At the January 27 meeting of the Santa Clara Valley Board of Directors, Charles Gardner, President and CEO of Hallmark Group Capital Program Management, gave a presentation on the planning for construction of the Bay Delta Conservation Plan’s new water infrastructure, also known as Conservation Measure 1. Mr. Gardner and the Hallmark Group were brought into the BDCP in 2009 to reorganize the program, identify budget and schedule restraints, and introduce transparent and collaboration between interested stakeholders.

At the January 27 meeting of the Santa Clara Valley Board of Directors, Charles Gardner, President and CEO of Hallmark Group Capital Program Management, gave a presentation on the planning for construction of the Bay Delta Conservation Plan’s new water infrastructure, also known as Conservation Measure 1. Mr. Gardner and the Hallmark Group were brought into the BDCP in 2009 to reorganize the program, identify budget and schedule restraints, and introduce transparent and collaboration between interested stakeholders.

Mr. Gardner said he would be talking primarily about Conservation Measure 1. “We’re not going to get into the other aspects of the BDCP, because that’s what our narrow focus is on today,” he said. “Just to make sure the people understand, there hasn’t been any decision that’s been made with respect to permitting this project. We’re still waiting for the regulators to decide that the project is permittable and get through the public comment process, and so part of our effort here is in the event that the project does go forward, we do think that it’s our fiduciary responsibility to make sure that we have an organization that’s ready to implement Conservation Measure 1, when and if the project is approved.”

He then presented a slide of the schedule. (Note: the public review period has since been extended until June 13, 2014. He noted that the first admin draft was produced in February of 2012. “On February 27, we actually delivered that admin draft on time and about $3 million under budget, and then what happened is we had a project that was not well received by the regulating agencies and we went into a major redesign of that project, and so that’s what we’ve been doing since February 27, 2012 up until December 13 of last year.”

He then presented a slide of the schedule. (Note: the public review period has since been extended until June 13, 2014. He noted that the first admin draft was produced in February of 2012. “On February 27, we actually delivered that admin draft on time and about $3 million under budget, and then what happened is we had a project that was not well received by the regulating agencies and we went into a major redesign of that project, and so that’s what we’ve been doing since February 27, 2012 up until December 13 of last year.”

The February 2012 admin draft was a 15,000 cfs facility with five intakes and a 750-acre forebay which was a pumped facility with operations projected to be somewhere right around 5.9 – 6 MAF per year. “What we wound up with after going through this redesign effort, adding some new models, doing some optimization on the engineering side, we wound up with a three-intake facility with a 40-acre forebay, with 9000 cfs capacity that was gravity fed,” he said.

“Right now we’re in the public comment period,” he said. “We’re continuing to work through getting all the public comments, so we have a concept called EGAP – Everything Goes According to Plan. We’ll be there on October 19 with a ROD/NOD, and that is if Everything Goes According to plan. That is our schedule; I do not think we have consensus on that from the regulating agencies at this point.” He also noted that if the public comment period is extended, the dates will slip as well.

“Right now we’re in the public comment period,” he said. “We’re continuing to work through getting all the public comments, so we have a concept called EGAP – Everything Goes According to Plan. We’ll be there on October 19 with a ROD/NOD, and that is if Everything Goes According to plan. That is our schedule; I do not think we have consensus on that from the regulating agencies at this point.” He also noted that if the public comment period is extended, the dates will slip as well.

He then addressed the recent stories (remember, this was January of this year) about the budget. The original budget for the first phase of planning was $240 million, he noted. “The second column is the amount of the phase that we’re currently tracking, so you can see that we were at $12.1 million projected, and we actually delivered it for about $9 million,” he said. “Then the other part of the budget that we talked about which is where we’ve been stuck for the last 656 days, the public phase, milestone 2; originally we thought that would be a quick turnaround between getting from the admin to the final. We got stuck with generally a complete redo of the project and so that’s where our dollars and our time have been spent.” The bottom line is that there is about $27.6 million in the budget to be committed, he said.

The big question is if there are enough funds left in the budget to finish the project, said Mr. Gardner. “If we go back to our October 9th schedule of this year, then the answer is yes. You can see on the top, that’s our environmental spending and on the bottom is the engineering spending. At the top, you can see that we’re in the red, so we’re expecting we’re going to need to add about another $3.4 million to complete the environmental process. That’s the bad news. The good news is that we have enough left over by our projections in the engineering budget to be able to cover that and have about $619,000 left over to complete the project. If the schedule slips much past October 9, we’re going to be in jeopardy of needing some more dollars to finish this planning effort.”

