With much of the state’s water supply originating in the mountains as precipitation on the forested landscape, the health and management of the upper watersheds are critically important to California’s water quality and water supply. At the August meeting of the California Water Commission, George Gentry with the California Board of Forestry and Fire Protection, and Dr. Martha Conklin and Dr. Roger Bales from UC Merced discussed the relationships between forests and water.

George Gentry, Executive Officer of the California Board of Forestry and Fire Protection

“Water has been a dominant issue in front of the Board of Forestry and Fire Protection for well over 30 years for various reasons,” began George Gentry. “I don’t envy the task that this Commission has because if there’s a more controversial issue than water, I couldn’t imagine what it is. It really dominates our discussions because depending on what statistic you look at, 80 to 85% of the water of the state of California originates of the forested landscape.”

Through the Fire and Resources Assessment Program (FRAP), the Board does a statewide assessment that considers how forest management and fire management ties into various issues. The most recent FRAP was completed in 2010. “It’s very similar to the approach in the California Water Plan; in fact, the FRAP people worked very closely with the folks on the California Water Plan,” said Mr. Gentry.

Through the Fire and Resources Assessment Program (FRAP), the Board does a statewide assessment that considers how forest management and fire management ties into various issues. The most recent FRAP was completed in 2010. “It’s very similar to the approach in the California Water Plan; in fact, the FRAP people worked very closely with the folks on the California Water Plan,” said Mr. Gentry.

This assessment informs us as to what we’re going to do with our strategies such s the annual report and the Strategic Fire Plan, said Mr. Gentry. “Every so often, we do a strategic fire plan,” he said. “The new strategic fire plan is very forward looking. It’s been very effective for us and it’s helped us with establishing relationships with various other groups. All these things have their basic strategy formulated by what we find out in the FRAP assessment.”

The 2010 FRAP assessments identified priority landscapes, such as water supply and water quality. “What we did was we looked at assets and threats and identified priority landscapes,” he said, presenting a slide of a map of priority landscapes for water supply in California. “The assets are surface water runoff, surface water storage, and forest meadows, and the threats are impervious surfaces, climate change, localize development threat, and water demand, and what you get is a map that looks like this,” he said, noting that the high priority landscapes are designated in red. “The Sierra Nevada and the Cascades dominate the high priority landscapes, and that makes sense because a good portion of the water comes from those particular areas and feeds into the Sacramento.”

The 2010 FRAP assessments identified priority landscapes, such as water supply and water quality. “What we did was we looked at assets and threats and identified priority landscapes,” he said, presenting a slide of a map of priority landscapes for water supply in California. “The assets are surface water runoff, surface water storage, and forest meadows, and the threats are impervious surfaces, climate change, localize development threat, and water demand, and what you get is a map that looks like this,” he said, noting that the high priority landscapes are designated in red. “The Sierra Nevada and the Cascades dominate the high priority landscapes, and that makes sense because a good portion of the water comes from those particular areas and feeds into the Sacramento.”

Water quality assets are fish, wild and scenic rivers, riparian vegetation, and forest meadows; the threats are impaired water bodies, post fire erosion, and impervious surfaces, he said, presenting a map showing the high priority landscapes. “This map varies a little differently from the previous one in that the high priority landscapes shift a little more towards the coast,” he said. “That’s mainly a function of the geology; there is more clay and more suspended sediment in those particular soils.”

Water quality assets are fish, wild and scenic rivers, riparian vegetation, and forest meadows; the threats are impaired water bodies, post fire erosion, and impervious surfaces, he said, presenting a map showing the high priority landscapes. “This map varies a little differently from the previous one in that the high priority landscapes shift a little more towards the coast,” he said. “That’s mainly a function of the geology; there is more clay and more suspended sediment in those particular soils.”

High intensity, large scale fires are the most dramatic thing that happens to water quality in the forestry world, he said, drawing on the Bagley Fire that occurred two years ago as example. The Bagley fire was a 46,000 acre fire that started in the Pitt River; after a few days, the wind shifted and the fire went into the Mc Cloud. “It was a very high intensity fire which was very difficult to control and very difficult to contain, and both these arms feed into Shasta.”

High intensity, large scale fires are the most dramatic thing that happens to water quality in the forestry world, he said, drawing on the Bagley Fire that occurred two years ago as example. The Bagley fire was a 46,000 acre fire that started in the Pitt River; after a few days, the wind shifted and the fire went into the Mc Cloud. “It was a very high intensity fire which was very difficult to control and very difficult to contain, and both these arms feed into Shasta.”

He then presented some slides showing the aftermath. “We had storms that winter, and there was sheet erosion off this road,” he said. “There was gullying and almost a flash flood scenario. With the net result being downstream deposition. This impacts you because water storage is reduced by all this sediment coming down,” he said.

(Trouble viewing the gallery? Click here for a pdf version.)

One thing we do for issues like this is meadow restoration, Mr. Gentry said. “The Board initiated regulations several years ago to help with Aspen meadow restoration which is important for groundwater preservation,” he said. “What we did is we looked at regulations that would make it easier for landowners to remove conifers and bring these meadows back.”

One thing we do for issues like this is meadow restoration, Mr. Gentry said. “The Board initiated regulations several years ago to help with Aspen meadow restoration which is important for groundwater preservation,” he said. “What we did is we looked at regulations that would make it easier for landowners to remove conifers and bring these meadows back.”

Mr. Gentry said that California has the most comprehensive riparian management regulations in the United States and the world for forest management. “We went through a three-year process to review and revise our regulations,” he said. “They are very technical; they are very complex, but they are very protective of riparian management. Most all the studies I have seen show that landowners do a fantastic job in restoring and maintaining their riparian vegetation.”

