At the February 19th meeting of the California Water Commission, Department of Water Resources staff gave a highly informative presentation on the basics of water transfers, and DWR’s role in facilitating them. In this panel presentation, Maureen Sergent from the State Water Project Analysis Office addressed what a water transfer is and some of the water rights issues that water transfers are based upon, Maureen King from the Office of Legal Counsel gave a summary of major legal considerations for water transfers, and Tom Filler from the Water Transfers Office talked about some of the recent initiatives that DWR has undertaken to facilitate water transfers and address issues.

Maureen Sergent, State Water Project Analysis Office

Maureen Sergent began by saying that she first became involved with water transfers back in 1991 and has been involved in them off and on ever since. “Our understanding and evaluation of transfers has evolved significantly from that time period as we learn more about transfers, how the water supply system works, and how some of these actions affect the water supply,” she said.

Maureen Sergent began by saying that she first became involved with water transfers back in 1991 and has been involved in them off and on ever since. “Our understanding and evaluation of transfers has evolved significantly from that time period as we learn more about transfers, how the water supply system works, and how some of these actions affect the water supply,” she said.

Since water transfers can mean different things to different people, Ms. Sergent said for the purposes of her discussion, water transfers are transactions between a willing seller and a willing buyer where the seller will take certain actions to reduce the use on his property and transfer that water to a buyer downstream and shifts water from use in one place to use in another place.

Ms. Sergent said the three most common types of actions take to make water available for transfer are:

- Crop idling, where a farmer will idle some land that he would have planted otherwise, and he will transfer the water savings to someone downstream;

- Groundwater substitution, where a grower will continue to farm but pump groundwater and use that groundwater on their existing place of use, and transfer their surface water supply that they would have diverted to someone downstream;

- Reservoir reoperation, where an agency that has a reservoir and has storage rights will release more water from their reservoir than they would have to serve just their local service area.

“One of the biggest issues in evaluating a transfer is making sure that transfer is a responsible transfer, that you are not transferring water that would have otherwise been available to another user downstream of you and upstream of the new point of diversion, and that’s where most of the complication lies,” said Ms. Sergent. “We hear so much about the efforts to streamline transfers and we’re all interested in trying to do that to the extent that we can, but we have to make sure the one component that we don’t omit is an analysis to make sure what we’re transferring is not going to injure someone else in the process.”

“One of the biggest issues in evaluating a transfer is making sure that transfer is a responsible transfer, that you are not transferring water that would have otherwise been available to another user downstream of you and upstream of the new point of diversion, and that’s where most of the complication lies,” said Ms. Sergent. “We hear so much about the efforts to streamline transfers and we’re all interested in trying to do that to the extent that we can, but we have to make sure the one component that we don’t omit is an analysis to make sure what we’re transferring is not going to injure someone else in the process.”

Ms. Sergent then reviewed the key things that they look at in every transfer:

- It won’t injure another legal user of water, so another downstream user that has a legal right to water will not see less water in the watercourse than he would have if this transfer hadn’t taken place;

- It won’t unreasonable impact fish and wildlife or other instream uses; “We wouldn’t want to see a transfer that would seriously affect streamflow or water quality,” Ms. Sergent said.

- It won’t unreasonably affect the economy from where the water is coming. “This is very sensitive in Northern California. There’s a fear that if we open up the market too much, you’re going to see a drying up of the Sacramento Valley to serve other areas, so we have to be sensitive and look at that, so we do a real water determination.”

- Monitoring requirements are included in each one of the transfers to try and make sure that the transfers are responsible transfers.

“The big question is how do we determine real water? We have tried to make some improvements, and it’s a question for a lot of people who want to do a transfer. Just how much do I have to transfer?” Ms. Sergent noted that they have put together some technical guidance documents and checklists to help people with the process.