The big question is if there are enough funds left in the budget to finish the project, said Mr. Gardner. “If we go back to our October 9th schedule of this year, then the answer is yes. You can see on the top, that’s our environmental spending and on the bottom is the engineering spending. At the top, you can see that we’re in the red, so we’re expecting we’re going to need to add about another $3.4 million to complete the environmental process. That’s the bad news. The good news is that we have enough left over by our projections in the engineering budget to be able to cover that and have about $619,000 left over to complete the project. If the schedule slips much past October 9, we’re going to be in jeopardy of needing some more dollars to finish this planning effort.”

Optimization

There were a lot of concerned property owners in the Delta about the impacts of the project, he said. “We went out and met with them individually to make sure we understood those concerns,” he said. “The result of those meetings was getting a better understanding of the particular impacts on their land and their businesses that they have in the Delta. Through that process, we’ve made some very significant changes in the project. We made a big shift from the current alignment over to the east as a result of those discussions with the farmers.”

There were a lot of concerned property owners in the Delta about the impacts of the project, he said. “We went out and met with them individually to make sure we understood those concerns,” he said. “The result of those meetings was getting a better understanding of the particular impacts on their land and their businesses that they have in the Delta. Through that process, we’ve made some very significant changes in the project. We made a big shift from the current alignment over to the east as a result of those discussions with the farmers.”

There were a few other changes as well. “We had some borrow sites that were slated to be on the islands up in the north near the intakes, but the farmers impressed upon us how devastating it would be to put a borrow site on one of their islands,” he said. “We did not fully appreciate the drainage implications that it had for their islands, so one of the things that we did was we eliminated the borrow sites.”

He said that originally they had planned for a cut and cover pipeline from the intakes to the intermediate forebay. “The idea of doing a cut and cover pipeline on some of these islands destroyed their drainage, so we changed from cut and cover to going to just a bore tunnel for that part of the alignment as well.”

“A lot of this is like playing Whack-A-Mole,” he said. “You knock down one problem only to find you’ve created another one somewhere else, so while we made some really good changes for some of the farming interests, we didn’t make friends with people over on Staten Island, which is a big sandhill crane fly in area. We’ve been in negotiations and discussions with the fish and wildlife agencies and some of the stakeholders who are concerned about the impacts on the sandhill cranes and we are coming up with a plan that’s going to be acceptable to all the parties involved, and we’ll be announcing that I hope within the next month or so, once we conclude our final discussion on that.”

We spent a lot of time researching and understanding how to deal with reusable tunnel material, Mr. Gardner said. “For some reason, the tunneling industry has chosen to call this tunnel muck,” he said. “There were a series of articles that ran in the Sacramento Bee that said we were going to bury the entire Delta in tunnel muck, so we spent some time trying to understand that, we spent time with the Hetch Hetchy tunnel project, and we went to other projects to find out what these guys were doing with this tunnel material. It was largely advertised to be this toxic sludge that came up out of the ground. We’ve put out some fact sheets to debunk the myth that this is going to be some toxic material that’s going to invade the Delta and make it unfit for use.”

We spent a lot of time researching and understanding how to deal with reusable tunnel material, Mr. Gardner said. “For some reason, the tunneling industry has chosen to call this tunnel muck,” he said. “There were a series of articles that ran in the Sacramento Bee that said we were going to bury the entire Delta in tunnel muck, so we spent some time trying to understand that, we spent time with the Hetch Hetchy tunnel project, and we went to other projects to find out what these guys were doing with this tunnel material. It was largely advertised to be this toxic sludge that came up out of the ground. We’ve put out some fact sheets to debunk the myth that this is going to be some toxic material that’s going to invade the Delta and make it unfit for use.”

There is a significant amount of tunnel material that will be generated –about 25 million cubic yards, he said. It has been tested and has been found to be suitable for levee improvement, for use as a road base, or for use in restoration projects. In order to get the tunnel material to the consistency to bring it out of the ground, it is treated with certain agents. “We’ve tested these agents and they are biodegradable so we know we don’t have a toxic waste issue,” Mr. Gardner said, noting that the material will be tested as it is brought out of the ground to make sure it’s not toxic.

