As the exceptionally dry conditions continue, the Governor and agency officials plead for water users to conserve, and water agencies across the state have responded by rolling out an array of water conservation programs in order to encourage consumers to use less water. But just how effective are these programs? Kurt Schwabe, Associate Professor of Environmental Economics and Policy at UC California, discussed the effectiveness of water conservation programs at the San Gabriel Valley Water Forum, held October 2nd in Pomona.

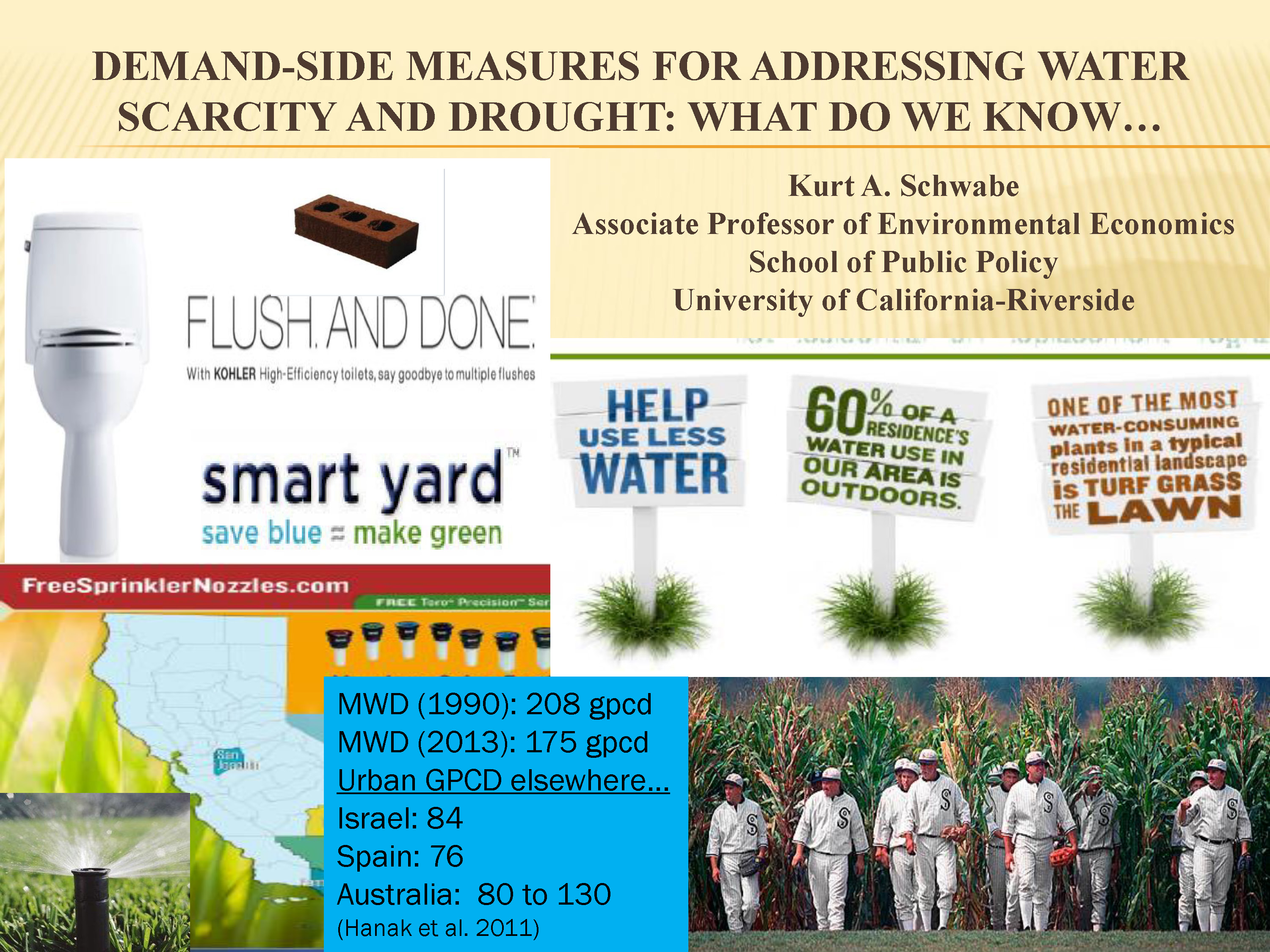

Kurt Schwabe began by presenting a slide depicting a multitude of various conservation programs being implemented by water agencies. “I think a nice adjective for it is ‘busy,’ and I think that would characterize a lot of water agencies efforts these days in addressing residential water demand and looking for ways to reduce it,” he said. “There’s turf grass removal, irrigation controllers, low flush toilets, low flow showerheads, and sprinkler efficiency programs, and because of that, the success of those programs can be seen in the reduction in per capita water use in the Metropolitan service area from around 280 gallons per capita per day in 1990 down to 175 gallons per capita per day in 2013. Consequently, while population has increased around 26% in the region, overall water use has only increased by 5%, so that’s good.”

Kurt Schwabe began by presenting a slide depicting a multitude of various conservation programs being implemented by water agencies. “I think a nice adjective for it is ‘busy,’ and I think that would characterize a lot of water agencies efforts these days in addressing residential water demand and looking for ways to reduce it,” he said. “There’s turf grass removal, irrigation controllers, low flush toilets, low flow showerheads, and sprinkler efficiency programs, and because of that, the success of those programs can be seen in the reduction in per capita water use in the Metropolitan service area from around 280 gallons per capita per day in 1990 down to 175 gallons per capita per day in 2013. Consequently, while population has increased around 26% in the region, overall water use has only increased by 5%, so that’s good.”

He recalled the story line in the picture, “Field of Dreams” and said that he thinks about this in terms of conservation. “If you provide these programs, will people use them, and will they use them correctly?” he said. “I’m going to suggest through this talk that we’re really not sure. There’s a lot to be gained in that, because there hasn’t been a lot of effort in the behavioral side of understanding water use.”