“First and foremost, you have to have a right to the water, whether it’s an individual diversion right or a diversion right under a contract, and that right has to be transferable,” said Ms. Sergent. “In most cases, except for instream flow, riparian rights are not transferable. If you have a contract, there has to be a provision or the approval of whoever you get your water from.”

“If you have an individual right, that right has to match the transfer,” Ms. Sergent continued. “You can’t have a water right to divert in the winter for say duck flood-up, and then propose to transfer water in the summer, so your water right must match what you propose to do for the transfer.”

“In a year like this, an additional challenge is that the water has to be there,” she said. “You may have a right and you may use it every year, but this year, as you are probably aware, the water board is closely evaluating various watersheds, and they are going to be issuing notices of potential unavailability. If you are operating under an individual right, and you get a notice of unavailability, there is no water to transfer, so we have to look at each one of those things and we try to structure our conveyance agreements such that if conditions change we can adapt to them.”

Every type of transfer is evaluated a little differently to determine the real water, Ms. Sergent said. “For crop idling, we need an accurate estimate of the amount of water that the crop would have consumed,” she said. “The transfer is not based on how much water is diverted, and that is a very common misconception from people who have a water right. They think I have a water right to 1000 AF; I’m not going to use it so I’m going to transfer 1000 AF. If you didn’t transfer, you might have diverted 1000 AF, but 300AF come back, and that is available to those other legal users downstream, so we have to get an estimate of what the water supply would see with and without the transfer.”

Every type of transfer is evaluated a little differently to determine the real water, Ms. Sergent said. “For crop idling, we need an accurate estimate of the amount of water that the crop would have consumed,” she said. “The transfer is not based on how much water is diverted, and that is a very common misconception from people who have a water right. They think I have a water right to 1000 AF; I’m not going to use it so I’m going to transfer 1000 AF. If you didn’t transfer, you might have diverted 1000 AF, but 300AF come back, and that is available to those other legal users downstream, so we have to get an estimate of what the water supply would see with and without the transfer.”

There are also contributions to groundwater from deep percolation that must be taken into consideration, she said. “The Sacramento Valley is absolutely interconnected, so if you transfer water that would have contributed to the water supply in one form or another, it will show up in the stream, so the common method for determining what’s transferable under a crop idling scenario is the evapotranspiration of applied water. That varies by crop, it varies by region, and it varies by cultural practices. There are a few crops that are a little more consistent. Rice being one of them, and in recent years, the majority of crop idling transfers we’ve seen have been rice. So we use averages. The only way to truly determine would be instrumentation and it just isn’t practical, so we have to make our best technical estimate. We have averages that we’ve developed and our land and water use people have looked at as well as other technical publications.”

There is a list of crops that are accepted for transfers, Ms. Sergent said, noting that not all crops that people would like to transfer are accepted. “With irrigated pasture, unfortunately, the variability in the evapotranspiration is so broad, it can go from .8 to 3 acre-feet per acre, that without instrumentation, it’s almost impossible to tell what that is,” she said. “Other crops like alfalfa, we might accept from one region but if it’s grown in the Delta, you have access to water supply and it’s almost impossible to keep it from coming back, so we look at all of those things. We look at the historical pattern of their crops because if they’ve grown tomatoes for four years in a row but then say they would have grown rice this year, it’s not likely that basing a water transfer on that would provide a realistic estimate of what the amount of transferable water is.”

“The land that is idled has to stay idled,” she said. “We conducted a demonstration project in the Delta because of the experience we had in our 1991 drought water bank so see just how much water was actually made available by idling within the Delta lowlands, this was one of the lowland islands, and the groundwater is so high and the weeds are so aggressive, that they estimated they would make 2.7 AF per acre available – they made .5. And so if you are requesting someone to move that water, that’s a huge difference in what the estimate of water is and so there are certain areas where we have to look very closely and certain areas where we might have to require instrumentation versus just an estimate of the average.”