“By the time this project is over, based on the conversations that we’re having with people in the Delta who are interested and also people for the other restoration efforts, we think that this 25 million cubic yards of tunnel material will probably be oversubscribed,” he said. “We think there will be more beneficial uses of this material than there is material, so I expect that while right now we have in our plan that we’re just piling it up on some of the areas that are subsided on the islands where we’re going to be mining the tunnels, I suspect that there will be a lot of interest in it to move it off to some other place where it can be put to beneficial use.” He noted that 95% the tunnel material from the new Hetch Hetchy tunnel was put to use, in part for the restoration of Bear Island.

He then presented a slide with updated costs after the optimization, and he noted that the estimate is being carried in 2012 dollars.

He then presented a slide with updated costs after the optimization, and he noted that the estimate is being carried in 2012 dollars.

He then turned to the management of Conservation Measure 1. “Hope is not a strategy; we have to have a plan,” he said. “And so even though we don’t really have a project yet, we did think that it was incumbent on us to start coming up with the plan on how you might manage this tunnel effort if a project came to be. … One of the opportunities that we’ve been given with CM1 is a white sheet organization, so there is no organization for designing and constructing CM1 now.”

CM1 Management

The organization, which currently consists of a small group of engineers, has been thinking about how to structure the organization that will oversee the design and construction of CM1. “The idea is that this organization will be created exclusively to design and construct Conservation Measure 1, and when that effort is over, this organization will sunset and go away,” he said.

Mr. Gardner said they started by benchmarking and visiting a lot of different projects, some of them more than once. “One of our first projects was the Bay Tunnel project and there were a lot of great lessons that we learned from that,” he said. “We’ve been up to the Alaskan Viaduct project a couple of times. That is a design-build project basically going under the city of Seattle and to date, it is the largest soft ground tunneling project in the world at 57.5 feet in diameter. As you are aware, the tunnels that we’re proposing are 40 feet in diameter so this one is well beyond what we’re proposing.”

Mr. Gardner said they started by benchmarking and visiting a lot of different projects, some of them more than once. “One of our first projects was the Bay Tunnel project and there were a lot of great lessons that we learned from that,” he said. “We’ve been up to the Alaskan Viaduct project a couple of times. That is a design-build project basically going under the city of Seattle and to date, it is the largest soft ground tunneling project in the world at 57.5 feet in diameter. As you are aware, the tunnels that we’re proposing are 40 feet in diameter so this one is well beyond what we’re proposing.”

He noted that the tunnel boring machine, named ‘Bertha, is stuck at this point. The project was a design-build project that was going pretty well, he said. “This depends on who you talk to, whether you’re talking to the owner or you’re talking to the contractor,” he said. “The owner says we made you aware that this particular well site was in the alignment of the tunnel, and the contractor opinion on that is well you did make us aware that it was there but you didn’t tell us that it was a steel casing we were going to run into. So it will be interesting to see how this plays out. … An interesting perspective with the other issues that have arisen with that project. When this owner transferred the risk via design-build, they believed they transferred all the risk, so all the problems that are accruing to that project, they believe are the responsibility of the contractor.”

They also visited a project in Colorado Springs that at first glance, doesn’t sound like such a great comparison until you understand the politics that surround it, he said. “This is a 60” cut and cover pipeline that goes from Colorado Springs to the south, through the county and city of Pueblo to the base of the Pueblo Dam. Some of the history there – Colorado Springs has some very old water rights to water that sits in Pueblo Dam that they haven’t exercised, and now that Colorado Springs is growing, they are starting to exercise those rights. Colorado Springs is a fairly affluent community in comparison with the city of Pueblo, so the city of Pueblo thinks their water is being stolen by Colorado Springs, plus they are digging this pipeline right through the county of Pueblo so they are getting all the impacts and they are getting their water stolen. So you can see that it’s sort of a politically, not that dissimilar from some of the arguments we have up in Sacramento right now.”

The project had one of the best examples of the organization they would like to build, he said. “It was a melded organization. You could not tell when you went to visit the project who was the consultant and who actually worked for the Colorado Springs utility. … We felt like in terms of overall team work and the way that the culture had evolved on that project, it was something that we’d like to emulate. The project also had the distinction unlike a lot of these other major projects of being slightly ahead of schedule and about $100 million under budget.”

He also noted that they had looked at the Port of Miami tunnel project, Lake Mead intake #3, Combined Sewer Outflow projects, the Central Subway Project in San Francisco and other transit tunnels underway in Seattle, as well as meeting with members of the High Speed Rail Authority.

