At the July 22 meeting of Metropolitan Water District’s Special Committee on the Bay-Delta, David Fullerton, Principal Resource Manager, discussed the cooperative studies that are underway with the Department of Fish and Wildlife and UC Davis to develop more understanding of some basic questions about the longfin smelt.

The longfin smelt in the Bay-Delta are one of at least 20 populations of longfin smelt that are found in estuaries, rivers, and lakes from Alaska to California. The Bay-Delta population of longfin smelt has been listed as a threatened species under state endangered species regulations, and has been found to be a species warranting protection under federal regulations, although the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service hasn’t listed it at this time due to the need to address other high priority actions. The longfin smelt is of particular importance to the Bay Delta Conservation Plan, as it is not only one of the Plan’s eleven covered fish species, but also a determining factor in the decision tree’s outcome for the spring outflow criteria.

David Fullerton began by saying his presentation today would focus on the longfin smelt, one of three key species in the Bay-Delta system: the Delta smelt, longfin smelt, and salmon.

“It’s a very important species,” he said. “It’s pretty small, just a few inches long. It actually lives all the way from San Francisco Bay up to Alaska. … There really isn’t a lot of sampling going on outside of the Bay.” He noted that part of smelt’s lifecycle is spent in the Pacific Ocean with the San Francisco Bay being the southernmost edge of its range.

He then presented a slide with a graph showing longfin abundance. “First of all, let me say, this is on a log scale, which is a very important thing to notice,” he said. “This represents the Fall Midwater Trawl Index, which is an index of fish in Suisun Bay and in the Delta. This is considered by many – although not necessarily by me – a representation of relative abundance from year to year of longfin smelt.”

He then presented a slide with a graph showing longfin abundance. “First of all, let me say, this is on a log scale, which is a very important thing to notice,” he said. “This represents the Fall Midwater Trawl Index, which is an index of fish in Suisun Bay and in the Delta. This is considered by many – although not necessarily by me – a representation of relative abundance from year to year of longfin smelt.”

He pointed out that longfin population drops during the dry years, recovers somewhat during the wet years, but since the 1960s, the general trend has been downward. “So from a value of something like 100,000 in 1967, we see a value as low as 10 in about 2007 or 2008, and this is really a huge drop,” he said. “If this weren’t on log scale, basically, it would look like a flat line after the year 2002 or 2003, so this is an index that’s dropped dramatically. When regulators look at this, they are very concerned about the species. Even though this is only part of the longfin range, it still looks like they are becoming extirpated in this southern part of the range.”

This has repercussions for the State Water Board standards for the Bay Delta system, he said. “The longfin smelt is effectively the backbone of our X2 regulations in the spring, for example – this is the key species upon which winter-spring outflow standards are based. It’s also listed under the California Endangered Species Act, and under the federal act, Fish & Wildlife Service has said that it deserves to be listed, but they don’t have the staff time to actually do it yet, so it’s definitely a species that’s linked to operations, so we need to try to understand what’s going on with this fish and keep it healthy.”

He then presented a slide titled, Abundance-Flow Relationship. “This is another way of presenting some of the data I just showed you,” Mr. Fullerton said. “This is one of the key graphs that you will see that has driven the discussion over longfin.” He explained that the X axis is Delta outflow during the winter and spring on a log scale which starts at 2000 cfs, which would be very low, all the way up to 200,000 cfs which would be extraordinarily high average outflow; and the Y axis is the same Fall Midwater Trawl index that he showed on the last graph.

He then presented a slide titled, Abundance-Flow Relationship. “This is another way of presenting some of the data I just showed you,” Mr. Fullerton said. “This is one of the key graphs that you will see that has driven the discussion over longfin.” He explained that the X axis is Delta outflow during the winter and spring on a log scale which starts at 2000 cfs, which would be very low, all the way up to 200,000 cfs which would be extraordinarily high average outflow; and the Y axis is the same Fall Midwater Trawl index that he showed on the last graph.

