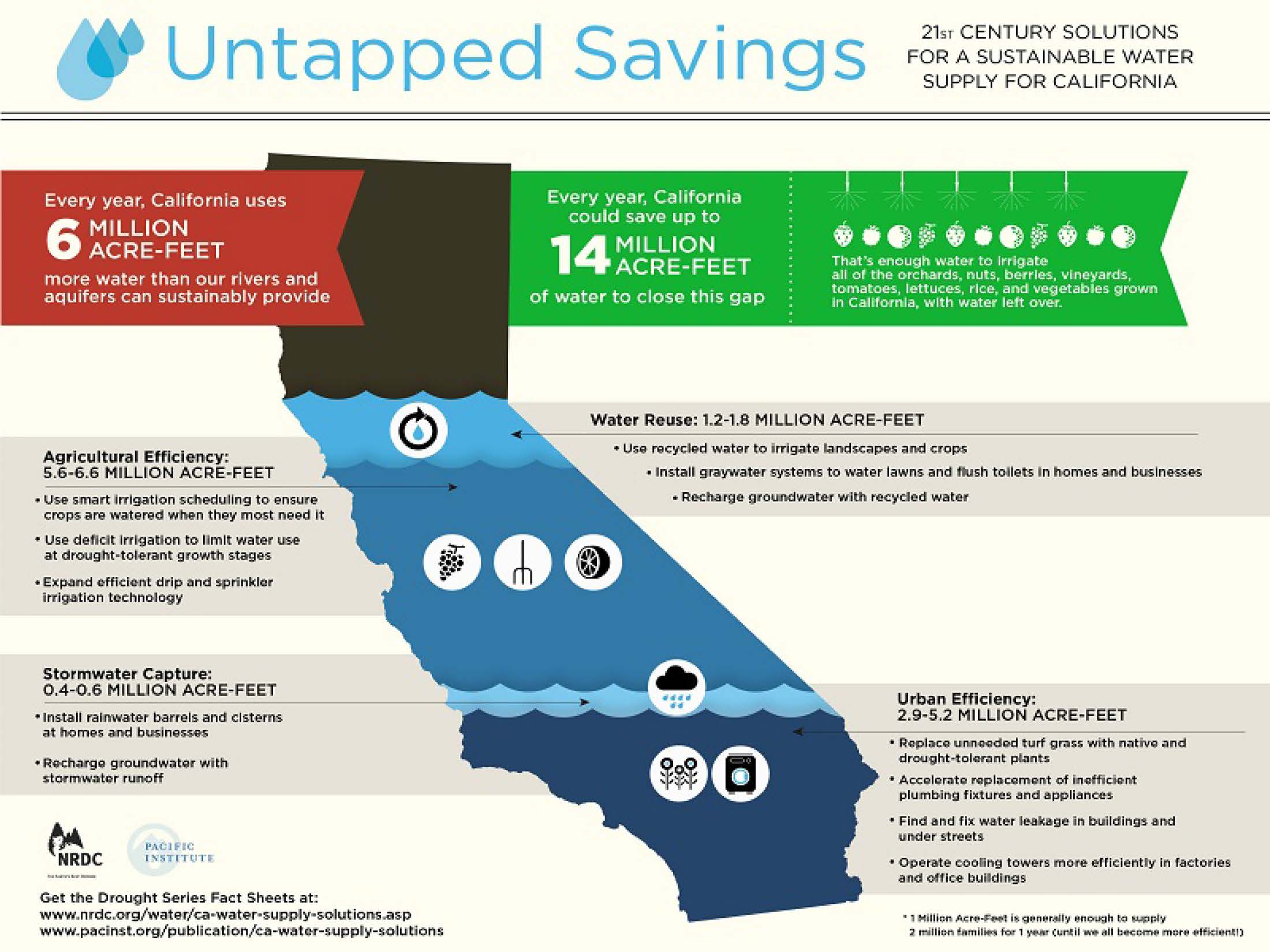

In June, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and Pacific Institute released a study that examined the potential water supply that can be gained from urban and agricultural water use efficiency, water reuse, and stormwater capture. The report, The Untapped Potential of California’s Water Supply, concludes that 10.8 to 13.7 million acre-feet of water per year could be provided though new supplies and demand reductions. At the August meeting of the California Water Commission, Dr. Peter Gleick from the Pacific Institute briefed the Commission on the results of the study.