Mr. Gentry said that California has the most comprehensive riparian management regulations in the United States and the world for forest management. “We went through a three-year process to review and revise our regulations,” he said. “They are very technical; they are very complex, but they are very protective of riparian management. Most all the studies I have seen show that landowners do a fantastic job in restoring and maintaining their riparian vegetation.”

Another issue is large wood placement. “Sometimes science tells you one thing and it turns out to be wrong,” he said. “In the 50s and 60s we all believed that removing large woody debris from the watershed was the best possible thing for fish, so we did, and we stripped it clean. Bad move. So now we’re busy, putting it all back in. Part of the deal with our riparian management rules is to retain trees that will provide this, but we’re actually providing reviews for how we can put this in. This is important, not only for fish habitat in making pools, but helping to meter the sediment downstream as it helps retain the sediment.”

Another issue is large wood placement. “Sometimes science tells you one thing and it turns out to be wrong,” he said. “In the 50s and 60s we all believed that removing large woody debris from the watershed was the best possible thing for fish, so we did, and we stripped it clean. Bad move. So now we’re busy, putting it all back in. Part of the deal with our riparian management rules is to retain trees that will provide this, but we’re actually providing reviews for how we can put this in. This is important, not only for fish habitat in making pools, but helping to meter the sediment downstream as it helps retain the sediment.”

Defensible space is another issue. “Now defensible space may or may not have a direct impact on water quality or water supply, but what it does for us in terms of the fire management regime is that it makes it so we can utilize our resources better for fighting fires as we don’t have to allocate quite as much to defending structures.”

Fuel breaks are used to help control the spread of large-scale fires. He presented a slide of a fuel break. “This one is in the Oakland Hills, and as you can see in the background, you have eucalyptus, invasive pine, and various things. This is an area that in 1989 suffered a catastrophic fire, and this is the kind of management that happens around some of these communities that can impact water supplies.”

Fuel breaks are used to help control the spread of large-scale fires. He presented a slide of a fuel break. “This one is in the Oakland Hills, and as you can see in the background, you have eucalyptus, invasive pine, and various things. This is an area that in 1989 suffered a catastrophic fire, and this is the kind of management that happens around some of these communities that can impact water supplies.”

“The Board is currently in the process of reviewing its vegetation treatment program through a programmatic environmental impact review,” he said. “One of the things we can do is try to lower the fire intensity by doing controlled burns. This is a very tricky thing to do, though, and to do it well. It keeps fuels down, it keeps fire intensity lower, and it keeps the fire down on the ground, rather than crowning out. But you also come up against the air quality regulations and burn days are not plentiful, so you have to take your opportunities when you can get them. Right now in the drought season,it is very difficult to find optimum conditions.”

Thinning to reduce stand density is another action the Board has been working on, he said. “We have these stands that are far denser than what existed prior to settlement in California, so we’ve made a series of regulations that facilitate thinning in these stands, and I want to show you the reason why,” he said, presenting a slide with four pictures on it. “This is the same picture through several iterations: 1909, 1938, 1958, and finally 1979. This is what fire suppression does. It allows for the encroachment and growing of additional trees and increases the density. The picture in 1909 shows an area that if a fire started, it would probably creep along the ground and go below all these trees and not do anything more than a very low intensity burn. The picture in 1979 is a disaster waiting to happen.”

Thinning to reduce stand density is another action the Board has been working on, he said. “We have these stands that are far denser than what existed prior to settlement in California, so we’ve made a series of regulations that facilitate thinning in these stands, and I want to show you the reason why,” he said, presenting a slide with four pictures on it. “This is the same picture through several iterations: 1909, 1938, 1958, and finally 1979. This is what fire suppression does. It allows for the encroachment and growing of additional trees and increases the density. The picture in 1909 shows an area that if a fire started, it would probably creep along the ground and go below all these trees and not do anything more than a very low intensity burn. The picture in 1979 is a disaster waiting to happen.”

The Board has worked very hard the last two years at revising and revamping the road rules, Mr. Gentry said. “The handbook for forest ranch and rural roads was just completely revamped,” he said. “It’s now a very good, state of the art document on road construction, and it just became available. And the other is the Board of Forestry Technical Rule Addendum that we just released which focuses on hydrologic disconnection, road drainage, minimization of the diversion potential and high rise crossings.”

“What we found in our monitoring is that if there’s going to be a problem with our roads, it’s most likely going to occur at road crossings, and that’s where the tricky part comes in so we worked very hard on updating that,” he said,noting that the new practices include making sure culverts are on grade, not plugged, and are sized for 100-year intervals.

“What we found in our monitoring is that if there’s going to be a problem with our roads, it’s most likely going to occur at road crossings, and that’s where the tricky part comes in so we worked very hard on updating that,” he said,noting that the new practices include making sure culverts are on grade, not plugged, and are sized for 100-year intervals.

The Forest Practice Rules Implementation and Effectiveness Monitoring program (FORPRIEM) has determined that where the rules are implemented and done correctly, they are effective, but where there’s a departure from that practice, there can be failures, said Mr. Gentry. The Board is now looking at increasing education and training for all operators and foresters. The Board recently formed an Effectiveness and Monitoring Committee as part of their adaptive management program to monitor the effectiveness of the rules and adjust them, if necessary, to be more effective.

Rules and regulations recently adopted by the Board include emergency notice for fuel hazard reduction, anadromous salmonid protection rules, operations on saturated soils, aspen and meadow restoration, modified THP for fuel hazard reduction, road rules, defensible space regulations, emergency regulations for water drafting, and forest fire prevention exemption. The Board recently adopted emergency regulations for water drafting in light of the drought. During operations, roads are watered to keep the dust down. “In this era of drought, that’s a big concern, so we have new rules in place to further evaluate whether or not that’s the appropriate practice,” he said.