“For groundwater substitution, we have learned that if we don’t account for the change in streamflow as a result of additional pumping, that we are transferring more water than was actually made available,” she said. “Since we recognize that the system is interconnected, we try and make an estimate of how much the additional pumping will affect the stream systems during balanced conditions when it matters. We know that if you pump groundwater, it eventually comes at the expense of surface water in one way or another, but if it comes during excess conditions, that’s good for everyone. If it comes during balanced conditions when the projects are either releasing additional water or there’s just enough water for everyone, than it’s going to come at the expense of someone else.”

“For groundwater substitution, we have learned that if we don’t account for the change in streamflow as a result of additional pumping, that we are transferring more water than was actually made available,” she said. “Since we recognize that the system is interconnected, we try and make an estimate of how much the additional pumping will affect the stream systems during balanced conditions when it matters. We know that if you pump groundwater, it eventually comes at the expense of surface water in one way or another, but if it comes during excess conditions, that’s good for everyone. If it comes during balanced conditions when the projects are either releasing additional water or there’s just enough water for everyone, than it’s going to come at the expense of someone else.”

“We have criteria on where you can put your well because that affects how strongly that well might influence the surface water,” continued Ms. Sergent. “That’s a determination of location – if its close or shallow, it has a more rapid effect than if it’s far away and deep in the aquifer parameter, so we have criteria that look at that. We also require that there be an accurate flow meter. We found that in prior transfers, some of them were off by 20%, which makes a significant difference when you’re asking someone else to move it.”

“In a reservoir reoperation, we need to know that that is going to be water that would be released that would not be released in the absence so we ask for historic records and other things to demonstrate that this is new water that wouldn’t be there otherwise,” she said. “Reservoir reoperations transfers are a little unique in that the impact to downstream users is not during the year of the transfer, but it’s in the following year. If you create a bigger hole in your reservoir because you’re releasing water you would not have, you’re going to fill up with streamflow that would have flowed downstream the following year, but for that extra hole, so we add what we call refill requirements criteria so the refilling of that hole as a result of that transfer happens at a time when others are not impacted.”

“All these go to making sure the two parties that are involved in the transfer are the ones that absorb the impacts of that transfer,” said Ms. Sergent.

Some other types of transfers that are not as common:

- Conservation transfers: On-farm conservation is a very big issue right now, she said, not noted that not all conservation measures make water available for transfer. “That’s hard for some people to understand, but if you do things like just reduce your tailwater, it may make your system more efficient, reduce your pesticide discharges and things like that, so it’s very beneficial, but if you’re cutting off the return flow, you’re cutting off water that would have been available to someone downstream so it doesn’t necessarily generate transferable water.”

- Crop shifting: This is where you might shift from corn to wheat, for example. “A higher water use to a lower water use, and that change in consumptive use savings is the transferable water. It doesn’t happen as often because the economics are not as favorable.”

- Instream dedication: This doesn’t really create new water supplies but it has some environmental benefits, and that’s the one case where riparian water rights are actually transferable, she noted.

“In many of these cases and where DWR gets involved, you need conveyance facilities to get it from the seller to the buyer, and when it has to move across the Delta, we get a request to convey that water,” said Ms. Sergent. “Water code section 1810 says that the owner of a public facility has to provide conveyance capacity if it’s available, and the Department is very interested in using the transfers to the extent possible to improve water management, but it’s limited by our capacity. Right now that capacity is constrained by so many different factors. We have our biological opinions, our water rights decision D- 1641, and so when we’re constrained during other times of the year, we have to put more of that water into the limited transfer window, which according to our biological opinions is July through September.”

“In years like this, we have lots of capacity because we’re not moving project water, but we have other things that will constrain our ability to pump water such as water quality and outflow requirements,” she said. “Our operators will make an estimate of what’s available, and requests come in to the Department, they come to the State Water Project Analysis Office and we evaluate those and develop a conveyance agreement that will have all the requirements, and the seller and the buyer are both party to those agreements.”