Dr. Peter Gleick began by noting that the Pacific Institute has been working for the last 27 years on global water issues, climate change, and international conflicts as well as done extensive work on water in the western US and California. He said that during his talk today, he would discuss the report the Pacific Institute released about a month ago as well as discuss the idea of conservation and efficiency and some of the definitions and misconceptions and misunderstandings around that issue.

Dr. Peter Gleick began by noting that the Pacific Institute has been working for the last 27 years on global water issues, climate change, and international conflicts as well as done extensive work on water in the western US and California. He said that during his talk today, he would discuss the report the Pacific Institute released about a month ago as well as discuss the idea of conservation and efficiency and some of the definitions and misconceptions and misunderstandings around that issue.

The report, The Untapped Potential of California’s Water Supply, is a joint project with the University of California Santa Barbara, researchers at NRDC and at the Pacific Institute; the work was funded by the Pisces Foundation, the Hilton Foundation in LA, the California Water Foundation, and a variety of sources, he said.

The study looked at four pieces of the California water puzzle: Urban efficiency, agricultural efficiency, water reuse, and stormwater capture. “I’ll say right up front and we say explicitly in the report, California’s water problems and solutions are bigger than those four pieces of the puzzle,” he said. “We aren’t suggesting that those are the only four things we have to do, but we did an analysis of those four pieces of the puzzle to contribute to the conversation.”

The study looked at four pieces of the California water puzzle: Urban efficiency, agricultural efficiency, water reuse, and stormwater capture. “I’ll say right up front and we say explicitly in the report, California’s water problems and solutions are bigger than those four pieces of the puzzle,” he said. “We aren’t suggesting that those are the only four things we have to do, but we did an analysis of those four pieces of the puzzle to contribute to the conversation.”

“California’s water situation is complicated,” he said. “We use a lot of different types of water in a lot of different places for a lot of different purposes, for agriculture, for urban, urban use is split into residential, commercial and industrial. There’s a great diversity around the state in the way use water and in the demands and in the sources of supply.”

He then presented a graph depicting cumulative groundwater withdrawals from 1962 to present day. “We are extensively overdrafting groundwater,” he said. “Even in a good year, we’re overdrafting groundwater. During a drought, groundwater is the go-to source to replace missing surface water. We’re in a deep hole, and not only has California been incredibly dry the last three years, it’s been incredibly hot. This year is going to be a record high temperature year, hotter than it’s been in recorded 118-120 years, so it’s been hot and it’s been dry, and that’s part of the hole that we’re in.”

He then presented a graph depicting cumulative groundwater withdrawals from 1962 to present day. “We are extensively overdrafting groundwater,” he said. “Even in a good year, we’re overdrafting groundwater. During a drought, groundwater is the go-to source to replace missing surface water. We’re in a deep hole, and not only has California been incredibly dry the last three years, it’s been incredibly hot. This year is going to be a record high temperature year, hotter than it’s been in recorded 118-120 years, so it’s been hot and it’s been dry, and that’s part of the hole that we’re in.”

The study looked at urban efficiency, agricultural efficiency, water reuse, and stormwater capture, he said. He then presented a graph depicting the results for urban water use efficiency categorized by sector of water use: residential indoor water use, residential outdoor water use, commercial, institutional, and industrial, as well as conveyance system losses. He noted that red is existing water use. “The blue bars show our estimate of what efficient use would be if we were comprehensively using the technologies and practices we know work, that in fact we’ve been developing and applying in California for several decades, but not completely,” he said. “The green bar is the really optimistic, if we were really efficient, if we were maximizing technology and the policies and practices that we might do – Some of the things that Australia did after eight or nine years of drought when they were really up against the wall and they really had to push beyond the kinds of things that they had been doing day to day.”