“To illustrate that, I’ve had this high efficiency sprinkler nozzle in my drawer for about a year and a half. I do take short showers, I feel guilty about this,” he said. “Secondly, I was listening to a home improvement show last year and a person calls up and says, ‘I’m not sure why people say putting a brick in your toilet helps with water conservation. It just seems to get everything clogged.’ They were putting it in the bowl and not the tank.”

Human behavior is important to understand if you want to continue making gains in reducing water use per capita, as has been seen in other countries. “We have to understand which programs work and which don’t and not just throw them all up on a website, and we need to do some program evaluation of that,” he said. “My objective for today’s talk is to highlight recent findings from studies in water conservation, and, I’m going to compare price-based approaches versus non-price-based approaches, and look at the effectiveness of non-priced based approaches. I’m going to hopefully persuade you that we know very little about the effectiveness of any particular program and through that, highlight the need for more systematic program evaluation to move forward effectively as well as cost-effectively.”

He said that there are two approaches to demand management:

- Price-based approaches, basically volumetric pricing, where prices are used to alter behavior; water use must be metered in this case.

- Non-priced based approaches alter behavior directly and indirectly. Technological adoption is one non price program, although it’s often coupled with rebates; research on that suggests most people adopt these technologies not for cost reasons but for environmental attitudes, although that can change, obviously, with the incentives that are offered, he said. Other non-priced approaches include rationing, school programs, flyers, moral suasion (such as the sign on I-5 “Serious drought, help save water”), and more recently, social norm messaging.

So how do price-based approaches compare with other approaches? Mr. Schwabe reviewed the results of some recent studies:

- A study by Chris Timmons at Duke in 2003 compared mandatory low-flow appliance regulation versus modest water price increases using data from 13 groundwater dependent agencies in California. He found that prices are almost always more cost effective than technology standards.

- Brennan, et al, and co authors in 2007 studied sprinkler restrictions in Perth, Australia, and she found that restrictions on use of sprinklers leads to more overwatering from hand held hoses, resulting from little water savings, but additional costs.

- A study by Grafton and Ward, also from Australia, in 2008, compared the effectiveness of mandatory restrictions to water prices in Sydney, and they found that mandatory water restrictions result in costly and inefficient responses relative to prices.

