Water transfers can be an effective way to address shortages and add flexibility to the system, especially in dry years, but the process has often found to be cumbersome and the requirements often changing. Recognizing the importance of transfers, the Governor’s emergency drought proclamation included provisions to streamline and expedite transfers.

Water transfers can be an effective way to address shortages and add flexibility to the system, especially in dry years, but the process has often found to be cumbersome and the requirements often changing. Recognizing the importance of transfers, the Governor’s emergency drought proclamation included provisions to streamline and expedite transfers.

Accordingly, the California Water Commission has taken an interest in water transfers, hearing presentations at two recent meetings. At the November 20, 2013 meeting, the Commission heard from Ellen Hanak, Senior Fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California who gave an overview of California’s water transfer market, and Gary Bardini from the Department of Water Resources who discussed DWR’s activities related to water transfers. The basics of water transfers best described as “Water Transfers 101” were covered at the February 19, 2014 meeting, coverage which will be posted tomorrow.

Ellen Hanak, Public Policy Institute of California

Ellen Hanak began by saying she would be drawing on research regarding water transfers that the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) has been doing on an ongoing basis with the most recent report on water markets and groundwater banking published in November 2012.

Ellen Hanak began by saying she would be drawing on research regarding water transfers that the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) has been doing on an ongoing basis with the most recent report on water markets and groundwater banking published in November 2012.

Water markets are temporary long-term or permanent trades of water use rights, usually in exchange for compensation; transfers can be in the form of leases for just one year which is legally a temporary trade, longer term leases, or permanent transfers, Ms. Hanak explained. Groundwater banking refers to purposefully storing surface water in aquifers in wet years for use in dry years, and she said she’ll be talking specifically about a specific subset where water it is more of a market operation because people are storing water for third parties.

Water markets and groundwater banking are important new tools for California especially for drought management, which is especially true for groundwater banking because groundwater storage is a great way of getting us through droughts, Ms. Hanak said. The water market can also be a useful tool for drought management, and has been more so in certain times in our recent past than in others.

These tools can also help in accommodating long term shifts in demand, she said. “Water trading is an important aspect, because most of the water in California has been allocated a long time ago to somebody or another, and the economy has shifted in ways that mean that it makes sense to move some of that water into some of the other growing regions and growing sectors,” she said. “For example, a lot of our early water rights were developed by the mining industry which is a lot smaller now and doesn’t need as much water as it used to, so water markets can facilitate long term shifts in use in exchange for compensation for the folks who developed those water rights to begin with, and may have made investments in relation to that.”

These tools will be useful for adapting to climate change and will help us deal with the expected variability and reduced snowpack that is anticipated, Ms. Hanak said.

You can’t think about a water market the way you think about a market for widgets, she pointed out. “There are ways in which a lot of conditions have to be in place for it to work, and that’s true also for groundwater banking,” said Ms. Hanak. “You have to have the infrastructure to be able to get the water from one place to another, and for groundwater banking, you have to specifically have some local infrastructure as well to be able to get the water in, get it out again, and then get it to the people who are going to be using it. You also have to think about protections in both of these cases.”

You can’t think about a water market the way you think about a market for widgets, she pointed out. “There are ways in which a lot of conditions have to be in place for it to work, and that’s true also for groundwater banking,” said Ms. Hanak. “You have to have the infrastructure to be able to get the water from one place to another, and for groundwater banking, you have to specifically have some local infrastructure as well to be able to get the water in, get it out again, and then get it to the people who are going to be using it. You also have to think about protections in both of these cases.”

“One of those is that you shouldn’t be able to sell somebody else’s water,” said Ms. Hanak, explaining that when water is applied to a field, not all of it is consumed by the crop; there are portions that seep into the groundwater basin or return to the river. “If the person who was selling water was able to sell every drop that they applied to the field, they would be ending up selling some water that somebody’s going to be using downstream – it’s already claimed for, so that’s a protection against third parties.” She noted that it’s also important to think about instream flows and what is needed for fish and wildlife protection as well. “The state has some good protections compared to some other places in the world that have water marketing in relation to some of these third party issues, but it maybe imperfect on the groundwater side, related to the fact that there’s not comprehensive groundwater regulation in California.”