The study looked at urban efficiency, agricultural efficiency, water reuse, and stormwater capture, he said. He then presented a graph depicting the results for urban water use efficiency categorized by sector of water use: residential indoor water use, residential outdoor water use, commercial, institutional, and industrial, as well as conveyance system losses. He noted that red is existing water use. “The blue bars show our estimate of what efficient use would be if we were comprehensively using the technologies and practices we know work, that in fact we’ve been developing and applying in California for several decades, but not completely,” he said. “The green bar is the really optimistic, if we were really efficient, if we were maximizing technology and the policies and practices that we might do – Some of the things that Australia did after eight or nine years of drought when they were really up against the wall and they really had to push beyond the kinds of things that they had been doing day to day.”

“This is total water use, applied water use, not consumptive,” Dr. Gleick said.

Dr. Gleick pointed out that the graph shoes that most urban water use is residential, which is about 50/50 between indoor and outdoor statewide, but varies depending on the region. “There’s much more outdoor water use in the Central Valley and the hotter areas, and there’s much more indoor in San Francisco where they don’t have much in the way of lawns.”

He then presented a slide depicting the residential per capita savings in gallons per day that is achievable by using more efficient dishwashers, faucets, showers, clothes washers, and toilets as well as leak repair. “The bars on the left show the potential savings in gallons per capita per day – the range in savings for applying indoor improvements and outdoor improvements, and it shows that there’s a lot of potential, especially on the outdoor side. We’ve done pretty well indoors, but outdoors, we could do a lot better which is why urban agencies now are beginning to focus on outdoor landscaping.”

He then presented a slide depicting the residential per capita savings in gallons per day that is achievable by using more efficient dishwashers, faucets, showers, clothes washers, and toilets as well as leak repair. “The bars on the left show the potential savings in gallons per capita per day – the range in savings for applying indoor improvements and outdoor improvements, and it shows that there’s a lot of potential, especially on the outdoor side. We’ve done pretty well indoors, but outdoors, we could do a lot better which is why urban agencies now are beginning to focus on outdoor landscaping.”

He noted that with really aggressive savings, we could cut residential water use substantially, as much as up to 50%. “We know that from experience in Australia that these are achievable; this is what really efficient residences could look like. There’s a conversation to be had here about what kind of gardens we want and what kind of lawns we want, if we want lawns and gardens. But these are achievable. Whether your savings occur inland or whether your savings occur at the coast make a difference as well.”

He then presented a slide depicting estimates of agricultural efficiency potential, noting that the first two bars are estimates of agricultural water savings from the CalFed studies in 2002 and 2006, and third are the estimated savings from Pacific Institute’s assessment that was done in 2009. “This graph actually does split out consumptive and non-consumptive savings,” he said. “The dark blue bars at the bottom are estimates of consumptive savings potential; the larger bar is overall non consumptive savings and the sum of the two is the estimate.” He noted that the numbers in the report reflect the 2009 Pacific Institute study, which showed a smaller potential than the CalFed estimates. “The agricultural sector has made enormous progress in recent years in improving efficiency, but there’s more that can be done.”

He then presented a slide depicting estimates of agricultural efficiency potential, noting that the first two bars are estimates of agricultural water savings from the CalFed studies in 2002 and 2006, and third are the estimated savings from Pacific Institute’s assessment that was done in 2009. “This graph actually does split out consumptive and non-consumptive savings,” he said. “The dark blue bars at the bottom are estimates of consumptive savings potential; the larger bar is overall non consumptive savings and the sum of the two is the estimate.” He noted that the numbers in the report reflect the 2009 Pacific Institute study, which showed a smaller potential than the CalFed estimates. “The agricultural sector has made enormous progress in recent years in improving efficiency, but there’s more that can be done.”