Mr. Gentry then turned to the impacts of illegal marijuana grows. “This problem has really exploded over the last few years,” he said. “I’ve spent most of my life in Humboldt County so I’m very familiar with the problem, but this is way beyond anything I’ve ever seen in my life. … I’m just going to say it plain right now. These are carpetbaggers. These are people coming from God knows where, but they are not from around there … They think it’s the Wild West, so they come out there and they basically grab land wherever they can get it. They are not purchasing this land; they are going out on public land, national forest land, and timber company land.”

Mr. Gentry then turned to the impacts of illegal marijuana grows. “This problem has really exploded over the last few years,” he said. “I’ve spent most of my life in Humboldt County so I’m very familiar with the problem, but this is way beyond anything I’ve ever seen in my life. … I’m just going to say it plain right now. These are carpetbaggers. These are people coming from God knows where, but they are not from around there … They think it’s the Wild West, so they come out there and they basically grab land wherever they can get it. They are not purchasing this land; they are going out on public land, national forest land, and timber company land.”

Typically, they dig a pit and line it; they fill it with water diverted from the creek, they add fertilizer, then they put it on drip irrigation, he explained. “That fertilizer causes an algal bloom; they divert it from a headwater creek which in turn destroys the habitat downstream. They also leave the trash there.” They are using toxic chemicals such as rodenticides and carbofuoron, which impact wildlife and endanger people who encounter these grow sites, he said.

“These kind of things have a very high impact, especially in Humboldt County,” said Mr. Gentry. “In a drought year, when you’re dewatering all the headwater streams, habitat suffers.”

“So with that, thank you very much … “

Dr. Martha Conklin, Director of Natural Reserves, UC Merced

Dr. Martha Conklin from UC Merced then discussed water in the Sierra Nevada forest and montane water balances. Sixty percent of the state’s consumable water comes off of the Sierra Nevada, so it’s very important for our water supply, she said.

She began by presenting a slide depicting a montane water balance. “Most of the snow that becomes runoff comes about 9000 feet, which is much below where we do a lot of our monitoring, so we have this vision that we should scatter measurements throughout the landscape,” she said. “Here’s a landscape where we are using satellite measurements or LIDAR and snow depth sensors, trying to pick a mixture between spatial and point measurements. You measure your headwater streams so you know how much water is coming off of them. You measure the water depth because there is quite a bit of storage in that subsurface in these forested catchments, as well as looking at soil moisture. And the obscure looking flux tower that measures the respiration of the forest, because tied very much in that water balance is how much water the trees use, especially now that we have these very dense forests.”

She began by presenting a slide depicting a montane water balance. “Most of the snow that becomes runoff comes about 9000 feet, which is much below where we do a lot of our monitoring, so we have this vision that we should scatter measurements throughout the landscape,” she said. “Here’s a landscape where we are using satellite measurements or LIDAR and snow depth sensors, trying to pick a mixture between spatial and point measurements. You measure your headwater streams so you know how much water is coming off of them. You measure the water depth because there is quite a bit of storage in that subsurface in these forested catchments, as well as looking at soil moisture. And the obscure looking flux tower that measures the respiration of the forest, because tied very much in that water balance is how much water the trees use, especially now that we have these very dense forests.”

She next presented a slide with a very simple water balance. Precipitation, which is mostly snow, equals the amount of water lost to evapotranspiration and transpiration by the trees, and runoff, she said, noting that the trees use a lot, probably even most of the water.

She next presented a slide with a very simple water balance. Precipitation, which is mostly snow, equals the amount of water lost to evapotranspiration and transpiration by the trees, and runoff, she said, noting that the trees use a lot, probably even most of the water.

Most of the snow falls above 9000 feet, she said, presenting a graph of the Merced River basin, noting that the x axis is elevation and the y axis is the fraction of snowmelt coming out. “About 30% of the snowmelt comes out between 9000 and 10,000 feet,” she said. “That’s also where we have the least amount of land, because the mountains are steep. It is also where we have our forests. So one of the issues facing forest management is understanding the effect of forest management on water over the whole wide range of physiographic conditions in California, with the Sierra Nevada being the most important one as well as understanding how much evapotranspiration occurs across vegetation types.”

Most of the snow falls above 9000 feet, she said, presenting a graph of the Merced River basin, noting that the x axis is elevation and the y axis is the fraction of snowmelt coming out. “About 30% of the snowmelt comes out between 9000 and 10,000 feet,” she said. “That’s also where we have the least amount of land, because the mountains are steep. It is also where we have our forests. So one of the issues facing forest management is understanding the effect of forest management on water over the whole wide range of physiographic conditions in California, with the Sierra Nevada being the most important one as well as understanding how much evapotranspiration occurs across vegetation types.”

Dr. Conklin next presented a slide comparing a picture of the Feather River watershed from 1890 and 1993, noting that while it is an individual shot, keep in mind that the increased density is happening all over the landscape. “A survey that was done in the Sierra National Forest showed that we have about four times as many stems on the land then we did a hundred years ago, but we only have twice as much biomass, so a lot of these stems are small trees, and they are the ones that really add to the fire danger because they are the ladder fuels that bring those flames right up to the top.”

Dr. Conklin next presented a slide comparing a picture of the Feather River watershed from 1890 and 1993, noting that while it is an individual shot, keep in mind that the increased density is happening all over the landscape. “A survey that was done in the Sierra National Forest showed that we have about four times as many stems on the land then we did a hundred years ago, but we only have twice as much biomass, so a lot of these stems are small trees, and they are the ones that really add to the fire danger because they are the ladder fuels that bring those flames right up to the top.”