He also noted that they had looked at the Port of Miami tunnel project, Lake Mead intake #3, Combined Sewer Outflow projects, the Central Subway Project in San Francisco and other transit tunnels underway in Seattle, as well as meeting with members of the High Speed Rail Authority.

They also did case studies of other projects to see what they could learn from those, such as Boston’s tunnel project, The Big Dig. “The Big Dig was a $2.6 billion original budget, when it finished it was $14.6 billion, but that was in escalated dollars, so 55% of those dollars were just from inflation. But still when you do inflation adjusted numbers, it’s still a $6 billion bust on the budget, so not a very successful project from the standpoint of cost containment.” Other projects they studied were the Panama Canal Third Lane Locks Project, the Bay Bridge Seismic Safety Project, and the Chunnel.

Challenges

He then turned to the challenges. “Murphy was an optimist, and that’s the quote that we look at when we approach these projects is we need to be thinking defensively about how we design an organization because with these mega-projects, the dollars are really significant and when things go wrong, they seem to go really wrong and in a hurry.” So they categorized the challenges that they heard about, and then thought about how they might address them, he said.

He then turned to the challenges. “Murphy was an optimist, and that’s the quote that we look at when we approach these projects is we need to be thinking defensively about how we design an organization because with these mega-projects, the dollars are really significant and when things go wrong, they seem to go really wrong and in a hurry.” So they categorized the challenges that they heard about, and then thought about how they might address them, he said.

“The biggest challenge of course is cost overruns,” he said. Poor communication, poor risk management and changing specifications are really all actors on the same stage of cost overruns, he said. “They all contribute to cost overruns and it’s one of the things that we want to pay particular attention to as we move forward in putting the CM1 office together.”

With cost containment, the cost estimate is really  important, he said. “Everybody locks in at the first number when you put it out there that this is going to be the cost of the project and it never goes away so you have to be careful when you put that first estimate out.”

important, he said. “Everybody locks in at the first number when you put it out there that this is going to be the cost of the project and it never goes away so you have to be careful when you put that first estimate out.”

“The other thing that I don’t know that people think about is this diffusion of responsibility,” he said. “These projects take a really long time from concept to completion. … We’ve already had two governors since I’ve been on the project. By the time the project is complete, by our projection, on the EGAP method, we will have at least two and possibly three more governors that we’ll have to go through those administration changes.”

“A lot of questions get asked about how do we insure the project against not only changes in the government at the Governor’s level, but how do we guard against changes from DWR directors? And how do we guard against changes from the public water agencies?,” he said. “You have a director who is friendly to the project and his or her tenure and then this next director is not. That’s one of the things we have to spend some time thinking about is how do we keep some continuity against all these changes that are going to happen with respect to our leadership, and also this propensity to, when you come on board to a project, to say, well that didn’t’ happen on my watch and now we’re going to do something different. Then you wind up with no one taking accountability for anything that’s happened on the project, and what you have is a big mess with everybody pointing at each other so how do we guard against that? “

Another challenge is discounting the risk that’s involved in some of these projects and not being really diligent about managing your risk register, he said.

The current cost estimate is called a Class 3 estimate which means it’s based on a 10% level of design which they tried to steer it as much as possible towards being a deterministic type estimate, he said. “We hired a very top shelf estimating firm to do the cost estimate for us, and the direction that we gave them was to bid this project as if you were going to submit your bid on bid day. We wanted a real number based on real quantity takeoffs … and so that’s how we developed our estimate. We’re carrying right now about a 36% or $3.2 billion contingency in our budget.”

The current cost estimate is called a Class 3 estimate which means it’s based on a 10% level of design which they tried to steer it as much as possible towards being a deterministic type estimate, he said. “We hired a very top shelf estimating firm to do the cost estimate for us, and the direction that we gave them was to bid this project as if you were going to submit your bid on bid day. We wanted a real number based on real quantity takeoffs … and so that’s how we developed our estimate. We’re carrying right now about a 36% or $3.2 billion contingency in our budget.”

Mr. Gardner said that the there is more work to be done on the estimate, such as updating it to 2014 dollars, as well as a reference estimate where the actual costs of a similar project are used. “Part of the reason for that is that we’re saving our engineering dollars to make sure that we have enough dollars left in that original $240 million budget to finish the planning process,” he said. “That’s the top priority for us.”