The other piece of the analysis looked at the potential for water reuse and stormwater capture. He presented a graph showing the trends for water recycling since 1970. “California has made some progress in improving recycled water production and use,” he said. “DWR estimates we’re using between 600,000 and 700,000 acre-feet of recycled water for a range of things. The pie chart looks at where that water is currently being applied. And some of it’s going to agricultural irrigation, urban landscaping and urban irrigation, groundwater recharge, recreational purposes, environment flows – reused water is used for all sorts of things.”

The other piece of the analysis looked at the potential for water reuse and stormwater capture. He presented a graph showing the trends for water recycling since 1970. “California has made some progress in improving recycled water production and use,” he said. “DWR estimates we’re using between 600,000 and 700,000 acre-feet of recycled water for a range of things. The pie chart looks at where that water is currently being applied. And some of it’s going to agricultural irrigation, urban landscaping and urban irrigation, groundwater recharge, recreational purposes, environment flows – reused water is used for all sorts of things.”

Dr. Gleick said the study looked at the potential to expand that, and he presented a chart of the results for water reuse potential. “We have a low estimate and a high estimate in our analysis,” he said. “The high estimate is if we do not do a lot more on urban water use efficiency, then a lot more water goes to our wastewater treatment plants, and so there’s much greater potential to them to take that water, treat it, and reuse it. If we’re really aggressive on urban efficiency, we cut flows to wastewater treatment plants, there’s less wastewater that can be reused, and that’s the low estimate.”

Dr. Gleick said the study looked at the potential to expand that, and he presented a chart of the results for water reuse potential. “We have a low estimate and a high estimate in our analysis,” he said. “The high estimate is if we do not do a lot more on urban water use efficiency, then a lot more water goes to our wastewater treatment plants, and so there’s much greater potential to them to take that water, treat it, and reuse it. If we’re really aggressive on urban efficiency, we cut flows to wastewater treatment plants, there’s less wastewater that can be reused, and that’s the low estimate.”

“Basically we’re saying we could double, potentially even triple the amount of water that could be reused from our urban systems,” he said. “A lot of this is already underway – a lot of the effort of the Governor’s budget and the bond is to expand funding for water reuse reflects that understanding of that potential.”

The other piece is stormwater capture and reuse. “This is an effort to expand our ability to capture stormwater that we currently divert and mostly throw away,” he said, presenting a slide depicting the stormwater capture potential in the various regions of the state. “There are a lot of efforts underway to try and figure out how to capture water either for immediate reuse and treatment or for groundwater recharge, and the estimate was about 400,000 or 500,000 or 600,000 of stormwater could potentially be capture above and beyond what’s now being captured, and instead of diverting it into our storm drains and into the ocean, it could be put to some sort of reuse.” He noted that a significant fraction of the potential is in Southern California, but coastal California in particular.

The other piece is stormwater capture and reuse. “This is an effort to expand our ability to capture stormwater that we currently divert and mostly throw away,” he said, presenting a slide depicting the stormwater capture potential in the various regions of the state. “There are a lot of efforts underway to try and figure out how to capture water either for immediate reuse and treatment or for groundwater recharge, and the estimate was about 400,000 or 500,000 or 600,000 of stormwater could potentially be capture above and beyond what’s now being captured, and instead of diverting it into our storm drains and into the ocean, it could be put to some sort of reuse.” He noted that a significant fraction of the potential is in Southern California, but coastal California in particular.

He then summarized the results. “The blue parts of the pie chart are reuse potential, the green is agricultural efficiency, the red is urban efficiency, the lighter blue is stormwater capture, and as you can see, different parts of the state have different potential,” he said. “Obviously there’s much more potential for agricultural efficiency improvements where agriculture has a big presence such as in the Central Valley, the Sacramento, San Joaquin, and Kern area, whereas urban efficiency potential improvements are greatest in our urban areas.”