There are a couple of things to notice here, he said. “One is that this is a really good correlation for biology,” he said. “I’m the physics major, and this would be terrible in physics, but this is really good for biology. It’s a very consistent trend; more water means more fish.” He pointed out that in the early years, more water used to mean a lot of fish, and that over the years, the line is dropped from the purple to the red to the green. “You can see that it appears that if you add water you get more fish, but you’re getting fewer and fewer fish for the same number of acre-feet of water over time.”

“This justifies this idea that they are heading toward extinction due to food supply limitations or to bad habitat – people aren’t sure what’s going on, but flow still looks like it’s a good tool for protecting this fish, so there’s still a very strong impetus for increasing Delta outflow,” Mr. Fullerton said. “And in fact, as the numbers get lower, the impetus for increasing flows gets even higher because people are thinking it’s getting closer and closer to extinction so we have to do everything we can.”

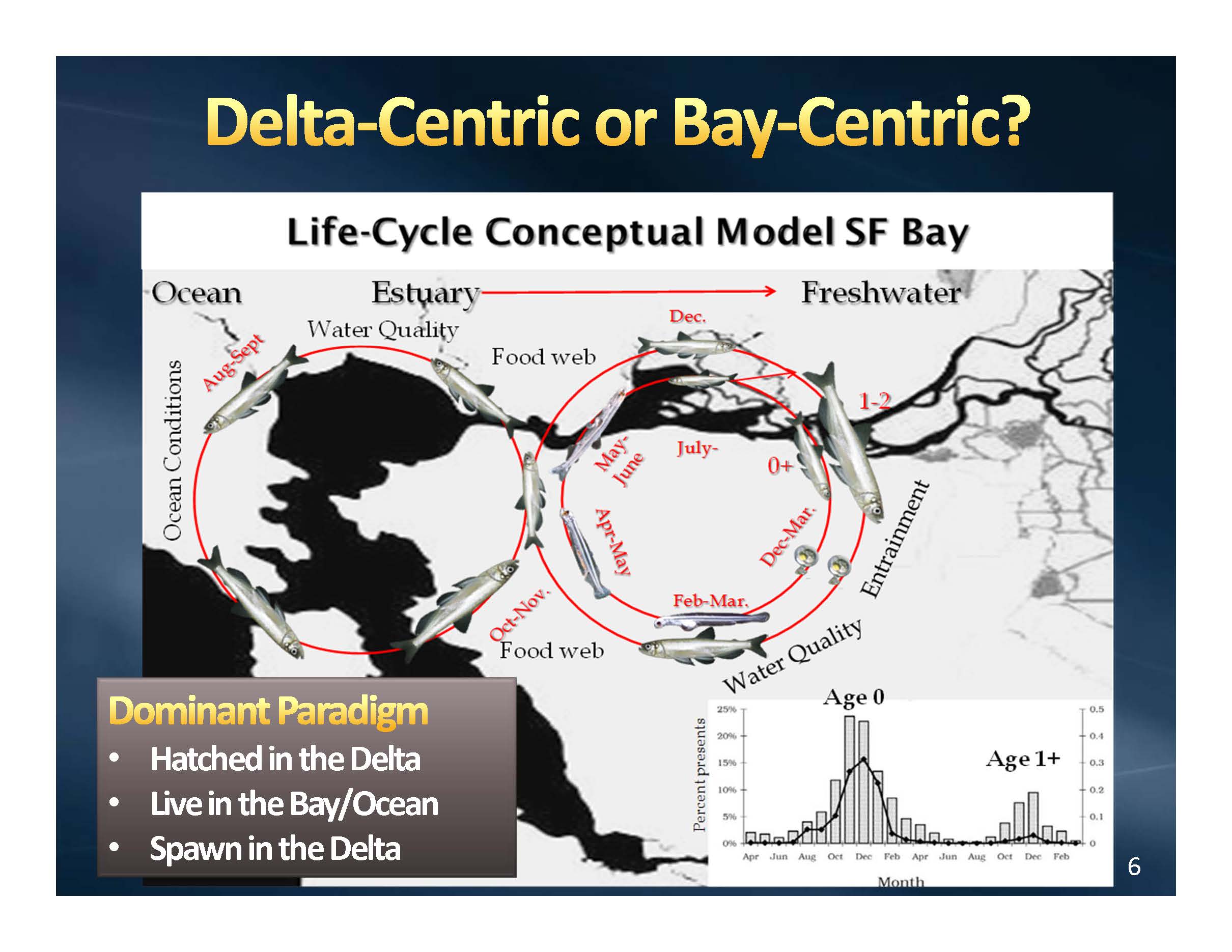

This graph is the centerpiece of a paradigm of the longfin life cycle that is heavily intertwined with project operations, he said. “The idea is that outflow really matters. Even though this is a fish that goes all the way up to Alaska, basically there’s a sub-population in this paradigm that lives in the Bay that goes up into the Delta to spawn after its about 2 years old. Somehow those outflows improve the success of its spawning and of the new hatch each year, and so more water somehow generates more fish up in the Delta, and then the Delta swim back down into the Bay and even into the Pacific Ocean, returning two years later, a little bit like salmon.”

This graph is the centerpiece of a paradigm of the longfin life cycle that is heavily intertwined with project operations, he said. “The idea is that outflow really matters. Even though this is a fish that goes all the way up to Alaska, basically there’s a sub-population in this paradigm that lives in the Bay that goes up into the Delta to spawn after its about 2 years old. Somehow those outflows improve the success of its spawning and of the new hatch each year, and so more water somehow generates more fish up in the Delta, and then the Delta swim back down into the Bay and even into the Pacific Ocean, returning two years later, a little bit like salmon.”