Something to think about is how different the forest are now compared to pre-fire suppression, and can they be returned to those conditions, she said, noting that it involves a lot of questions because there are many people living now in forests and the urban-wild interface. “But if we were able to do that, at least on selected parts of the landscape, what would that have the effect on these restored forests on water yield?” she said. “We basically think it should increase it, but let’s go back and look at how trees and snow work together.”

Trees have been around for millions of years, and they are optimized for water gathering, she said. Their branches come down in “v”s and they have a dark trunk and a dark body so they absorb heat, she explained. “They block the low angle sunlight coming and they shade the snow so it stays on the ground, and because we depend on the snow providing water storage for about six months of the year, so they are important, so we can’t get rid of them. In fact, we don’t’ want catastrophic fires from that viewpoint.”

Trees have been around for millions of years, and they are optimized for water gathering, she said. Their branches come down in “v”s and they have a dark trunk and a dark body so they absorb heat, she explained. “They block the low angle sunlight coming and they shade the snow so it stays on the ground, and because we depend on the snow providing water storage for about six months of the year, so they are important, so we can’t get rid of them. In fact, we don’t’ want catastrophic fires from that viewpoint.”

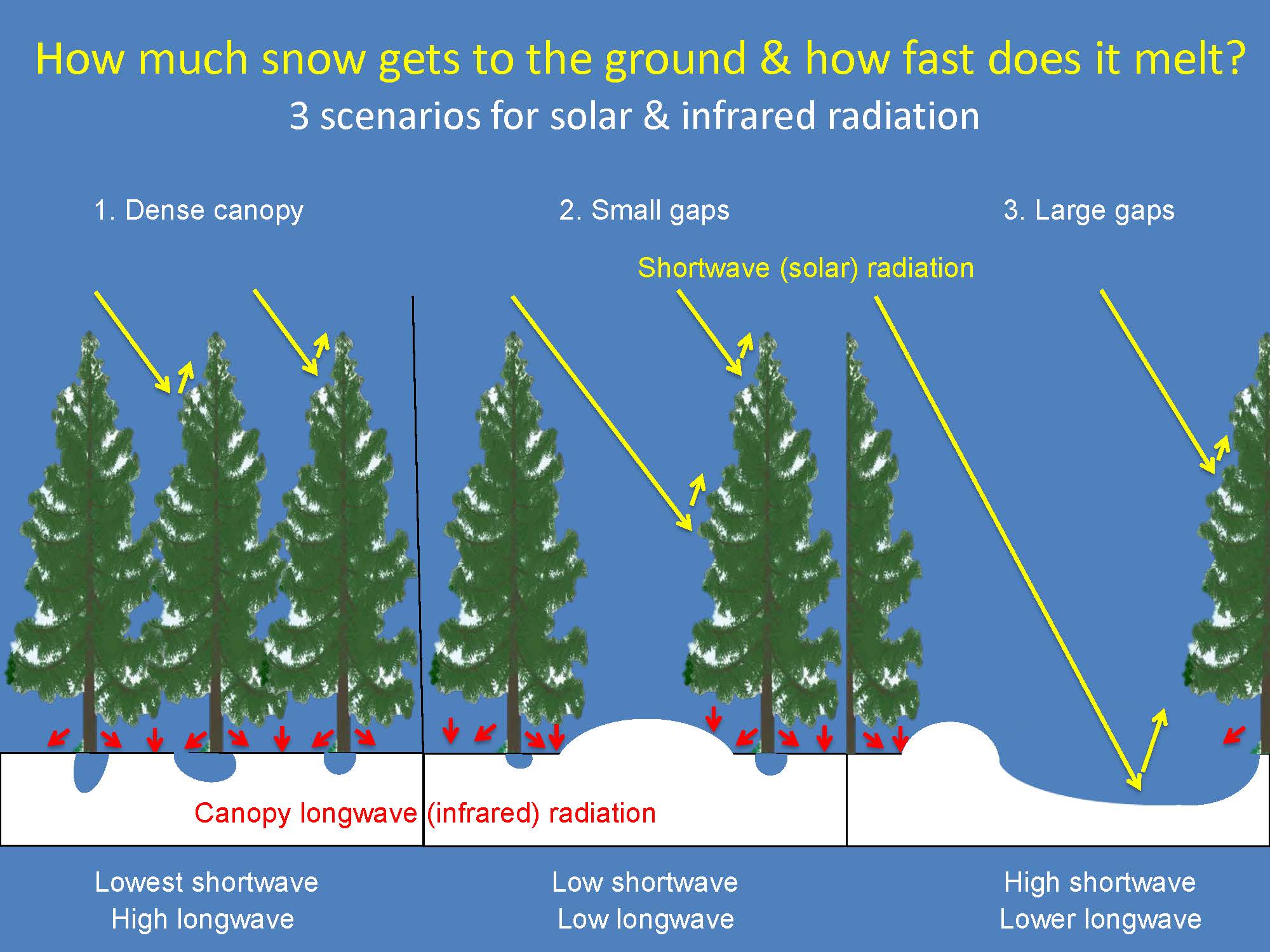

The trees intercept snowfall, so of the snow that falls on the tree, about 20% goes back into the air; it sublimes, she said. “The rest of it melts and kind of falls down the tree trunk and probably infiltrates into the ground, and that provides ready water for winter respiration. They also emit long-wave radiation that melts the snow, which creates tree wells. That’s because the trees get warm and they melt the snow.”