He then summarized the results. “The blue parts of the pie chart are reuse potential, the green is agricultural efficiency, the red is urban efficiency, the lighter blue is stormwater capture, and as you can see, different parts of the state have different potential,” he said. “Obviously there’s much more potential for agricultural efficiency improvements where agriculture has a big presence such as in the Central Valley, the Sacramento, San Joaquin, and Kern area, whereas urban efficiency potential improvements are greatest in our urban areas.”

Dr. Gleick next addressed the idea of water use efficiency. “There’s a lot of misunderstanding about efficiency,” he said. “And there are different terms of art. Some people think conservation means letting your lawn go brown, taking a shorter shower – those things that save water. Those are things we do during droughts and the public’s pretty good about responding to voluntary requests to save water in an emergency.”

But efficiency’s a bit different. “Efficiency is the idea of doing what we want with less water,” he said. “You take a shower, but you do it with a efficient low flow shower head; it’s the same length of time for your shower, but you’re using less water. You flush your toilet with an efficient toilet, but you use less water than flushing it with an inefficient toilet. There’s a distinction between conservation and efficiency in our minds, and it’s an important one to keep in mind.”

There are a lot of different definitions of efficiency, and we’re not great at measuring how much we use beneficially versus non-beneficially and consumptively versus non-consumptively, he said. “Data is really an important part of this puzzle.”

The Pacific Institute has worked for a long time on the issue of conservation and efficiency, he said. “We think it’s a really important piece of the puzzle. We have never said it’s the only thing we have to do. Sometimes there are straw man arguments out there that say look, conservation and efficiency can’t solve all of our problems. I agree with that completely. Storage can’t solve all of our problems. Nothing is going to solve all of our problems because California water, as you know, is a complicated beast. But there are some misunderstandings about conservation and efficiency that I think are important to discuss and I want to present some of those.”

California has made remarkable progress on efficiency, he said. “Our total water use and our per capita water use have declined over the last 40 years, despite a growing population, despite a growing economy, in large part because of the efforts in the agricultural sector and the urban sector to do more with the water we already have. There are a lot of innovative people out there doing a lot of really innovative things.”

California has made remarkable progress on efficiency, he said. “Our total water use and our per capita water use have declined over the last 40 years, despite a growing population, despite a growing economy, in large part because of the efforts in the agricultural sector and the urban sector to do more with the water we already have. There are a lot of innovative people out there doing a lot of really innovative things.”

There is a new appreciation about the remaining potential and a growing understanding of the definitions and the complexities and that potential, as well as a growing effort to understand the barriers to implementation, he said. “Why is it difficult in some places and at some times to capture efficiency improvements? Is it economic, is it cultural, is it technological, is it measurement questions? There are a series of barriers to capturing efficiency improvements, and we’re trying to understand what those barriers are and overcome them.”

“But there are some serious misunderstandings and misrepresentations and constraints on implementation that we need to address,” he said, saying he would draw on five examples to describe the definitional questions and some of the misunderstandings:

Example #1. There is a city with one person living in it, who uses water to only grow a lawn, and he uses two units of water to do so. No water goes downstream. “If that person uses one unit on their lawn and the other unit actually waters the sidewalk, the one unit on the lawn is beneficial use and it’s consumptive; it goes to the atmosphere, nobody else can use it. The one unit on the sidewalk is non-beneficial and it’s consumptive. What’s the fix? One fix is to fix the sprinkler system so it’s only watering the lawn. And you save a consumptive unit that can go downstream. That’s new water.”

Example #2. Same city, one person living there using two units, all of it beneficially on a lawn; now waste, no downstream flow. “One of the options in the conservation efficiency discussion is replace your lawn with a nice drought resistant garden that may only use one unit. So now it’s using one unit; that one unit that’s being used is still consumptive, it goes to the atmosphere because it’s evapotranspired away like any crop, and it’s beneficial because it’s being used productively, and the other unit becomes available to go downstream. It’s new water. That is a xeriscaping type of response.”