“For groundwater banking, you have to be sure that you are protecting the people who are putting water into the bank account so that they are able to get their water again when they put it in, and also you want to make sure that they aren’t taking somebody else’s water out of the bank, so good bank management requires good monitoring and accounting,” she said.

Preventing local economic harm is a different from making sure you’re not taking someone else’s water, she said. “Even if the water counting is all done right, certain kinds of water marketing can change economic activity in an area,” she said, pointing out that land fallowing can lead to other impacts such as reduced local economic activity, employment impacts, and smaller local tax revenues. “State law requires some consideration to that, but it doesn’t require that absolutely no economic harm be done, but I think in responsible transfers, especially when these are large, long-term transfers, the onus is on them to make sure that that is minimized.”

California has enviable infrastructure compared to most anywhere else for developing a water market, she said, presenting a map of California’s water infrastructure. “This system basically allows you, when it’s working well, somebody in the far north of the system at the top of the Sacramento Valley can sell water to somebody down near the border of Mexico, in San Diego,” she said. “In most other states in the west, you cannot do this. In Australia, you can’t do this.” She noted that the map on the right show the counties that have had water market activity over the past couple of decades.

California has enviable infrastructure compared to most anywhere else for developing a water market, she said, presenting a map of California’s water infrastructure. “This system basically allows you, when it’s working well, somebody in the far north of the system at the top of the Sacramento Valley can sell water to somebody down near the border of Mexico, in San Diego,” she said. “In most other states in the west, you cannot do this. In Australia, you can’t do this.” She noted that the map on the right show the counties that have had water market activity over the past couple of decades.

“Here’s the infrastructure map again with a spotlight on the Delta,” she said. “It’s a big piece of our infrastructure for getting water from the wet places to the dry places in this state – the demand centers both urban and agricultural. It goes through that Delta which is a fragile hub from an infrastructure perspective, not just the issue of reliability if there’s an earthquake, but right now the ability to move water at various times of the year because of environmental restrictions. That’s become a big issue for the water market in recent years,” noting that the Delta is important not only for north-south transfers, but also for some east-west transfers as its often the best way to get water across the valley to the west side.

“Here’s the infrastructure map again with a spotlight on the Delta,” she said. “It’s a big piece of our infrastructure for getting water from the wet places to the dry places in this state – the demand centers both urban and agricultural. It goes through that Delta which is a fragile hub from an infrastructure perspective, not just the issue of reliability if there’s an earthquake, but right now the ability to move water at various times of the year because of environmental restrictions. That’s become a big issue for the water market in recent years,” noting that the Delta is important not only for north-south transfers, but also for some east-west transfers as its often the best way to get water across the valley to the west side.

Many rural counties have enacted ordinances restricting groundwater exports. Ms. Hanak explained that in the 80s and early 90s, a lot of counties became concerned about their groundwater being sent elsewhere, so they put groundwater export restrictions in place. “What they do is say you can’t export without a permit and we want to make sure it’s not going to cause local harm, but they don’t do anything about making sure that there’s not local overdraft happening,” she said. “There are some differences in degrees to the extent to which they are applied, but they tend to apply specifically to direct groundwater exports, but also groundwater substitution transfers where if you’ve got surface water and groundwater rights, and you can sell your surface water and pump more. That’s considered a transfer that would be subject to approval by the county.”

Many rural counties have enacted ordinances restricting groundwater exports. Ms. Hanak explained that in the 80s and early 90s, a lot of counties became concerned about their groundwater being sent elsewhere, so they put groundwater export restrictions in place. “What they do is say you can’t export without a permit and we want to make sure it’s not going to cause local harm, but they don’t do anything about making sure that there’s not local overdraft happening,” she said. “There are some differences in degrees to the extent to which they are applied, but they tend to apply specifically to direct groundwater exports, but also groundwater substitution transfers where if you’ve got surface water and groundwater rights, and you can sell your surface water and pump more. That’s considered a transfer that would be subject to approval by the county.”

There’s no comprehensive source of data on water transfers, Ms. Hanak said. For their research, they used data from state, federal and local sources, so it includes transfer between different water districts or with state and federal agencies, but she noted that it doesn’t include trades within a water district between farmers, or trades among agencies within a wholesale area such as Metropolitan, but it does give a broad sense of the statewide water market.