The “Christmas Tree Effect” is when somebody adds something to your project that you didn’t expect, and then you get tagged with the responsibility of managing the budget for that and it becomes part of your problem and your cost overrun, he said. “A good example of that are the concessions that you might have to make politically to get a project to go forward. The Bay Bridge, for example, had a $350 million bike path that was added to it that was not part of the original cost projection and that was to get the support of the City of Oakland as I understand it. We do not have anything budgeted for the Christmas tree.”

“I just don’t think you can spend enough time on risk management,” he said. “One of the things that we see in these projects is to check the box. There’s the creation of a risk register and then you just forget about it. You went through the trouble to identify the risks, but you didn’t actually manage it, and you didn’t use it to inform your decision making.”

“I just don’t think you can spend enough time on risk management,” he said. “One of the things that we see in these projects is to check the box. There’s the creation of a risk register and then you just forget about it. You went through the trouble to identify the risks, but you didn’t actually manage it, and you didn’t use it to inform your decision making.”

Mr. Gardner said that the simple process for doing a risk assessment is to identify risks and put them into broad categories, assess the risks by probability of occurrence, calculate the costs associated with the risk, and then make a determination about how to manage those risks. “Then you rank those risks, based on the probability times the cost, and then you choose what you’re going to do with the risk. Are you going to allocate based on to the entity or party who’s most able manage that risk? That’s sort of a typical rule in risk management,” he said. “Permitting risks is one of those risks that is really hard to transfer over to another party besides the owner. Then you decide how you’re going to respond to those risks, so if that risk happens, what are you going to do about it, when and if it happens, and then you have an active program for controlling the risk. … It’s an ongoing learning process, so you take your lessons learned and you continue to use that to reinform your risk management team.”

“This is such a high priority position to us … so we’ll hire someone who’s job depends on being the very best risk manager that we can find,” he said.

In regards to safety risks, an owner-controlled insurance program or an OCIP is one way what a lot of mega-projects of this size control the safety risk, he said, explaining that’s where the owner has it’s own insurance program that covers all the contractors that are working under them on the project. “It’s a blanket insurance program. You get to define what the safety standards are going to be, you have a company that really manages those safety standards. … We had a couple presentations for people who big advocates of the OCIP insurance approach, and then we’ve had other presentations where they say you really don’t get any savings … because the contractors aren’t that sophisticated about being able to quantify their insurance costs and pull them out of the bid that you wind up having some overlap in the insurance costs and so there’s a pretty healthy debate on whether you get value on that or not.”

Best practices

They also spent time learning about the best practices, such as having a single point of accountability. “You have to have a single point of accountability for these projects, and so knowing who is responsible for what and not having a team of people who are responsible for the same thing. We have this internal working mantra that if more than one person’s responsible for it then nobody’s responsible for it so we’re all very much on point in making sure that we know who’s responsible and who’s accountable for it.”

Timely decision making is critical to the success of these projects, he said. “When this project is into construction, by our projection, it’s going to be about $3 million per day of delay, so you’re going to have to be equipped to make decisions quickly. And then that plays into the next bullet point which is the opportunity cost of time. You do have to be aware that for every day that this project is not complete, that it’s costing you more money.”

Timely decision making is critical to the success of these projects, he said. “When this project is into construction, by our projection, it’s going to be about $3 million per day of delay, so you’re going to have to be equipped to make decisions quickly. And then that plays into the next bullet point which is the opportunity cost of time. You do have to be aware that for every day that this project is not complete, that it’s costing you more money.”

Having as structured defined process or stage gates for key components of the work to make sure that they have hit all of their requisite milestones before you go to the next phase of the project is also critical for success, he said.

“Hiring contractors on value not total cost ties right into procurement,” he said. “This might be a little bit more of a wish than something that we can actually do. When you’re in the public contracting realm, you have to award to the low bidder. I think we’d very much like to have some more tools in our tool box for procurement, something like design-build, especially for tunnel projects which seems to be the way most of the big tunnel projects are going these days. … We would like to be able to do something rather than just award on the lowest price and I think some of the best practice that we saw out there is that if there’s any way you can get out of that and just award on the quality of the people that are being brought to the project, that’s a better way to move forward.”

Timely and accurate reporting is important, he said. “Because of the sophistication of all of the program management or project control software that’s out there, you could just have death by data, and so the challenge that we have is to pick the right metrics and create a dashboard that is simple in understanding and that’s informative so you don’t have to spend two weeks trying to figure out what the data is telling you and by then, you’ve already wasted the opportunity to make an impact on whatever that particular decision was.”