“That’s the standard paradigm,” he said. “It’s one where you would emphasize Delta outflow to protect the fish and it’s one in which you would think that the fish were highly vulnerable to entrainment at the export facilities because they are all up in the Delta for a couple of months, either the adults that are laying eggs or the larvae right after they’ve been hatched, so there are tremendous linkages to project operations.”

With the longfin smelt, as well as a lot of other fish, there are a number of ways of looking at the same data, he said. “At Metropolitan and among various water contractors, we’re looking at alternative concepts for what may actually be happening with this fish,” he said. “Longfin and Delta smelt aren’t like buffalo or other animals that you can watch what they are doing all the time. You can’t put GPS recorders on them. … You simply have to infer a lot about what’s going on with these fish. You put out a net, you catch a couple, you put out a net a year later, you catch a different number and you’re trying to infer what all that means.”

Mr. Fullerton said it was much like having only 100 pieces of a 1000-piece jigsaw puzzle. “You’re trying to figure out what the picture is but you’ve only got a few pieces, and so there are a lot of different ways you could rearrange those pieces to get something that looks like a coherent picture,” he said.

There are alternate ways of looking at the data which are equally valid, given what we know about the longfin smelt, he said. “An alternative theory is that no, they don’t’ go up into the Delta; these aren’t salmon,” he said. “The Bay is essentially a convoluted piece of shoreline, as far as they are concerned, and they are going to the nearest bit of freshwater they can find to spawn, whether it’s in San Jose or Palo Alto or Napa River or Petaluma, or the Delta. They are looking for a place to spawn. They are not particularly close to the projects. And if that’s the case, our hypothesis is that the abundance, the apparent linkage between abundance and flow isn’t caused by Delta outflow; it’s caused by the fact that all flows are high in a wet year. Delta outflow is high, and every other stream that rings that Bay Area is also high during a wet year.”