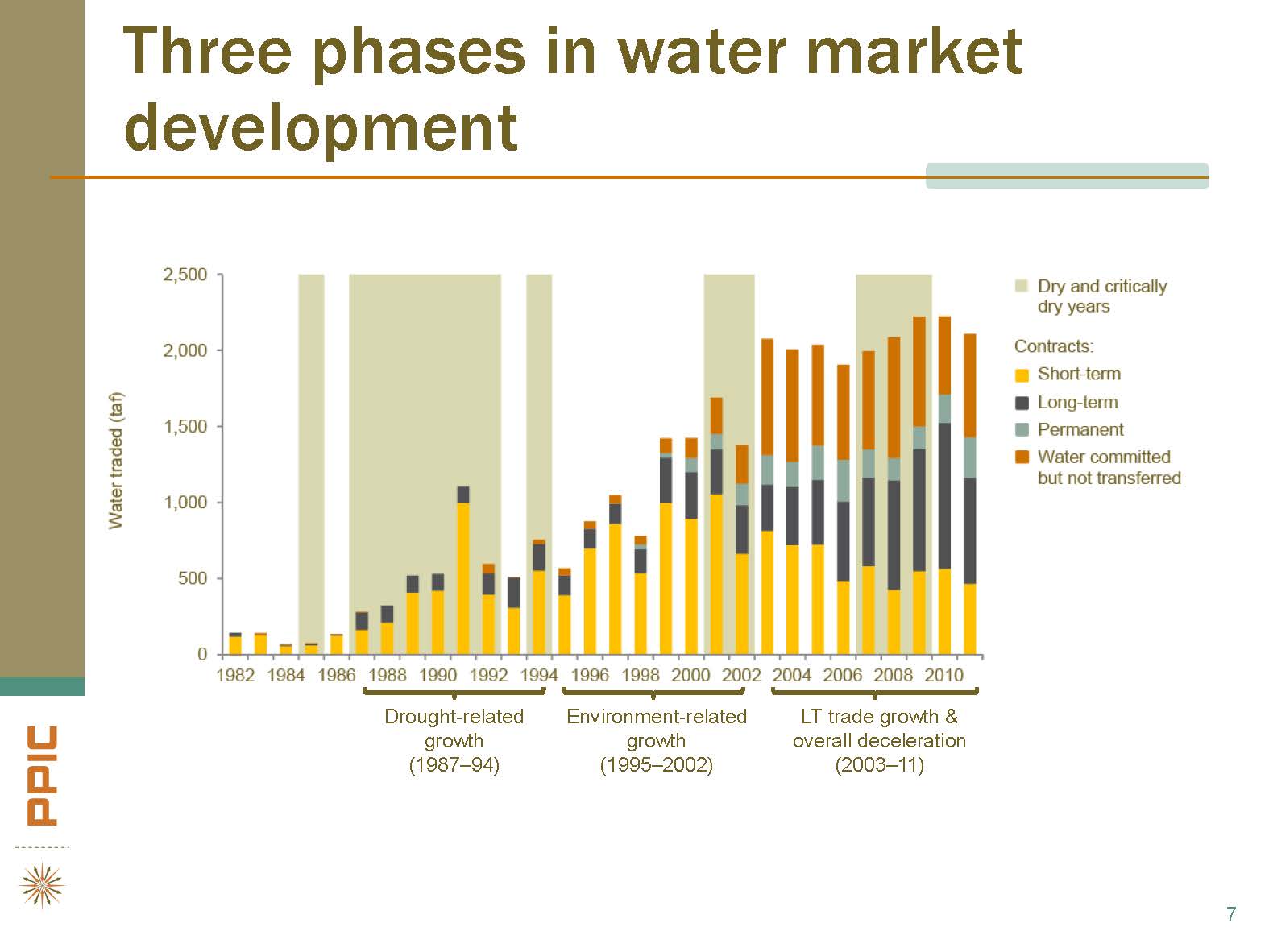

She then presented a graph depicting water market activity since 1982. The development of the water market can be divided into three phases, she explained. The first phase was during the big drought in the 80s to the early 90s; the state was heavily involved and in 1991, started the drought water bank. During the second phase, the market continued to grow especially because of environment related actions, due to direct purchases to support environmental programs as well as the enactment of the CVPIA. The third phase, the most recent, is characterized by more long-term and permanent transfers, as well as an overall deceleration, she said.