“We move the water July through September,” Ms. Sergent said. “It either has to be on pattern if it’s a direct diversion water, or if there’s storage available, we can coordinate with the transfer party.”

Ms. Sergent said that when you see big numbers associated with amount of transfers per year, such as 1.2 to 1.7 MAF of transfers a year, it’s not the north-to-south or willing buyer to seller where the seller takes some land out of production to move it to another one. “Most of those are intra-project transfers,” she said. “The CVP has a very active exchange program or transfer program among its contractors. It doesn’t make new water available. It’s a reallocation of what Reclamation has determined in that year that it can provide. The Department has something similar under its contracts.”

There are also inter-project exchanges, she noted. “The Department of Water Resources and the Bureau of Reclamation will allow exchanges of project supplies so that their contractors get water out of underground storage,” she said. “Some contractors may have water in underground storage that is downstream of their locations, say Semitropic. Water doesn’t flow upstream so they’ll to an exchange with a SWP contractor to get some of their water back. Those are inter-project exchanges that don’t make the pot of water bigger, but they allow a more efficient use of what’s available.”

“Our consolidated place of use petition that we recently filed is in that category,” she said. “It’s a way to have the most efficient use of existing project supplies. It doesn’t generate new project water.”

Maureen King, Office of Legal Counsel

Maureen King from the Office of Legal Counsel followed with a discussion of the legal mechanisms that apply to transfers between willing buyers and willing sellers.

Maureen King from the Office of Legal Counsel followed with a discussion of the legal mechanisms that apply to transfers between willing buyers and willing sellers.

“The legal touchstone for all water transfers is that they can’t be conducted in a manner that injures other legal users of water,” began Ms. King. “We call this the no-injury rule, and under this cardinal principle of water transfers, you can’t do it if somebody downstream is going to be negative impacted by the transfer.” She explained that this means is that you can’t transfer more acre-footage of water than you are legally entitled to transfer, which from a legal perspective, is called the real water determination. She gave the example of a crop idling transfer where only the portion of irrigation water not being used is transferable, because some of it sinks into the ground and would otherwise go to other users.

In a real water determination, if a transfer proposes to transfer more water than they are legally entitled to, it’s going to be impact someone else, so the evaluation that we do is based on a net addition of water to the downstream system, she said. Consumptive use is the key thing, and that consumptive use can be saved in a variety of ways and different types of transfers, she said. “Project agencies, both the SWP and the CVP are the last diverters in the Sacramento and San Joaquin River system,” she said. “For a real water determination, the key component is that you need to have a baseline against which you measure the savings in water, and the baseline for a real water calculation is the amount that would have been available downstream at the historic point of diversion if you had not done the water transfer.”

“The important thing is that the volume of water that is transferred can’t exceed the amount of demonstrated reduction in consumptive use, or in the case of streamflow, augmentation of the streamflow by the transferor,” said Ms. King. “Those conservation measures can happen by release from storage in the case of reservoir reoperation transfers, from crop shifting , or from groundwater substitution transfers which are a major type that we deal with in a typical dry year, as well as crop fallowing.”

The Department of Water Resources has a very limited role in transfers, she said. “We are generally not the buyer, we are not the seller of the water, nor are we the negotiator of the price per acre-footage for that water that’s going to be transferred,” she said. “When DWR conveys water for what’s known in the water code as a bona fide transferor, it’s subject to Section 1810 of the water code. Section 1810 of the water code creates a mandate that if capacity is available in the SWP system, we have to make it available to a bona fide transferor. However, this obligation is subject to DWR being able to make certain determinations regarding that specific transfer.”