Example #3. Same city, one person living there, only using water in the toilet. “The water is used beneficially, but it’s not consumptive because it’s captured, it goes to a wastewater treatment plant, it’s treated, and it goes downstream to the next user. It is a beneficial use but not consumptive. You could replace your toilet with a toilet that only uses one unit, but people say to me, why bother, you have two units going downstream anyway. It’s not producing new water. It has to be new water, sometimes people claim.”

But here’s the issue, he said. “By only using one unit instead of two, you don’t have to treat two units of wastewater; you treat one. There’s a savings there. Even if you’re not producing new water, that’s a savings. It’s what we call co-benefits. You’re not taking two units out of the stream; you’re leaving one instream; maybe there’s an ecosystem benefit. That’s a co-benefit. There are energy savings for not pumping that water out and pumping it to the treatment plant; there are energy savings. So sometimes conservation and efficiency produce the savings that are not new water, but are still worthwhile doing.”

“This is an important point,” said Dr. Gleick. “The argument that conservation of efficiency has to produce new water is wrong. Sometimes, it produces new water but not always. As the ag picture showed that even if it’s not new water, it can often produce energy savings, ecosystem savings, water quality savings, and so on.”

Example #4. Same city, one person, two units of water used for a toilet and there’s a drought. Only one unit of water is available. “If they are using a high efficiency toilet that only uses one unit, they are more drought proof so it provides drought savings as well. Now you may no longer have that extra unit going down the stream because of the drought, but conservation and efficiency provides drought benefits as well. If you’ve been using one unit instead of two for many years, there’s more water stored in your reservoir upstream, you’re taking less water out of groundwater, and over time, these savings can accumulate over multiple years.”

Example #5. Same city, one person living there using two units of water, and now another person wants to move in. There are only two units available and this person is using it on a high flow toilet. “A new person moves to Sacramento and there’s no water for that person, but if that person is using a high efficiency toilet uses one unit, and the new person moves to the city and only also only uses one unit, you can have a growing population or a growing economy without new supply – without having to boost that two units to three units by building storage upstream or by finding something else.”

“Some people believe that the water use efficiency potential is small, and if that’s true, then our only options are find new supply, fallow land in the ag sector, or limit population growth in our urban areas, things that are really difficult for us to discuss as a policy in California,” said Dr. Gleick. “There are things we don’t want to do. We don’t want to fallow land and we don’t want to talk about limiting population. We do talk about new supply and I think the conversation about developing new supply is a perfectly legitimate one. The question should be yield. That’s what this beneficial-non-beneficial, consumptive-non consumptive issue is.”

The good news is that the assumption that the water efficiency potential is small is wrong. “There’s plenty of potential still, and despite the efforts that have already been made, a lot more could be done to capture inefficient uses around the state, and that’s going to allow us to maintain our agricultural sector and our urban sectors in a much stronger position than otherwise,” he said.

After the report was released, an op-ed in the Bee said there couldn’t possibly be 10 to 14 MAF of new water, said Dr. Gleick. “We never said that 14 MAF was new water, we were very explicit that some of it was new water and some of it was non-consumptive use that had other benefits. Some of this is new water in the agricultural sector; some of it’s not. In the urban sector, some of it is new water that can be reallocated, and some of it isn’t.”

Co-benefits are often ignored in the conversation about efficiency, but they are important. “Co-benefits being the reduced wastewater treatment costs, the reduced energy costs, and the ecosystem instream flow benefits of conservation and efficiency,” he said. “Saving a gallon of water in LA with a low-flow toilet is a better thing to do than saving a gallon of water in San Francisco with a low-flow toilet as it takes a lot more energy to pump that water to Los Angeles and the energy savings has to be considered.”