She then presented a graph depicting water market activity since 1982. The development of the water market can be divided into three phases, she explained. The first phase was during the big drought in the 80s to the early 90s; the state was heavily involved and in 1991, started the drought water bank. During the second phase, the market continued to grow especially because of environment related actions, due to direct purchases to support environmental programs as well as the enactment of the CVPIA. The third phase, the most recent, is characterized by more long-term and permanent transfers, as well as an overall deceleration, she said.

She then presented a slide that depicted the different types of transfers that have occurred during each phase. She noted that the first phase was mostly short-term transfers – about 80% were single year deals. During the second phase, the market continued to grow with more short-term and long-term transfers and some permanent transfers, she said. During the most recent period, there was growth in long-term transfers especially related to the Colorado River transfers, as well as a lot of long-term and permanent transfers in the Central Valley.

She then presented a slide that depicted the different types of transfers that have occurred during each phase. She noted that the first phase was mostly short-term transfers – about 80% were single year deals. During the second phase, the market continued to grow with more short-term and long-term transfers and some permanent transfers, she said. During the most recent period, there was growth in long-term transfers especially related to the Colorado River transfers, as well as a lot of long-term and permanent transfers in the Central Valley.

“We’re now facing a situation where the short term market is actually barely bigger than it was back in the late 80s and early 90s and the long-term and permanent market is much more important,” said Ms. Hanak. There is a shift in demand and the market is coming into play here, she noted. “This is where it’s happening. It’s especially going to cities who need it to support new development, it’s also going to high value farm operations on the west side, and it’s also going to some environmental uses where some long term deals are made for that.”

The market didn’t do so well helping out with the most recent drought, said Ms. Hanak, presenting a graph showing transfers for each year and noting to ignore the orange on the top of the bars as that represents the amount that was available in the contracts but wasn’t transferred. “The total amount transferred barely went up during the drought,” she said. “We estimate probably in all, between 2007-2010 maybe 500,000 – 600,000 AF of drought related water was made available. … A very different picture than going back to the 80s early 90s drought where what the market was doing was making dry year water available. This is partly related to Delta infrastructure constraints and the difficulty getting water through, it’s partly related to other institutional issues, including very complex frequently changing approval process for getting water approved, especially north to south.”

The market didn’t do so well helping out with the most recent drought, said Ms. Hanak, presenting a graph showing transfers for each year and noting to ignore the orange on the top of the bars as that represents the amount that was available in the contracts but wasn’t transferred. “The total amount transferred barely went up during the drought,” she said. “We estimate probably in all, between 2007-2010 maybe 500,000 – 600,000 AF of drought related water was made available. … A very different picture than going back to the 80s early 90s drought where what the market was doing was making dry year water available. This is partly related to Delta infrastructure constraints and the difficulty getting water through, it’s partly related to other institutional issues, including very complex frequently changing approval process for getting water approved, especially north to south.”

She then presented a slide which depicted transfers broken down by region and by phase. “You would expect the Sacramento Valley to be a net exporting region,” she said. “It still is but way less. … The San Joaquin Valley has become a net exporting region for the water market. There is a lot more east-west trading within the valley too, it’s the most active region in the market. Southern California is importing more, mostly from the San Joaquin Valley.”

She then presented a slide which depicted transfers broken down by region and by phase. “You would expect the Sacramento Valley to be a net exporting region,” she said. “It still is but way less. … The San Joaquin Valley has become a net exporting region for the water market. There is a lot more east-west trading within the valley too, it’s the most active region in the market. Southern California is importing more, mostly from the San Joaquin Valley.”

Environmental water trades have been important in the early 2000s with the water going to the environmental water account, wildlife refuges, Salton Sea mitigation, and San Joaquin eastside flows. “That amount is also going down now because most of that has been bond funded, or state and federal taxpayer funded, so without new money for that, it’s not going to be able to continue,” she said. “We think it’s actually a useful part of the overall program for environmental management to combine regulations with market purchases.”