Ms. King explained that a bona fide transferor is an entity that has a contract for the sale of water that is conditioned upon the acquisition of a conveyance facility to get the water from the buyer to the seller. “That’s where DWR comes in, and our legal nexus coming in there is in the legal context of a conveyance agreement which is the contractual mechanism we use,” she said. “The 1810 determinations that have to be made in order for this conveyance capacity to be available for water transfer go to both environmental and economic considerations, and they are spelled out in Section 1810(d) of the water code. And again, the no injury rule comes in here, and you have to be able to show that you’re not going to injure another legal user of water, and also that you will not unreasonably effect fish, wildlife, or other instream beneficial uses. Finally, you have to ensure that you’re not injure the economy of the area of origin from the transfer. DWR has to make written findings for the 1810 determinations in every single transfer in which they are applicable.”

She noted that these determinations needed to be made even on certain one-year or temporary transfers, even if they are exempt from CEQA. “If we are going to wheel the water, they are subject to these environmental and economic considerations,” she said.

“Typically long-term water transfers are defined as transfers that span more than one year and are subject to CEQA; the seller of the water is typically the lead agency under CEQA, and DWR as the conveyor and the buyer are responsible agencies,” said Ms. King. “Short term water transfers of less than a year of post-1914 water rights are exempt from CEQA under Section 1729 of the water code, but as I just pointed out, even though they don’t get CEQA, they do get the 1810 review.”

“Short term transfer of pre-1914 water rights are subject to CEQA, and again seller is typically the lead agency and DWR the responsible one,” she said. “The CEQA in the case of most of these one-year transfers takes the form of an initial study and a negative declaration.”

Ms. King explained that there is a pre-1914 and post-1914 divide in water law that is a jurisdictional issue that goes back when the water code and the water board as it exists today was established in 1914 and did not bring in preexisting water rights into the board’s jurisdiction, so they are typically – not completely, but typically exempt from most water board jurisdiction. She noted that both pre and post 1914 water rights are subject to the 1810 determinations if the use of DWR’s conveyance facilities is sought.

“It’s worth noting that in case of pre-1914 rights, common law also imposes some restrictions,” she said. “There’s a no injury concept in common law that would apply to those.”

“In summary, the transfer of post 1914 water rights get State Water Board and DWR review if our conveyance facilities are used – if we wheel the water,” she said. “Pre 1914 water transfers are not subject to the water board review, but they are subject to CEQA and common law, and any water transfer that’s conveyed by DWR for the SWP facilities is predicated upon DWR being able to make the requisite 1810 findings about the environment and the economy. Finally I wanted to add the both CESA and ESA apply to the participants in the water transfer, particularly to the seller who has most of the information about the conditions around where the water is found.”

Tom Filler, Water Transfer Office

Tom Filler from DWR’s Water Transfer Office then updated the Commission on the status of some of the near-term and long-term actions that DWR is taking to help facilitate water transfers.

Tom Filler from DWR’s Water Transfer Office then updated the Commission on the status of some of the near-term and long-term actions that DWR is taking to help facilitate water transfers.

“DWR is taking the initiative to implement management actions to facilitate water transfers as directed in the executive order B-21-13, the California Water Action Plan, and more recently, the Governor’s drought proclamation,” he began. “With those requirements, we are moving forward. We are also meeting with buyers and sellers and other various state and federal agencies to help coordinate in the facilitation of transfers.”

Mr. Filler said they are working on improving contracting procedures for transfers that are dependent upon State Water Project facilities, facilitating or fast-tracking water transfers with appropriate supporting documentation for 2014, and improving coordination and alignment with other agencies, both state and federal. DWR has also updated the information on the website, including updated outreach tools and graphical data detailing water transfer data from 2012-2013. “It is important to note that we’re doing all we can to help facilitate transfers in this very dry year,” said Mr. Filler.

“We’re working in coordination with both the State Water Board and the Bureau of Reclamation on a clearinghouse approach so we can have a one-stop shop to where people can look at formal transfer proposals that have come in, and get updates on what’s happening in the transfer world,” he said. “That’s still in development at this time but we hope to have something up pretty soon.”