- A recent study by Mr. Schwabe and his associates Ken Bearenklau and Ariel Dinar at the University of California Riverside looked at Eastern Municipal Water District’s switch over to budget based tiered water rates and found that in a revenue-neutral perspective that water use was reduced between 10 and 15%.

So how effective are the technology-based rebate programs? “A study by Olmstead and Stavins emphasized the point that water savings for rebate programs are often smaller than initially supposed,” he said. “It’s most likely due to the ‘rebound effect,’ and I think we all engage in it. Some examples of that are that low flow showerheads result in longer showers, low flow toilets result in more flushing, and front load clothes washers result in more cycles, which my mom has confessed to me that she does. She’ll take the cold water and dump it on her plants until it gets hot, but she still does use that extra rinse cycle.”

Studies of the effectiveness of households fit with low-flow fixtures get mixed results. Some studies show that low-flow toilets save anywhere from 6 to 10 gallons per capita per day and other studies show none; low-flow showerheads save from 0 to 9%. “Engineering estimates are one thing, but you have to understand behavior to really understand how well these strategies are going to work,” he said.

Additionality is an important concept when considering cost effectiveness, Mr. Schwabe said. Additionality is a notional measurement of an intervention (or doing something) compared to the status quo (or doing nothing). Additionality becomes an issue when people adopt a technology and receive a rebate when they were likely to have adopted the technology anyway; in that instance, the claimed intervention is not truly additional since it would have been done anyway. “Target doesn’t give you all $50 gift certificates to go to Target; it only gives to the ones it doesn’t think are going to go there,” he said. “The same idea holds with the cost effectiveness of rebate programs.”

A study by Bennear and Taylor in 2013 looked at Northern Carolina rebate program for low-flush toilets and addressed the question of if the rebate program increased the number of households using low flush toilets and if it was cost effective. “They used agency household level information as well as their own survey about toilet replacement, and the result was they found that water savings from the toilet program let to approximately a water savings around 7%,” he said. “But only 33% of those savings was attributed to the program; the other 67% said they were going to do the program anyway.”

“Now you may not believe them or you may believe them,” Mr. Schwabe said. “It probably increased the timing in which they did it, but it’s an issue. Because of that, the program costs between $11 and $15 per thousand gallons saved. At the current time, they had other programs could achieve $7 per thousand gallons so they considered it not cost effective, but if they knew something more about their users, that is if they only targeted people that would have required the rebates, it would have become a very cost effective program at $4 per thousand gallons.”

Social norm messaging is one of the strategies that’s getting a lot of attention these days, he said. “This is the idea that you send your customers a message about their water use relative to their neighbors with neighbors being broadly defined as people who have similar characteristics, income, etc. as you do.”

“An excellent study done by Mitchell and Chestnutt that came out this last year that looked at EBMUD’s pilot of the WaterSmart home reports, and they found a 5.6% reduction on average at the end of one year pilot study, relative to the control group that didn’t receive the reports,” he said. “Now, they give them these reports every month and that’s important to keep in mind. They find a greater response by higher water users with no boomerang effect. The boomerang effect is that I get this report, and find that I’m under my neighbors so I increase my water use, but they find that didn’t happen in their analysis. They also found that people who had these home reports seemed to engage in other programs, so there’s some complementaries between the programs that I think is underappreciated in terms of these analyses.”

A second study by Ferraro sampled 100,000 households in Atlanta using a control group and three treatments: one group just received technical advice on saving water; one group received same technical advice but also a message from the general manager appealing to them to save water, and the third group received the technical advice but also the social norm comparison. “They find that the technology measure didn’t change water use at all, but the social messaging, the month after it was given, reduced water use by about 5%,” he said. “They had a greater response from high end water users, and also a greater response by high income water users, which is important, because high income water users are more price inelastic when it comes to water use.”

“Unfortunately, they found some waning effect. After four months, it was a 30% reduction in those savings, and after a year there was a 50% reduction, but the good news is that 50% stayed constant over four to six years,” he said. “And if they would have only focused on those that used above the median water user, they would achieve 88% of the savings at 66% of the costs.”