“There’s another index of abundance which shows almost no decline over the last 30 years,” he said. “And so we’re wondering what’s going on, we have one index that shows them apparently going extinct, and we have another one that shows that their population has been remarkably stable, so what gives? Which one is it? Let’s look at the data.”

He then presented a distribution map of longfin smelt of spawning age from the Bay study. “This is the time when they are supposed to be laying their eggs,” he said. “You don’t particularly see any tendency for them to be in the Delta. This is an average distribution for longfin smelt. They are all over the place, the edge of their distribution is in the Delta, the upper edge, but they go all the way down to San Jose into the South Bay. Under the existing theory, that the idea is that when it’s time, this little two inch fish goes up into the Delta 70 miles, but you don’t see any evidence of that in the distribution. So this to me supports the idea that they are hanging out until its time and then they are going to the shore and looking for a place to lay their eggs.”

He then presented a distribution map of longfin smelt of spawning age from the Bay study. “This is the time when they are supposed to be laying their eggs,” he said. “You don’t particularly see any tendency for them to be in the Delta. This is an average distribution for longfin smelt. They are all over the place, the edge of their distribution is in the Delta, the upper edge, but they go all the way down to San Jose into the South Bay. Under the existing theory, that the idea is that when it’s time, this little two inch fish goes up into the Delta 70 miles, but you don’t see any evidence of that in the distribution. So this to me supports the idea that they are hanging out until its time and then they are going to the shore and looking for a place to lay their eggs.”

He then presented a slide depicting the comparison of Delta outflow patterns to Bay tributary patterns. “This is an average of all the different tributaries I could find data for from the USGS,” he said. “There’s dozens of streams that flow into the Bay, and you can see that starting from 1962 all the way through 2010, the flow patterns are indistinguishable. Statistically you can’t tell the difference, so if you’re getting an abundance boost in wet years, you don’t really know if its Delta outflow, which would then be linked to increased outflow from the projects, or whether it’s just runoff coming into the Bay. You can’t tell the difference.”

He then presented a slide depicting the comparison of Delta outflow patterns to Bay tributary patterns. “This is an average of all the different tributaries I could find data for from the USGS,” he said. “There’s dozens of streams that flow into the Bay, and you can see that starting from 1962 all the way through 2010, the flow patterns are indistinguishable. Statistically you can’t tell the difference, so if you’re getting an abundance boost in wet years, you don’t really know if its Delta outflow, which would then be linked to increased outflow from the projects, or whether it’s just runoff coming into the Bay. You can’t tell the difference.”

“Finally, here’s the tale of two different indexes,” he said, presenting a slide comparing the Fall Midwater Trawl index against the Bay Study’s Otter Trawl. “This is starting in 1980, so it’s starting later than the one I showed you before, but you can see that in 1980, we’re looking at something close to 10,000, and now we’re down to something like 100, so that’s a two order of magnitude drop in apparent abundance in the Fall Midwater Trawl.”

“Finally, here’s the tale of two different indexes,” he said, presenting a slide comparing the Fall Midwater Trawl index against the Bay Study’s Otter Trawl. “This is starting in 1980, so it’s starting later than the one I showed you before, but you can see that in 1980, we’re looking at something close to 10,000, and now we’re down to something like 100, so that’s a two order of magnitude drop in apparent abundance in the Fall Midwater Trawl.”

“But look at the blue line,” he pointed out. “This is a different trawl; this is a different net, it’s a net that basically scrapes the bottom, it’s designed to catch things that live on the bottom. It has weights on it so it’s running right on the bottom, and then it has some floats on it so it’s about 1 foot high, and it’s just a lift that captures stuff on the bottom. And they catch a lot of longfin smelt in this net, and you can see that there’s been essentially no decline in that catch of longfin smelt at all in the last 30 years. “These can’t both be right, so this really motivates us to try to figure out which one is right, or perhaps, why they’re both wrong. The truth may be in the middle somewhere, we don’t really know.”