Environmental water trades have been important in the early 2000s with the water going to the environmental water account, wildlife refuges, Salton Sea mitigation, and San Joaquin eastside flows. “That amount is also going down now because most of that has been bond funded, or state and federal taxpayer funded, so without new money for that, it’s not going to be able to continue,” she said. “We think it’s actually a useful part of the overall program for environmental management to combine regulations with market purchases.”

Groundwater management and storage is dealt with differently throughout the state, she said. Some are formally adjudicated, and others have informal systems. “Some people dealt with the overdraft problem by getting these management systems in place and then bringing in the water and getting to some sort of sustainable level,” she said. “There are a lot of informal systems like that; the Kings River maybe is more that kind of a system; they are using price incentives and voluntary management. There are some semi-formal arrangements, especially in Kern County, where folks have set up a formal banking system where they are working for third parties, even though they don’t have a completely adjudicated or specially managed district.”

Groundwater management and storage is dealt with differently throughout the state, she said. Some are formally adjudicated, and others have informal systems. “Some people dealt with the overdraft problem by getting these management systems in place and then bringing in the water and getting to some sort of sustainable level,” she said. “There are a lot of informal systems like that; the Kings River maybe is more that kind of a system; they are using price incentives and voluntary management. There are some semi-formal arrangements, especially in Kern County, where folks have set up a formal banking system where they are working for third parties, even though they don’t have a completely adjudicated or specially managed district.”

Groundwater banks were very useful during the recent drought, Ms. Hanak said, presenting a slide showing the amount stored in groundwater banks since 1994. She pointed out how the graph shows the amount in storage increasing right before the last drought, and then drops. “Close to 2MAF were made available through these banks alone during the last drought, so three times more than what the water market was able to do in terms of drought relief,” she said, noting that there were some conflicts in Kern County which is hopefully leading to some good discussions about that.

Groundwater banks were very useful during the recent drought, Ms. Hanak said, presenting a slide showing the amount stored in groundwater banks since 1994. She pointed out how the graph shows the amount in storage increasing right before the last drought, and then drops. “Close to 2MAF were made available through these banks alone during the last drought, so three times more than what the water market was able to do in terms of drought relief,” she said, noting that there were some conflicts in Kern County which is hopefully leading to some good discussions about that.

A number of the recommendations in the PPIC report overlap with both the ACWA and the state’s water action plan, she said. The PPIC report recommends:

- Addressing infrastructure gaps: “This is important for the market and for groundwater banking.”

- Make the institutional process more consistent, transparent and predictable: “This relates specifically to DWR and the Bureau – they have a draft set of guidelines that are constantly in draft and constantly changing and often changing at the last minute for any given year.”

- Strengthen local groundwater management: “That is going to help with all both marketing and banking.”

- Develop tools to mitigate local economic impacts: “I think there are some useful experiments underway in Southern California on this.”

- Pursue more environmental transfers: “This means finding a way to pay for that, too – it could come from fees and it does come from fees in some cases already.”

- Engage high-level leaders who can take needed risks and break through barriers: “This is needed because ultimately some of this stuff is risky, and in order to take risks you have to be at the top of your organization because job of folks at the middle level is not to get their agency sued.”

Discussion highlights

“It is fascinating that the San Joaquin Valley that suffers from groundwater overdraft is a net exporter of water,” said Commissioner Del Bosque. “I’m guessing it has to do with economics – have you looked into how and why that’s happening?”

“Not net exporter of water in total, but through the water markets,” clarified Ms. Hanak. “And yes, it’s economics. Some places that are becoming somewhat marginal for agriculture have made water available, and some of that was part of the Monterey Agreement, but some of it happened since then. The concern that has been raised with some of the more recent transfers is making sure that it’s not robbing Peter to pay Paul in the sense of folks then switching to groundwater instead of their State Water Project water, and if you don’t have a comprehensive groundwater management system in place in your County or in your basin, who is to say why, if I’m a landowner, I can’t use my groundwater … ?”

Commissioner Delfino said that one of the recommendations is creating environmental water, but there have been challenges with this in the past, especially with the environmental water account and level 4 refuge water. “Given some of the concerns lately about raising money for environmental water, how do you propose to fix those problems?” she asked.