Design and construction enterprise

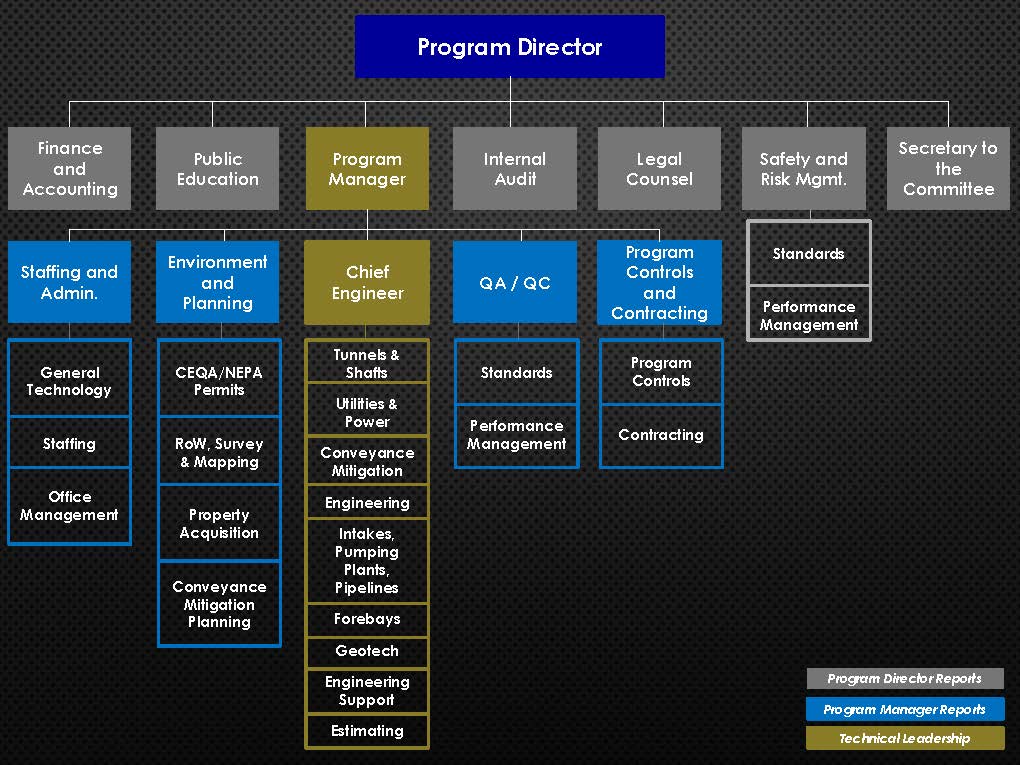

He then turned to the design and construction enterprise. “We hired McKenzie and company to go and look at what was best practice in designing an organizational structure for a project of this magnitude. So as is their practice, they had a small army of ivy league MBAs who scoured the globe to find out exactly what the very best people were doing,” he said, presenting a slide of the organizational chart. “There’s still a lot of discussion about how the report up from the program director will be managed so that is still being worked on with DWR and the public water agencies. I will say most of what happens from the Program Director down is not being discussed because it’s largely agreed to now.”

He pointed out that the organization as it currently exists consists of about six people. “There is no big organization out there; we have a blank piece of paper. We have six engineers who meet on a regular basis to discuss how are we going to implement and get this organization stood up and be ready if a project is approved to move forward, so I don’t want to put you under any misconception that there’s a whole lot of ‘they’ out there; there’s not many of ‘they’. A select group.”

He pointed out that the organization as it currently exists consists of about six people. “There is no big organization out there; we have a blank piece of paper. We have six engineers who meet on a regular basis to discuss how are we going to implement and get this organization stood up and be ready if a project is approved to move forward, so I don’t want to put you under any misconception that there’s a whole lot of ‘they’ out there; there’s not many of ‘they’. A select group.”

A single point of accountability is one of the key tenets, he said. “Ultimately the Program Director’s accountable for the success of the project. Everyone under the Program Director is accountable for the success of the their enterprise that their running, their box on the org chart, so there will be one person in charge of each of those boxes and they will be responsible for the success of their effort. We’re committed to making sure that we hire world class expertise to lead these boxes. It’s not who’s available, it’s who’s the best in class to run their respective box in the organization. We expect that we’re going to fill those boxes with a combination of individuals from DWR, the Bureau, the public water agencies and also the private sector where that experience doesn’t exist with any of the other organizations.”