He said there are different signals and different data out there that potentially could support different hypotheses, which would lead to dramatically different management interventions. “If you think of a Delta centric strategy, outflow matters because that’s where longfin are spawning because they are upstream. Entrainment matters because they are so close to the pumps, especially in dry years, and they’ve been crashing. That’s the paradigm we’ve been living under for a long time.”

“The alternative paradigm we want to study is basically that Delta outflow isn’t all that important because that’s just one more tributary and it’s dozens of tributaries around the Bay that are actually driving the big wet year increases in abundance,” he said. “Entrainment doesn’t matter because only a few longfin are that high up in the system, and that we haven’t seen a big drop in abundance in longfin.”

“The alternative paradigm we want to study is basically that Delta outflow isn’t all that important because that’s just one more tributary and it’s dozens of tributaries around the Bay that are actually driving the big wet year increases in abundance,” he said. “Entrainment doesn’t matter because only a few longfin are that high up in the system, and that we haven’t seen a big drop in abundance in longfin.”

“These are starkly different views of the fish, and I’m not saying that I can prove that the Bay centric is correct, but what we want to do is study it and try to figure out which one of these is right, or whether it’s something in the middle,” he said.

“The State Water Contractors had sued over their listing of longfin, and we’d sued them over their take limits and their restrictions on Old and Middle River flows, and as a settlement of that lawsuit, we agreed to a cooperative study of longfin which is what we’re doing now,” he said.

He then discussed the elements of the study.

“The first is just the question, if under my hypothesis, longfin smelt are spawning all around the Bay, then we should be able to go out around the Bay in a wet year and find longfin larvae after they’ve been hatched,” he said. “If I can’t find longfin larvae in a wet year, then my hypothesis fails. This is something we can test experimentally, so part of this experiment is to go to likely locations over a number of years, but certainly in a wet year and look for longfin and see if we can find them out in the wild.”

The second element is to do an otolith analysis, which is another way at getting at a similar issue, he said. “You take longfin that you’ve netted as part of your survey; you look at their ear bones [called otoliths], put them under a spectrograph, and analyze the chemical signatures in their ear bones. … Different drainages have different chemicals in them and so if you analyze the chemical signatures, in many cases you can tell where these fish were hatched and where they grew up. It’s almost like having a very crude GPS receiver embedded in the fish which you then extract, so we’re going to be looking at some of the fish that are caught and trying to figure out where they were hatched and even if whether they were hatched in the Pacific Ocean. So that’s pretty exciting.”

The third element of the study is to look at the Otter Trawl and the Midwater Trawl and try to determine why these two different trawls are getting such dramatically different results for longfin, he said. “Our hypothesis is that because the system has been getting clearer and the turbidity has just been dropping to practically to nothing, it’s getting so clear out there that longfin are seeking darkness and that as the water gets clearer, they drop deeper in the water to try and be safe or maybe to follow their food,” he said. “Over time, they are dropping below the standard Midwater Trawl nets, but they are still caught by the bottom net, the Otter Trawl net. That’s the hypothesis that we’ll be trying to confirm or refute that by doing a number of studies designed to get at the issue of what it the vertical distribution of longfin. … This will help us understand which of the nets we should really be really relying on when we think about population and distribution and life cycle.”

Mr. Fullerton said they were starting the studies this year. Monitoring has already been expanded and they are currently doing test runs. “Basically Cal Fish and Wildlife agreed to limit some of the monitoring it had required us to do under CESA, and that freed up some money that is now funding this project so that was a creative way to get this thing funded.”

“Finally, I think this had been a good experience, and we’re having good cooperation,” he said. “We’re looking at highly leveraged theories about longfin and I’m not sure how it will come out, but potentially this could have big implications for whether longfin really is implicated by project operations or not.”

For more information …

- For the agenda, meeting materials, and webcast for this meeting, click here.

Get the Notebook blog by email and never miss a post!

Get the Notebook blog by email and never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!