“Some of the issues that you raise are problems for any kind of environmental flows, whether its regulatory action or water that’s purchased for that use,” said Ms. Hanak. “Figuring out how we get it to where we want it to be and managing it well. The review that was done of the EWA determined that we kind of spread ourselves too thinly with it and if there had been focus on any particular objective, it probably would have had a much bigger biological payoff. … There are costs for environmental water whether we purchase it or whether it’s a regulatory cutback, and I think we need to think about that as part of the overall process of managing our aquatic ecosystems in a balanced and responsible way. One sees the price tag may be more when one is going out on to the market to purchase it then if it’s felt by farmers who are having to cut back on their activity. I think that going forward, it makes forward to have some flexibility through some dollars that can be used by environmental managers in addition to whatever is determined form the regulatory side. … I think money can help make things more palatable if used in combinations with regulations in California and I think the bright spot of the CVPIA is that’s money that been purchased with a surcharge on water users, so it is money that is there, it’s just a question of where do you put those dollars, which are still scarce, relative to the ecosystem needs.”

Gary Bardini, Department of Water Resources

Gary Bardini began by presenting a slide showing the overall amount of water transferred from 1995 to present, noting that transfers are becoming more of a regular occurrence rather than just in the dry years.

Gary Bardini began by presenting a slide showing the overall amount of water transferred from 1995 to present, noting that transfers are becoming more of a regular occurrence rather than just in the dry years.

Mr. Bardini said we had a below average 2007-09, but a very wet 2011. “It was what you’d call a really good water year because we topped everything off and moved a lot of water, but even with that, we came into 2012 water year, we still had again below average runoff. Allocations were given that were basically below the historical that we would have seen over the last 20 years coming into our first year of a dry period with 65% of SWP and the federal folks with variations below 40 and 50%.”

“Last year, it rained and then it stopped,” he said. “We called this in the 90% exceedance which is a 1% chance to have as dry of a spring that we had, and of course allocations of the water projects were very low. These were the kind of levels we’d normally see in the fourth year of a drought and you’re seeing this in the second, so it created a lot of transfer activity on the short term market that we normally wouldn’t see. Most of it in the groundwater substitution because of this trend, which really compressed the schedules and it caused a little bit of angst in the community.”

“Last year, it rained and then it stopped,” he said. “We called this in the 90% exceedance which is a 1% chance to have as dry of a spring that we had, and of course allocations of the water projects were very low. These were the kind of levels we’d normally see in the fourth year of a drought and you’re seeing this in the second, so it created a lot of transfer activity on the short term market that we normally wouldn’t see. Most of it in the groundwater substitution because of this trend, which really compressed the schedules and it caused a little bit of angst in the community.”

The cross-Delta water transfers, the north-to-south, really are just a fraction of the overall transfer market – only about 300,000 acre-feet, said Mr. Bardini, he said, presenting a slide depicting the amount of cross-Delta transfers proposed as well as where the water originated from. “A lot of it is coming from the Yuba, but you can see that there’s a pattern that the transfers that are more on the SWP system or the Feather are generally doing transfers between other State Water Project contractors, and then the Feds are doing the same; they’re generally working more and more within their service areas in the transfers.”

The cross-Delta water transfers, the north-to-south, really are just a fraction of the overall transfer market – only about 300,000 acre-feet, said Mr. Bardini, he said, presenting a slide depicting the amount of cross-Delta transfers proposed as well as where the water originated from. “A lot of it is coming from the Yuba, but you can see that there’s a pattern that the transfers that are more on the SWP system or the Feather are generally doing transfers between other State Water Project contractors, and then the Feds are doing the same; they’re generally working more and more within their service areas in the transfers.”

The Department of Water Resources has been working on the California Water Action Plan, with the Bureau of Reclamation, and also with buyers and sellers, he said, noting that they held a meeting with buyers and sellers to address some of the concerns. The issues have been grouped into 5 basic workplan items:

- Statewide management of water transfers and outreach: Prioritizing the technical issues, handling cumulative impacts, having a single point of contract, and multi-agency review teams: “These are major items heavily articulated in the California Water Action Plan, but the buyers and sellers were not as concerned on this one.”

- Technical, operational, and administrative rules: Items include refining the transfer schedule, improving outreach, creating technical guides and template agreements, and other actions to simplify the process: “A universal concern is how do we prepare better technical information and guides and how do we simplify the process, that theme is consistent among all the recent efforts.”