This organization won’t have any employees, he said. “Everyone who serves on the organization will be serving either by an interagency agreement or just a consulting agreement or something along those lines,” he said. “The idea is that the organization is going to exist for the purpose of designing and constructing CM1 and when its over, it’s going to end. It’s not going to be an ongoing concern and we didn’t’ want to be weighed down by any HR issues.”

“One of the interesting things I learned while interviewing the different projects – the final question I would ask the program directors is, so what is it that you look for when you’re bringing people on to serve on your project? What are the characteristics of the ideal teammate? They would list things like persistence, good communication skills, great work ethic, and one of the things that they very rarely mentioned in their top five was technical ability which I thought was interesting. I always ask why didn’t you say technical ability? And they always responded with, we can teach the technical ability, we can go hire the technical ability, but these other aspects, you either have them or you don’t. So I thought that was an interesting observation.”

The most important job is going to be the program manager as they will be responsible for all of the different features, he said.

“The MacKenzie group also put together a decision chart that was pretty instructive that helps to make sure that that you make the right decision at the right point in the organization and not have every decision flow up to the top of the organization, but making sure that you made the right decision at the right time at the right level in the organization with the right report up to the organization to make sure there was communication about how a decision was made,” he said.

He then presented a slide listing the characteristics that the organization would be designed for. “Our number one is cost-control,” he said. “We want to make sure that we have clear accountability for the decisions that are made and the actions that are taken within the project. Timely effective decision making. And being a good community partner. … When it’s all over, we would like for that community to say that maybe they didn’t necessarily embrace the project but while we were there, we did an excellent job of managing their concerns while we were constructing.”

He then presented a slide listing the characteristics that the organization would be designed for. “Our number one is cost-control,” he said. “We want to make sure that we have clear accountability for the decisions that are made and the actions that are taken within the project. Timely effective decision making. And being a good community partner. … When it’s all over, we would like for that community to say that maybe they didn’t necessarily embrace the project but while we were there, we did an excellent job of managing their concerns while we were constructing.”

We’ve discussed how to reduce design changes, and we’ve talked about risk control, and how that feeds into cost control, he said. Key performance indicators will be established for every box on the org chart, he said. “The key performance indicators not only talk about just the performance of that particular job description but it also relates to the health of the job, so you could have a project that was performing really well and making all of its milestones with respect to budget and schedule, but you may have a bunch of people who are burned out and hate working there, so we want to make sure we are managing both of those, not just the performance but also the health of the organization.”

“In a calm moment, we gathered our engineers around and asked if this project was an overwhelming success, what vision would you have for us, if you could look forward to the future and have your highest aspiration, and it was this: to become a model organization for the delivery of water-related mega projects. If we did everything right, this would be an organization that people from around the globe would come to to say how’d you guys pull that off, so that’s our aspiration,” said Mr. Gardner.

“The actual mission of the organization is a bit more grounded,” he said. “We have a goal within the project which is everybody goes home safe. We want to be able to construct conveyance facility on time, again the idea that if you construct it on time, your probability of being on budget is going to go up, and if we construct it within specifications, again, the probability that the project’s going to be on budget goes up, and if we are really experts at managing risk, that feeds into being able to control the cost, and all of this is within the context of the BDCP.”

“The actual mission of the organization is a bit more grounded,” he said. “We have a goal within the project which is everybody goes home safe. We want to be able to construct conveyance facility on time, again the idea that if you construct it on time, your probability of being on budget is going to go up, and if we construct it within specifications, again, the probability that the project’s going to be on budget goes up, and if we are really experts at managing risk, that feeds into being able to control the cost, and all of this is within the context of the BDCP.”

He then presented a slide with the construction schedule, noting this was if Everything Goes According to Plan (EGAP), assuming the project gets the ROD/NOD on October the 9th,” he said. “You can see that we’re still projecting completion of the project at the end of 2027, and commissioning through 2028.”

He then presented a slide with the construction schedule, noting this was if Everything Goes According to Plan (EGAP), assuming the project gets the ROD/NOD on October the 9th,” he said. “You can see that we’re still projecting completion of the project at the end of 2027, and commissioning through 2028.”

“So with that … ”

For more information …

- Click here for the agenda and meeting materials for this meeting.

- Click here for Charles Gardner’s power point.

- Click here to watch the webcast of this meeting.