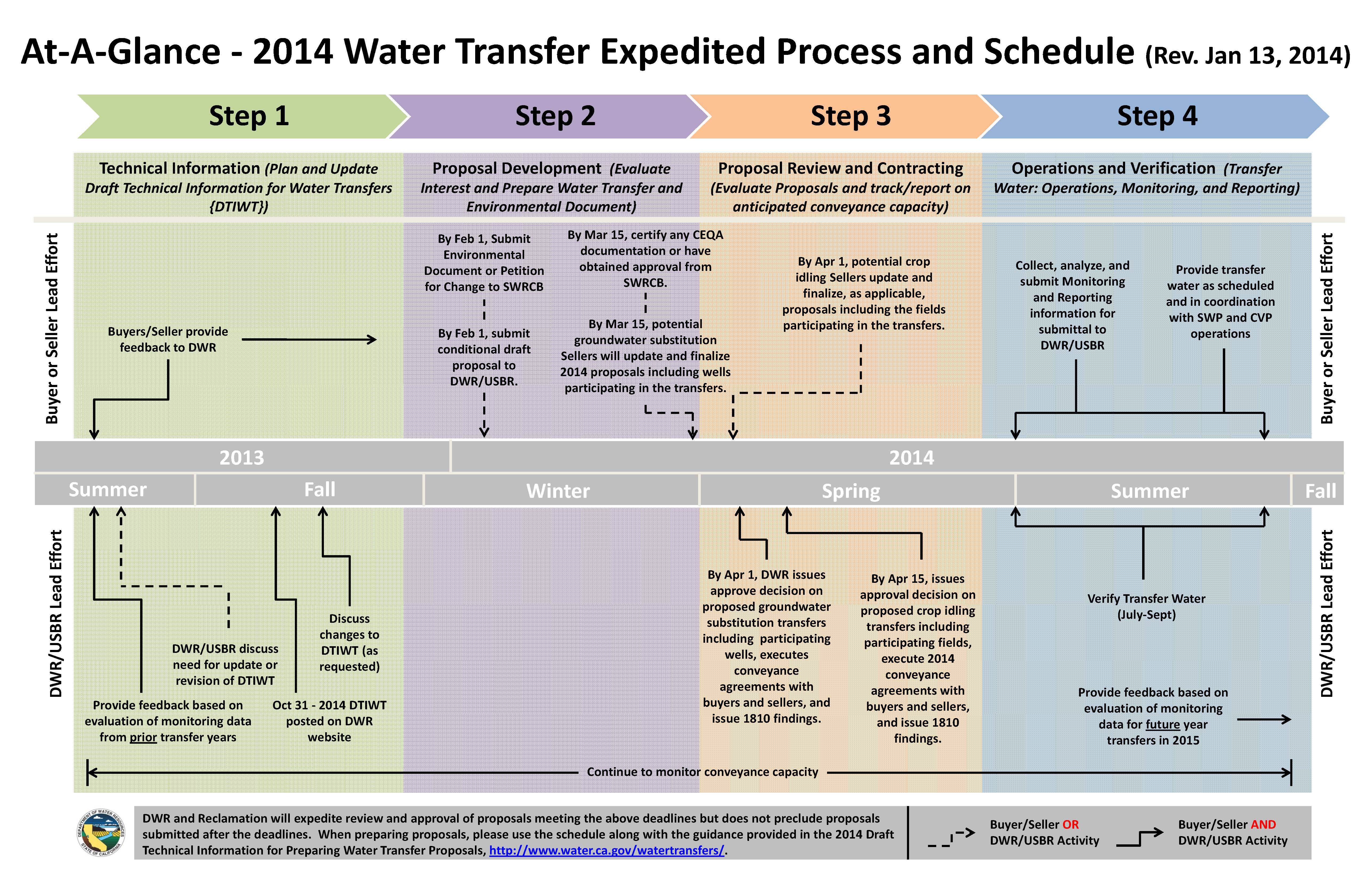

There is a 2-page handout which describes DWR’s role in water transfers, as well as some of the near and long-term actions they are tacking. “A lot of those actions came out of recommendations that we obtained during meetings with the buyers and sellers and other agencies,” said Mr. Filler. He also noted that they have developed an ‘at a glance’ process and schedule that breaks out the process into the four steps of preparing technical information, proposal development, proposal review and contracting, and then operations and verification.