- Water management assessments: Crop land idling, groundwater substitution transfers, and acceptable wells for groundwater transfers: “This is a huge issue with the buyers and sellers. This is the aspect of how do you handle land idling, and how do you account for the water in groundwater substitution or what’s a good well, a lot of the implementation details. These are heavy issues with the buyer and seller community.”

- Environmental local ordinance considerations: Consider long-term document to cover sellers north of Delta: Mr. Bardini said that they have been working with the Bureau on this. “How we would do this and how do you move from short term, long term, and how do you properly address local ordinances.”

- Operational system transfers: “The big issue that we’re trying to move to is our web transfer management.”

Mr. Bardini then presented a graph titled “Short Term Improvements: Process Streamlining.” “Essentially our process is set up into four major steps,” he said. “The question is how do we provide technical information to feed the process, how is the proposal development done, more importantly how do we streamline step 3 in our efforts of doing proposal review, and then how do we handle the operational issues and the verification. These are the major things we’re looking to make improvements on.”

Mr. Bardini then presented a graph titled “Short Term Improvements: Process Streamlining.” “Essentially our process is set up into four major steps,” he said. “The question is how do we provide technical information to feed the process, how is the proposal development done, more importantly how do we streamline step 3 in our efforts of doing proposal review, and then how do we handle the operational issues and the verification. These are the major things we’re looking to make improvements on.”

We want to create a standardized conveyance agreement, Mr. Bardini said. “The Department has certain water code authorities over how we do our storage conveyance agreements, essentially making sure there’s no injury in the transfers and again, we’re trying to simplify the language and get consistency. What happened last year is that every seller attorney had their own ideas of what the language ought to be and that helped slow down the process, so we’re looking to have those conversations more up front in the process.”

Work continues on the issues surrounding groundwater substitution, Mr. Bardini said. “One issue is the trend in groundwater … you can see the changing groundwater that’s occurring throughout the Central Valley, and other areas already, and more importantly, the aspects of how you do transfers and how close you are to a river, as there’s an aspect of stream depletion. … There is some analytical work that is required, and this is one that we continue to progress on.”

Work continues on the issues surrounding groundwater substitution, Mr. Bardini said. “One issue is the trend in groundwater … you can see the changing groundwater that’s occurring throughout the Central Valley, and other areas already, and more importantly, the aspects of how you do transfers and how close you are to a river, as there’s an aspect of stream depletion. … There is some analytical work that is required, and this is one that we continue to progress on.”

He then presented a slide depicting estimated groundwater pumping in the Sacramento Valley, noting that transfers represent a small fraction of groundwater use.

He then presented a slide depicting estimated groundwater pumping in the Sacramento Valley, noting that transfers represent a small fraction of groundwater use.

For the long-term, we need to re-look at our guidance documents, he said. “My view is that we need to restructure our entire process and what I mean is that we need to separate what I call the policy guidance or what’s required in process, and the technical part related to groundwater substitution/land use or how you do system storage for transfers. … I’d like to see us start moving to handbooks as we’ve done this in the past. Providing handbooks to assist agencies is different than giving guidance or technical information.”

In terms of long-term management improvements, Mr. Bardini said, “We have a system of data collection, forecasts, river forecasts, coordinated all the way down to what I call water delivery forecasts and scheduling. These systems we’ll continue to progress and ultimately move towards a transfer management website to help facilitate transparency.”

In terms of long-term management improvements, Mr. Bardini said, “We have a system of data collection, forecasts, river forecasts, coordinated all the way down to what I call water delivery forecasts and scheduling. These systems we’ll continue to progress and ultimately move towards a transfer management website to help facilitate transparency.”

Lastly, the Department is looking to appoint a single point of contact that can be used internally as well as externally in alignment during emergencies and crisis.

“In conclusion, the Department will continue to consult with the Board and the Bureau over the state Water Action Plan and continue to align our workplans accordingly,” said Mr. Bardini.

For more information …

- Click here for Ellen Hanak’s power point.

- California’s Water Market: By the Numbers, Update 2012, PPIC Report

- Click here for Gary Bardini’s power point.

- Click here for the meeting agenda and webcast.