Dr. Conklin said that the effect of the dense canopy is that it stops the snow from getting to the ground. “If we go back to pre-fire suppression when there were bigger gaps between the trees, there will be more snow on the ground,” she said. “If the gaps are the right size, they will continue to shade that snowpack so we’ll have it around for the six months that we want. If you make the gaps too large like you might see after a big fire, the sun’s going to hit it, and it’s going to sublime. The snow’s going to warm up and go up in the atmosphere or melt.”

Dr. Conklin said that the effect of the dense canopy is that it stops the snow from getting to the ground. “If we go back to pre-fire suppression when there were bigger gaps between the trees, there will be more snow on the ground,” she said. “If the gaps are the right size, they will continue to shade that snowpack so we’ll have it around for the six months that we want. If you make the gaps too large like you might see after a big fire, the sun’s going to hit it, and it’s going to sublime. The snow’s going to warm up and go up in the atmosphere or melt.”

A study is being done in the Stanislaus-Tuolumne experimental forest where they did various types of treatments, such as different variable thinning or even spaced thinning. “Unfortunately, the study started in 2012, so we didn’t get a lot of snow for the years we wanted to look at it, but it did give some telling results.”

A study is being done in the Stanislaus-Tuolumne experimental forest where they did various types of treatments, such as different variable thinning or even spaced thinning. “Unfortunately, the study started in 2012, so we didn’t get a lot of snow for the years we wanted to look at it, but it did give some telling results.”

Dr. Conklin noted that in the slide, the forest was thinned back to pre-fire suppression levels. “With current regulations you can’t thin to this level. This was a scientific experiment so we were allowed to thin to this. This is about 50% of tree mass removal.”

Dr. Conklin noted that in the slide, the forest was thinned back to pre-fire suppression levels. “With current regulations you can’t thin to this level. This was a scientific experiment so we were allowed to thin to this. This is about 50% of tree mass removal.”

She then presented a slide with a graph plotting evapotranspiration against precipitation. “This is the snow depth, looking at the unthinned one, versus the even and variable thinned ones, and while there’s a large spread in the measurements, you can see that there’s more snow that’s gathered when you have those spacings. We would hope that this would give a higher water yield.”

She then presented a slide with a graph plotting evapotranspiration against precipitation. “This is the snow depth, looking at the unthinned one, versus the even and variable thinned ones, and while there’s a large spread in the measurements, you can see that there’s more snow that’s gathered when you have those spacings. We would hope that this would give a higher water yield.”

An Australian hydrologist did a study looking globally at watersheds where tree density was reduced, looking at the response for increasing water yield. “It’s pretty drastic, reduce canopy cover about 40%, you can increase water yields by about 9%, based on this. With this type of indication, we think you can increase water yields if we do reduce the forest cover, but we do need studies to determine the appropriate level of the treatments.”

Dr. Conklin then discussed the Southern Sierra Critical Zone Observatory. UC Merced received a grant from NSF, so with that funding, they’ve located flux towers and instruments up the side of the mountain to capture data from the different vegetation zones, such as measuring what the trees are doing or look at soil moisture, she said. The data they are collected is uploaded to CDEC so it’s publicly accessible, she added.

Dr. Conklin then discussed the Southern Sierra Critical Zone Observatory. UC Merced received a grant from NSF, so with that funding, they’ve located flux towers and instruments up the side of the mountain to capture data from the different vegetation zones, such as measuring what the trees are doing or look at soil moisture, she said. The data they are collected is uploaded to CDEC so it’s publicly accessible, she added.

Dr. Conklin said they have been studying two watersheds, one in the American River and one in the Sierra National Forest, for seven years as part of the Sierra Nevada Adaptive Management Project, and the results are consistent between these two studies.

Not only are we interested in the forests, we’re very interested in the resiliency of the landscape and how much water is captured in groundwater, she said. “Forests have a lot to do with how much soil is located at the different elevations,” she said. “There are deeper soils and eroded bedrock in these 6000 foot watersheds and these 4000 foot watersheds, but up at 9000 feet, you don’t have a lot of the soil, so maybe more of the water runs off. We have put out a number of instruments … we have three instrumented catchments plus a larger catchment surrounding them in a variety of different measurements, and we think this is really important because if you’re going to understand what goes in the forest, snow isn’t a nice uniform layer, so a point measurement doesn’t help. You need to have it scattered throughout the watershed.”

Not only are we interested in the forests, we’re very interested in the resiliency of the landscape and how much water is captured in groundwater, she said. “Forests have a lot to do with how much soil is located at the different elevations,” she said. “There are deeper soils and eroded bedrock in these 6000 foot watersheds and these 4000 foot watersheds, but up at 9000 feet, you don’t have a lot of the soil, so maybe more of the water runs off. We have put out a number of instruments … we have three instrumented catchments plus a larger catchment surrounding them in a variety of different measurements, and we think this is really important because if you’re going to understand what goes in the forest, snow isn’t a nice uniform layer, so a point measurement doesn’t help. You need to have it scattered throughout the watershed.”

One of the first things they focused on was how much water ends up going underground. “Our preliminary estimates that about an equal amount of snow sits above the ground as water that goes that beneath it in these elevations,” she said. “So when we talk about these landscapes, you can’t just look at what’s sitting up there; you have to look at what’s underneath that, and that becomes really important. If you think about our forest resilience, because that’s why some of our forests are not dead now after a third year of drought is that they have a lot of water they have access to. And that’s also why we have some headwater streams that are still running, even though we’ve had very little snow.”