Co-benefits are often ignored in the conversation about efficiency, but they are important. “Co-benefits being the reduced wastewater treatment costs, the reduced energy costs, and the ecosystem instream flow benefits of conservation and efficiency,” he said. “Saving a gallon of water in LA with a low-flow toilet is a better thing to do than saving a gallon of water in San Francisco with a low-flow toilet as it takes a lot more energy to pump that water to Los Angeles and the energy savings has to be considered.”

It’s not just efficiency of water; it’s productivity of water use, Dr. Gleick said. “The point is we don’t want to use water; we want to do things. We want to grow food and fiber. We want to make semiconductors. We want industry and agriculture. So what is really important is what we get out of the water we use – yield per unit of water. Farmers understand this. Or dollars per unit of water, or employment per unit of water, or other measures; there are other ways of measuring water use productivity then just how much water is being used.”

Another co-benefit is the ability to delay or eliminate spending on new infrastructure, he said. “We may have to build new surface storage; we certainly need groundwater storage. But if our ability to use water more efficiently delays expenditures in a cost –effective way on that new infrastructure, that’s an economic benefit. It depends on whether expenditures on efficiency are more effective than expenditures on storage or wastewater treatment or stormwater capture; that’s an economic balance question. But I would argue that we can delay or eliminate enormous infrastructure cost with lower cost expenditures on efficiency and conservation.”

Dr. Gleick acknowledged that there are many examples in the agricultural sector of moving to drip irrigation without a change in the total amount of water used. “People say, drip irrigation doesn’t save any water. Or sometimes doesn’t save any water. We know it does, sometimes,” he said. “But the other part of that discussion is that sometimes it leads to an enormous improvement in yield. You’re using the same amount of water but you’re growing more food with the same amount of water. There is the yield per unit of water, reduced disease outbreaks, improved crop quality, and reduced energy use. The agricultural sector has been really good about describing all these co-benefits associated with these kinds of improvements.”

He then presented a slide showing the economic productivity per acre-foot, noting that the state has been improving the dollars per acre-foot for decades. “We get more dollars in the ag sector out of every acre-foot of water that we use now, and this is corrected for inflation. This is another measure of efficiency and productivity. “

He then presented a slide showing the economic productivity per acre-foot, noting that the state has been improving the dollars per acre-foot for decades. “We get more dollars in the ag sector out of every acre-foot of water that we use now, and this is corrected for inflation. This is another measure of efficiency and productivity. “

He presented another slide showing crop productivity per acre-foot of water. “We’ve also been improving yields. This is tons of field and seed crops per acre-foot of water applied, and it shows an improvement in yield.”

He presented another slide showing crop productivity per acre-foot of water. “We’ve also been improving yields. This is tons of field and seed crops per acre-foot of water applied, and it shows an improvement in yield.”

So even if the total amount of water stays the same, income can go up and productivity can go up; these are benefits of some of these efforts to improve efficiency,” he said. “The purpose of improving efficiency is not just to free up new water for reallocation. Efficiency improvements can lead to productivity, quality, financial improvements, and these are real benefits.”

What happens with the saved water is another really important point, Dr. Gleick said. “I’ve often heard that we save water through efficiency improvements, but it just gets reused so there are no real savings. That’s a policy question. What we do with saved water is a policy question. If a farmer improves water use efficiency on farm, and doesn’t return that water to instream flows, that’s a policy question. If that farmer then uses that water for expanded production, again, there may be no decrease in water use, but there may be an increase in crop productivity and income. Those are policy questions.”

“If we save water and don’t return it to instream flows, there are no instream flow benefits, but that’s a policy question,” he continued. “If we save water by low flow toilets and efficient washing machines, and the population grows and we just give that water to a bigger population, again, no water may be saved but we’re serving more people, and those are benefits to the state, and we see this in the exponential growth of our economy and the exponential growth of our population, and the fact that total water use hasn’t gone up, but the policy question about what we do with saved water is a tough one. I don’t have an answer for you about that.”

“There should be some new discussion on a policy level about to capture and monetize or allocate these co-benefits,” he said. “Often the benefits don’t accrue to the person who is saving the water and so there’s no real incentive to save water. They might accrue to somebody else, and that’s a policy question as well.”

