to to run a bank.”

Developing models to mitigate local economic impacts: “This is a concern in the source regions, and there are some good models that are being tried in SoCal on the Colorado River system where there are some large scale fallowing operations underway to make water available for urban areas in Southern California. Part of that deal has involved putting together a fund in order to help support local economic development and mitigate harmful impacts.”

Engage high-level leaders who can take needed risks and break through barriers: “These are all the kinds of things that are not going to happen unless there’s the attention of people from the top, both at the state and at the federal level. Where we’ve seen big breakthroughs in our water market and in water banking have often been thanks to folks at the top making it possible for things to happen. A lot of the innovation will happen at the local level, but the locals need the rules to be set up in a way that they are not restricted overly by the rules.”

She pointed out that the current drought is focusing attention on addressing key gaps: “I think we are seeing some streamlining in the institutional review process, which is good. I think that’s going to have to be a continued conversation going on to next year and beyond, even if we’re not in dry times.”

Another area of progress is in local groundwater management. “There’s a lot of attention by both the administration and really grass roots efforts on the part of water agencies to think about how to improve the options for groundwater management at the local level in the places outside of urbanized areas that already have formal management systems,” she said. “We have a lot of overdraft in many of these areas now. We’ve basically used too much water in the normal years and don’t store enough in the wet times, and that’s leading us to find that in the dry times, when we’d like to have more groundwater available, we don’t, and so I think this is a really bright spot, maybe a silver lining of this drought.”

For more information …

- For more on water marketing, read the PPIC report: California’s Water Market, By the Numbers, Update 2012

- For more presentations from UCANR’s Water and Drought series posted on Maven’s Notebook, click here.

- To watch this webinar, click here.

- To view all the webinars in the series, Insights: Water and Drought, click here.

Coming up on Wednesday …

- Ellen Hanak, author Robert Glennon and others discuss water marketing at Stanford’s New Directions for U.S. Water Policy conference.

Help Maven fill the funding gap and keep unique content like this flowing …

Help Maven fill the funding gap and keep unique content like this flowing …

Make a tax-deductible donation or “join the club” today!