We wanted to study how this affected the way ways trees breathe and how much water they use, so we put flux towers up the side of the mountain, Dr. Conklin said. “A flux tower is a tower that has to be above the top of the tree canopy. It measures the carbon dioxide that comes out of the trees so we know how much they are respiring, and we measure water vapor so we know how much they are transpiring. How much of that water they are bringing up and releasing up into the atmosphere. We can also measure evaporation in terms of that.”

We wanted to study how this affected the way ways trees breathe and how much water they use, so we put flux towers up the side of the mountain, Dr. Conklin said. “A flux tower is a tower that has to be above the top of the tree canopy. It measures the carbon dioxide that comes out of the trees so we know how much they are respiring, and we measure water vapor so we know how much they are transpiring. How much of that water they are bringing up and releasing up into the atmosphere. We can also measure evaporation in terms of that.”

There’s a lot of variety as the elevation rises, from the oak savannah at about 2000 feet, the pine-oak forest at 4000 feet, the mixed conifer at about 7000 feet, to the sub-alpine at 9000 feet, she said. She noted that the precipitation and the amount the trees are using are noted on the slide. “We get the highest precipitation in the subalpine forest that’s above 9000 feet – about 33” there. Some of the trees at the lower elevations are using more than they are getting, so they are using some of the runoff from the higher elevations. In the pine-oak forest, the precipitation is lower than what the trees are using. The mixed conifers are the places where the trees are beginning to use less water than what’s coming in precipitation. This is why we think managing the forest would help water yield because we have this dense forest and it’s using that water.”

There’s a lot of variety as the elevation rises, from the oak savannah at about 2000 feet, the pine-oak forest at 4000 feet, the mixed conifer at about 7000 feet, to the sub-alpine at 9000 feet, she said. She noted that the precipitation and the amount the trees are using are noted on the slide. “We get the highest precipitation in the subalpine forest that’s above 9000 feet – about 33” there. Some of the trees at the lower elevations are using more than they are getting, so they are using some of the runoff from the higher elevations. In the pine-oak forest, the precipitation is lower than what the trees are using. The mixed conifers are the places where the trees are beginning to use less water than what’s coming in precipitation. This is why we think managing the forest would help water yield because we have this dense forest and it’s using that water.”

She then presented another graph depicting water use in feet per year at the various elevations, broken into three zones. “The reason that the trees the lower elevation don’t use more water is the summers are so dry and so hot, they shut off in the summer time. We call the zone between 3000 and 7000 feet the sweet spot or the happy zone for trees, because those trees go all winter long; they melt that water as it comes in and they keep transpiring . You can see that they have some of the highest evapotranspiration. When you get up to the zone where the snow accumulates, that’s where the trees shut down in the winter time because it’s too cold, so they use less water.”

She then presented another graph depicting water use in feet per year at the various elevations, broken into three zones. “The reason that the trees the lower elevation don’t use more water is the summers are so dry and so hot, they shut off in the summer time. We call the zone between 3000 and 7000 feet the sweet spot or the happy zone for trees, because those trees go all winter long; they melt that water as it comes in and they keep transpiring . You can see that they have some of the highest evapotranspiration. When you get up to the zone where the snow accumulates, that’s where the trees shut down in the winter time because it’s too cold, so they use less water.”

Dr. Conklin noted that the data presented here is before the drought, but one of the things that is most interesting is that the trees at this zone are not reducing transpiration due to the drought. “This really tells you how much storage is in the ground; they are tapping that extra water, so they have some resiliency.” She noted this was last year’s data; they don’t have this year’s data yet.

They recently did a timber harvest in the CZO that was uneven aged thinning and very low level, only about 15 to 20% of the biomass. “We were hoping to see some water yield but we saw nothing,” she said. “It was too low a level to see any difference, and the drought totally obscured anything we would have seen from this.”

They recently did a timber harvest in the CZO that was uneven aged thinning and very low level, only about 15 to 20% of the biomass. “We were hoping to see some water yield but we saw nothing,” she said. “It was too low a level to see any difference, and the drought totally obscured anything we would have seen from this.”

“At the 6000-7000 feet area, we have measured that they are resilient to drought,” said Dr. Conklin. “With the thick soil layer and the eroded bedrock layer that they have, there’s enough water stored there, and that’s also probably why some of the headwater streams are still going. At the lower elevation, about 4000 feet, those trees immediately felt water stress with the drought; they don’t have that resilience. And even lower, same thing – nothing there. So it’s really that high elevation zone, that overgrown zone that really is important one in terms of looking at forest management.”

“We think vegetation removal can result in more runoff, but it has to be done scientifically,” said Dr. Conklin. “We don’t know that optimum level yet. … We did a 15 to 20% removal and we didn’t see an effect with the drought at all … We’re talking about getting back to pre-fire suppression levels and that’s something that we don’t’ have regulations set up to do that very well over the landscape.”

Dr. Conklin said that research out of Berkeley has shown that if the vegetation is cleared out due to fire or removal, it will revegetate in about 30 years. “These trees are not going to just not populate the landscape, especially if there’s water available,” she said. “So in terms of thinking about this as a management problem, it’s one that’s going to be reoccurring. It’s not something you can just do one time. This is something that has to be built into budgets.”

Dr. Conklin said that research out of Berkeley has shown that if the vegetation is cleared out due to fire or removal, it will revegetate in about 30 years. “These trees are not going to just not populate the landscape, especially if there’s water available,” she said. “So in terms of thinking about this as a management problem, it’s one that’s going to be reoccurring. It’s not something you can just do one time. This is something that has to be built into budgets.”

The benefit is if we do them right, they’ll shade that snowpack, and with climate change, they increase the elevation,” she said. “Spring is coming earlier so we do want to keep that solid precipitation as long as possible. Our whole water system is set up with it storing up there and then coming down at the right time of the year.”