“So I’m going to stop there … “

Discussion highlights

Commissioner Saracino said that he was concerned that the numbers in the report might do a disservice to policy discussions on the implication that there’s all this new water to be gained, especially from agricultural water use efficiency. “I think that doesn’t allow us to get into the real policy discussion that you mentioned, the fact that we may need to fallow land or find ways to control consumptive use of water … it seems like the new water estimates are grossly exaggerated, and again that concerns me because of the implications on the real policy discussions that we need to have … “

“On the issue of new water, we never said the numbers in our report were all new water,” he said. “That was a misrepresentation of our report, and our report’s pretty clear about that. … I think there’s still a substantial amount of consumptive use that can be saved that would be new water. Outdoor landscape in the residential urban sector is enormous, frankly, and the biggest part of our urban savings is landscape savings, and that’s a consumptive use. In the agricultural sector, our estimates of new water are pretty much in line with the CalFed estimates and DWR estimates. I think there’s lots of discussion that could be had on really how much there is and how do you capture it, but it’s a little difficult to respond to misrepresentations of the report versus what the reality is.”

Commissioner Del Bosque asks Dr. Gleick to expand on what he meant about evaporative losses.

“This is an important part of the beneficial non-beneficial, consumptive non-consumptive discussion,” he said. “There are evapotranspiration losses from agriculture; that’s what agriculture is about. You’re growing things; plants use water, and they evapotranspire that water. That’s a productive beneficial use of water. You can’t grow crops without it. What I’m interested in is unproductive evaporative losses, and unproductive evaporative losses are losses from watering the sidewalk. so it evaporates into the air and doesn’t produce a benefit, or unproductive losses from sprinkler systems that are evaporating into the air and not benefitting the crop and there are plenty of those … So there are productive and unproductive evaporative losses. We don’t very accurately measure unproductive evaporative losses, and yet we know that they exist. It’s not 0, it’s something, and if we can figure out how to capture unproductive evaporative losses, that’s new water. That’s, at the moment, a non beneficial consumptive use of water. So that’s the distinction.”

“I have to agree with Commissioner Saracino that I think the numbers are grossly overstated here,” said Commissioner Orth. “Coming from the Tulare Lake Basin, I have a hard time getting my arms around the concept of 2.5 MAF down there being available for management in a different way, or as potential new water supply. The California Irrigation Institute a few years ago did an analysis that came up with a significantly less number of savings potential or new water potential in the Tulare Lake hydrologic region, which I think substantiates the point that we need to have more discussion and dialog about this … “

“I did read the report,” said Commissioner Delfino. “It was very informational and helpful. And putting aside the issue of water savings and what does that actually mean, I appreciate the fact that the report came out at a time that rebalanced the conversation in what we should be doing to address the drought, and to focus it on the multitude of actions that we need to take in addition to infrastructure, but also efficiency, conservation, and so I appreciate that … “

“There are barriers to anything we do in California,” said Dr. Gleick. “There are a lot of tools for capturing conservation and efficiency, and we’ve written about this at the Institute pretty extensively. We don’t have a preferred tool. There are regulatory requirements that we have to do; appliance standards in California drove the national standards on water efficiency and have been incredibly important; that’s a regulatory tool. There are financial tools – the pricing of water and the development of water markets that permit saved water to be transferred, or for somebody to benefit economically from conservation and efficiency or water pricing structures at utilities, or meters, or education – all of those things are important … “

For more information …

- Click here for the webcast of the August meeting of the California Water Commission. This is agenda item 9.

- Click here for the agenda and meeting materials.

- Click here for the issue brief on the report, The Untapped Potential of California’s Water Supply.

- Click here for the Water Efficiency Infographic.

- Click here for Peter Gleick’s Power Point Presentation.

Get the Notebook blog by email and never miss a post!

Get the Notebook blog by email and never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!