What about the effectiveness of turf grass removal programs? Mr. Schwabe said that the programs are popular during the drought and noted that Metropolitan has doubled its rebate for turf grass removal from $1 to $2 per square foot. “The question is how much can replacing grass with more drought tolerant plants help,” he said. “There’s a study at UCI done by Addink in 2014 where she reviewed case studies around the southwest. One case study was North Marin Water District in 1989. There were only 46 households that participated in the program and selectivity issues abound here, but still, they estimated that with changing the plants and the irrigation system resulted in 33 gallons per square foot saved.”

“In Albuquerque, a program that’s been in operation since 1996, once again through sprinkler replacement and changes in types of plants that are being grown, they found a 19 gallons per square foot saved, although 17% of the sample increased their water use. Once again, behavioral issues matter,” he said. “The Southern Nevada Water Authority looked at changing fescue with xeriscaping, and irrigation system improvements, and they estimated 62 gallons per square foot, but in El Paso, Texas, with 385 participants, they only estimated 18 gallons.”

The cost per acre foot saved ranged from $512 to $1800, but Mr. Schwabe said there were issues with all of these studies. For example, the El Paso case didn’t tie it to irrigation efficiency improvements. “The savings are mostly derived from improving irrigation efficiency,” he said. “Two thirds of the savings from improving irrigation and one-third from changing plant requirements is the conclusion of this paper. In Nevada, if they used the same landscape but improved the irrigation efficiency, they would have noticed a 30% reduction. Additionality raises its head here as well. In North Marin Water District, half of the participants were going to engage in the program already.”

There is a lack of comparison across different user groups, he said. “All the studies have focused on single family homes and really selective samples, so we have no idea how these things work for homeowner associations, apartments, and other groups. And the study concludes that people like their green grass, no surprise there. So the incentives you have to offer them for moving in that direction are going to have to be greater.”

“So in terms of some of the conclusions of those findings, we see that rebate conservation programs are attractive, but they fall short of initial estimates,” Mr. Schwabe said. “The cost effectiveness depends on behavioral issues, rebound and additionality issues, volumetric price based programs have been shown to be effective, and we have little idea on how to achieve successful programs nor how various programs interact.”

He then briefly discussed a study underway at University of California Riverside that is evaluating Eastern Municipal Water District’s high efficiency sprinkler nozzle program. “The two questions that we’re asking are, what factors are correlated with redeeming vouchers and, do those who redeem vouchers use less water relative to what they used before and, if so, by how much?,” he said, acknowledging that they don’t have information on whether they installed the sprinkler nozzles. “For just the interest of analysis, we looked at the people who redeemed the vouchers – did they behave differently, and what determines whether they redeem vouchers or not … the conclusion is that basically, socioeconomic and environmental differences across households seemed to explain decisions to redeem. Results might suggest that households redeeming vouchers reduced summertime water use somewhere between 3 and 9%. It really depends on our assumptions regarding what they do with the vouchers, and then we need more information to make accurate assessments.”

He then briefly discussed a study underway at University of California Riverside that is evaluating Eastern Municipal Water District’s high efficiency sprinkler nozzle program. “The two questions that we’re asking are, what factors are correlated with redeeming vouchers and, do those who redeem vouchers use less water relative to what they used before and, if so, by how much?,” he said, acknowledging that they don’t have information on whether they installed the sprinkler nozzles. “For just the interest of analysis, we looked at the people who redeemed the vouchers – did they behave differently, and what determines whether they redeem vouchers or not … the conclusion is that basically, socioeconomic and environmental differences across households seemed to explain decisions to redeem. Results might suggest that households redeeming vouchers reduced summertime water use somewhere between 3 and 9%. It really depends on our assumptions regarding what they do with the vouchers, and then we need more information to make accurate assessments.”

“So in conclusion, prices are both effective and cost-effective at reducing demand,” he said. “The structure and pricing likely matters but there’s not a lot of research that evaluates that. Cost effectiveness of many conservation programs depends on a number of factors, biophysical, socioeconomic, other programs that are being offered as well as the pricing types. I think the data exists and I see partnerships increasing to really identify which programs are going to be effective in take us well into reduced water use in the future. Thank you.”

For more information …

- You can view Kurt Schwabe’s presentation, as well as those of all the presenters, at the San Gabriel Valley Water Forum website here: Program Presentations