“There are still a lot of unknowns, but we’re certainly gaining insight,” she said. “We still are working on how much water is used by vegetation, we really want to understand that deep subsurface layer and really how it plays in terms of water storage and drainage out; we really want to understand these interceptions, sublimation and evaporative losses; and we need to do some experiments looking at what are the vegetation and thinning effects on the timing of snowmelt and runoff because I don’t think we should do large areas until we have some well constrained studies.”

“And with that … “

Dr. Roger Bales, Director of the Sierra Nevada Research Institute, UC Merced

“I’m going to put this in a water resources context and talk about some of the things I think we can do to take advantage of the science for better water,” began Dr. Bales.

“When I think of water security, I like to talk about the three “I”s: Infrastructure, institutions, and information,” he said. “We need infrastructure, particularly storage, because storage across the world is highly correlated with water security. We need stronger institutions and California is working on through Integrated Regional Water Management to strengthen our institutional capability to manage water. But to me, the foundation of this is better and more accessible information.”

“When I think of water security, I like to talk about the three “I”s: Infrastructure, institutions, and information,” he said. “We need infrastructure, particularly storage, because storage across the world is highly correlated with water security. We need stronger institutions and California is working on through Integrated Regional Water Management to strengthen our institutional capability to manage water. But to me, the foundation of this is better and more accessible information.”

“We’ve been operating a lot of our water systems by the seat of our pants with limited information,” he said. “We’re doing a good job but the physical climate and the institutional climate is changing, and there’s a need for better water information.”

Dr. Bales said the he defines water security to include both quantity and quality of water, flood control and so forth, as well as water supply, but that he is going to focus mainly on water supply today. “I’ll say that water security lies at the heart of adapting to climate change. We’ve got to adapt our water.”

The California Water Action Plan does mention the critical need to expand storage capacity, but Dr. Bales thinks of storage in a much broader context than just dams. “The Sierra Nevada snowpack in an average year, has storage equal to about half of the capacity behind the rim dams in the Sierra Nevada, so the snowpack and the soil water together are about equal to the rim dams.”

He then presented a slide from the California Roundtable Report in 2012. “In making a water secure California, I want to bring in the idea of ecosystem services or managing forests, as water supply management translates into ecosystem services, be it wetlands or forests.”

He then presented a slide from the California Roundtable Report in 2012. “In making a water secure California, I want to bring in the idea of ecosystem services or managing forests, as water supply management translates into ecosystem services, be it wetlands or forests.”

Dr. Bales said he liked the ACWA policy principles on improved management of California’s headwaters. “I think the water industry is well aware qualitatively of the water implications of forests and headwater management, and as they say in this policy principle, California can no longer afford to relegate management of its headwaters to the margin. We need to pay some attention to them. As everybody knows, water doesn’t bubble up in the Delta, it comes from the Sierra Nevada.”

So why do we need a new water information system? “I contend that an accurate transparent and timely water accounting can transform operation of our infrastructure and the institutional response to change,” he said. “That is, if we’re making good forecasts around water, then we can do better, we can stretch our water supply to better meet the needs of the state, so we need credible, legitimate, salient information at the proper spatial scale. Fortunately, the technology has advanced tremendously in the last few years and we can now do that at an affordable level.”

So why do we need a new water information system? “I contend that an accurate transparent and timely water accounting can transform operation of our infrastructure and the institutional response to change,” he said. “That is, if we’re making good forecasts around water, then we can do better, we can stretch our water supply to better meet the needs of the state, so we need credible, legitimate, salient information at the proper spatial scale. Fortunately, the technology has advanced tremendously in the last few years and we can now do that at an affordable level.”

“We need to understand how water flows through the system at a more disaggregated level and not just the general broad scale,” he said. “And we need to give water management institutions the data and information so they can evolve decision making. I think we’ve seen through history how better data and better measurements can drive innovation. It certainly drove water quality regulations since the 1970s and it can drive water quantity innovations, too.”

He then gave an example. The seasonal forecasts from the Sierra Nevada are based on manual monthly measurements which started in 1904. “We’re still using the same technology today,” he said, noting that some automated sensors were put in during the 1970s. “They are pretty good if they are near the average snow accumulation. We can predict the runoff reasonably well. You get to a wet year or a dry year, you have a lot of error in that, so on a year-to-year basis, we need to be able to adapt better technology and we can. The technology is available to improve these forecasts and many other types of forecasts or outlooks.”

He then gave an example. The seasonal forecasts from the Sierra Nevada are based on manual monthly measurements which started in 1904. “We’re still using the same technology today,” he said, noting that some automated sensors were put in during the 1970s. “They are pretty good if they are near the average snow accumulation. We can predict the runoff reasonably well. You get to a wet year or a dry year, you have a lot of error in that, so on a year-to-year basis, we need to be able to adapt better technology and we can. The technology is available to improve these forecasts and many other types of forecasts or outlooks.”

New measurement technologies include blending satellite data with wireless sensor networks, which rely on low-cost sensors spread across the landscape, and using aircraft laser imaging, or LIDAR. “It’s only been within the last five or ten years that this knowledge has come along to the point where we can use it operationally in remote areas like the Sierra Nevada or groundwater areas,“ he said.

New measurement technologies include blending satellite data with wireless sensor networks, which rely on low-cost sensors spread across the landscape, and using aircraft laser imaging, or LIDAR. “It’s only been within the last five or ten years that this knowledge has come along to the point where we can use it operationally in remote areas like the Sierra Nevada or groundwater areas,“ he said.