“Recently, due to the extreme nature of this year, we revised the process and schedule to provide additional opportunity for transfer proponents to submit their proposals early for review,” he said, noting that to date, they had received a lot of inquiries, but no formal proposals. They are also going to expedite any transfers similar to transfers approved in 2013, and they have not made any changes to the technical information requirements, so they are the same as last year.

“We’re also accepting wells that were previously approved by DWR for groundwater substitution transfers,” said Mr. Filler. “If they were approved between the window of 2009-2013, the transfer participants this year do not have to do any additional work. This may not hold true for future years, but for 2014, due to the critical nature, we thought it would be a good idea just to help transfer proponents in their preparation.” He also noted that the streamflow depletion factor for groundwater substitution transfers will remain the same as 2013.

Long-term, they will continue their outreach efforts with stakeholders to improve transparency, as well as work on website improvements. “For the technical, operational and administrative rules, we want to continue to improve those efficiencies for the internal review process, the contracting process, and water transfers, operations, and verification methods in any way that we can,” he said. “We’ll be working with folks, both the agencies and buyers and sellers, to improve that over time.”

They will continue to develop and periodically update the technical guidance for the different types of water transfers: crop land idling, groundwater substitution, and reservoir reoperations. “I think it’s important that we continue that work in refining the work for each one of those transfers to get a real idea and understanding of how much water is being generated when it comes to specific transfers,” he said.

They will continue to develop and periodically update the technical guidance for the different types of water transfers: crop land idling, groundwater substitution, and reservoir reoperations. “I think it’s important that we continue that work in refining the work for each one of those transfers to get a real idea and understanding of how much water is being generated when it comes to specific transfers,” he said.

“Currently the Bureau of Reclamation is working in coordination with San Luis Delta Mendota Water Authority in developing a long term environmental document, and we’re coordinating and cooperating with them in the development and research and providing them with information with some of the studies that we’ve doing recently to help them improve their document,” he said, adding that they are also working with local agencies such as Butte County and others to address any concerns they may have for transfers originating out of their areas.

“We’re going to continue to the develop tools and our analytical capabilities to better determine the transfer capacity and timing to give a better understanding and reduce the uncertainty,” he said. “Over the course of time as our tools get better, people will have a better idea of whether there will be capacity available or not to actually move transferred water,” noting that there is a lot of constraints on transferred water can be moved as well as competition for that capacity.

“Estimating the amount of water that might be available this year has really been tricky because of the potential for curtailments and we’d like to have a better handle on evaluating that in the future if we can,” he added.

DWR will continue to develop the tools and analytical capabilities to better determine transfer capacity, evaluate system water management information, and improve transfer management, he said. They were also working on developing a policy guidance process document for step-by-step guidance, as well as breaking out the technical guidance documents for each type of major type of water transfer, and providing that technical information separately in different documents.

For more information …

- Click here for Maureen Sergent’s power point.

- Click here for Maureen King’s power point.

- Click here for Tom Filler’s power point.

- Click here for the Water Transfers page at DWR.

- Click here for background data regarding transfers during 2012-2013.

- Click here for a fact sheet on water transfers.

- Click here for the agenda, meeting materials and webcast for this meeting.

See also …

- Water transfers at the California Water Commission, part 1: An overview of California’s Transfer Market and DWR’s activities related to transfers

- California’s Water Market: By the Numbers, Update 2012, PPIC Report