He then presented slides showing the different sensors that they have installed at the critical zone observatory. He explained that to get the signals through the forest, they hop the signal from sensor to sensor through radios and then up to a satellite or cell phone to transmit the data quickly. “This system has been in place for about six years,” said Dr. Bales. “We’ve been put in several hundred soil moisture sensors and several dozen snow sensors in the Sierra Nevada.”

He then presented slides showing the different sensors that they have installed at the critical zone observatory. He explained that to get the signals through the forest, they hop the signal from sensor to sensor through radios and then up to a satellite or cell phone to transmit the data quickly. “This system has been in place for about six years,” said Dr. Bales. “We’ve been put in several hundred soil moisture sensors and several dozen snow sensors in the Sierra Nevada.”

UC Merced has received a $2 million grant from the National Science Foundation to build a larger scale research observatory in the American River Basin. “We’re working with the operational agencies to try and make this a core element for what could be part of a water information system for California, answering questions like how much snow is out there,” he said. “We can answer how much snow is at a certain meadow at a certain snow pillow, but that doesn’t tell us how much is across the landscape. We can use a small number of spatially distributed sensors to answer questions like how much snow is out there, how much soil moisture is out there, and what are the characteristics of the water balance across the landscape.”

UC Merced has received a $2 million grant from the National Science Foundation to build a larger scale research observatory in the American River Basin. “We’re working with the operational agencies to try and make this a core element for what could be part of a water information system for California, answering questions like how much snow is out there,” he said. “We can answer how much snow is at a certain meadow at a certain snow pillow, but that doesn’t tell us how much is across the landscape. We can use a small number of spatially distributed sensors to answer questions like how much snow is out there, how much soil moisture is out there, and what are the characteristics of the water balance across the landscape.”

The goals of this basin-scale observatory are to demonstrate real time intelligent water information and work with operational agencies to use these data to reduce uncertainty in forecasts, he said. “Those forecasts then can potentially feed into operations. Can you imagine operating Folsom Dam based on forecasts instead of just rule curves? Or enhance hydropower operations because that’s where the real money is. If you can keep your water level a little bit higher and optimize when you ‘re releasing water based on knowing how much is coming in, that’s real money for the water agency or utility.”

The goals of this basin-scale observatory are to demonstrate real time intelligent water information and work with operational agencies to use these data to reduce uncertainty in forecasts, he said. “Those forecasts then can potentially feed into operations. Can you imagine operating Folsom Dam based on forecasts instead of just rule curves? Or enhance hydropower operations because that’s where the real money is. If you can keep your water level a little bit higher and optimize when you ‘re releasing water based on knowing how much is coming in, that’s real money for the water agency or utility.”

“We need spatially distributed information if we’re going to document the impacts of forest management,” he said. “To do sustained forest management is going to cost more than the landowners and land managers have available currently to do that. If you’re going to ask for additional costs, I really think you need to verify the impacts of that and we can’t do that with just a model. I can change a parameter in a model and show you that you get more runoff, but there’s no verification unless you have the measurements out there and this same system provides that verification.”

“These measurements provide unprecedented accuracy and really provide what I feel California is due for and that’s an upgraded water information system,” said Dr. Bales.

“These measurements provide unprecedented accuracy and really provide what I feel California is due for and that’s an upgraded water information system,” said Dr. Bales.

“Sustained forest management that provides measurable benefits is going to require investments, not only in research but in verification and maintenance,” he said, noting that the next step is a scalable demonstration project.

Better information is a critical foundation for water security, especially in a warming and more-variable climate, and the American River basin is both research platform and a core element of new water-information system, he said.

“I’ll leave you with these final thoughts,” said Dr. Bales. “With better informed management, California’s water supply can go much further. I’ve focused on forests, but I think the same need for better information applies to groundwater, ag water use, urban water use, because if you’re talking about water conservation, you need verification as well as technology development.”

“I’ll stop there … “

Discussion highlights

Commissioner Curtin asks Dr. Bales about the costs of the monitoring system he presented.

“To build out the American River Basin, to provide the accurate distributed information that could feed into the next generation of forecast models or decision tools, we’re talking somewhere between $2 and $4 million, probably,” responded Dr. Bales. “These may be high from an operational standpoint, but we need the research verification to go along with it, so that includes some of the research verification. An annual O&M cost would be much lower … “

Commissioner Del Bosque refers to the pictures of the forests pre-fire suppression and now. He asks how did the forests maintain that lower density then and how are we going to achieve that now?

“The lower densities are basically a function of a couple of things,” said Mr. Gentry. “One, Native Americans were very keen on burning off lands because the grass output next year is much improved and it keeps the area open and allows for wildlife to move freely through and that’s what they wanted to achieve. And two, even when there are lightning strikes, in the absence of suppression in an ecosystem like that, they’ll burn at a low intensity and they’ll keep the stocking levels down.”

Mr. Gentry said that the Board of Forestry needs to look at is what kind of stocking levels should be required post harvest and what things should we be seeing on the ground. “A key issue to me is allowing for reintroduction of low intensity fire to help control things,” he said.

Commissioner Delfino asks about meadows.

Dr. Conklin replied that they are monitoring some meadows as part of their project. “When you look at a catchment, meadows are incredibly important, they are really important for biodiversity, but if you look at the area of the catchment, and the area of the meadow, and if you start thinking about that water storage, there’s a lot more water in the whole catchment than there is in the meadow. The reason meadows exist is that they are groundwater discharge points, often starting at the beginning of a stream running through them, but that’s where the groundwater comes out due to bedrock controls, so what we’re trying to do is put those meadows in terms of the whole catchment process. They are incredibly important for the biodiversity of the whole system; they are low-sloped so they capture a lot of sediments and are really important for the water quality, but I don’t think you can understand the groundwater flow in the system unless you think about the whole catchment.”