Deputy Executive Officer Dan Ray began by explaining that the focus of today’s briefing would be on the impacts of the BDCP on the Delta, noting that how the project would affect the Delta as a place hasn’t really been discussed much yet. “We’re charged with trying to pursue the coequal goals and the BDCP attempts to do this as well, but we’re supposed to do it, the law reminds us, in a way that protects and enhances the unique values of the Delta as an evolving place,” said Mr. Ray. “It’s evolving, it’s not locked in time, it needs to change, but as that change occurs, we want to make sure that the core thing that have made the Delta such a wonderful place to live and to visit and to farm are not destroyed.”

Deputy Executive Officer Dan Ray began by explaining that the focus of today’s briefing would be on the impacts of the BDCP on the Delta, noting that how the project would affect the Delta as a place hasn’t really been discussed much yet. “We’re charged with trying to pursue the coequal goals and the BDCP attempts to do this as well, but we’re supposed to do it, the law reminds us, in a way that protects and enhances the unique values of the Delta as an evolving place,” said Mr. Ray. “It’s evolving, it’s not locked in time, it needs to change, but as that change occurs, we want to make sure that the core thing that have made the Delta such a wonderful place to live and to visit and to farm are not destroyed.”

Those values include the landscape itself, the rural heritage, the agricultural economy, the unique land use mix of agriculture and natural resources, it’s smaller communities and larger vibrant cities, it’s unique cultural tradition and great opportunities for tourism and recreation, and the EIR is going to provide us insights on how the BDCP might change those, he said. The EIR reviews impacts and suggests mitigation measures for ways those impacts can be avoided or reduced. CEQA and NEPA require that the options to reduce or avoid those impacts be assessed, and at the state level, measures that can reduce or avoid those impacts must be adopted, if feasible.

“That’s one of the important questions that the DFW and DWR and perhaps the Council, should the project be appealed, will need to struggle with,” said Mr. Ray, noting that what is normally feasible and capable of being accomplished in a reasonable period of time, while taking account of finances and economics and social considerations and legal issues in a project of this scale is different than regular routine land use decisions. “We have a 50-year project that’s going to cost tens of billions of dollars and involves the legal and social impacts and the technological complexity that the BDCP does, what’s feasible might be a little different than in the normal context, so we wanted to make sure that you had a chance to hear from the BDCP staff and their EIR consultants at this stage of the process.”

Laura King Moon, Chief Deputy Director

Department of Water Resources

Now that the public draft is finally out, this is real opportunity to start to discuss what the impacts are to the Delta, began Laura King Moon. “We don’t want to sweep them under the rug and I think the EIR/EIS does a good job of explaining where there are going to be impacts,” she said.

Now that the public draft is finally out, this is real opportunity to start to discuss what the impacts are to the Delta, began Laura King Moon. “We don’t want to sweep them under the rug and I think the EIR/EIS does a good job of explaining where there are going to be impacts,” she said.

When the project was started seven years ago, everyone knew it wasn’t going to be easy. “We’ve had a lot of conversations with many people in the Delta about how this will affect them and we’ve tried to make adjustments already,” she said. “There are still a lot of impacts, though. We see this now as the beginning point. We’ll have lots of public comment meetings and we’ll be hearing more about what the impacts are and the concerns about those impacts.”

The hardest part is identifying what can be done about those impacts, and those conversations often have to take place in other venues, said Ms. Moon. “I’m hoping that the Council can help with that. I think you have an important role to play.”

Cassandra Enos, Senior Program Manager for the EIR/EIS

Department of Water Resources

While it’s a significant milestone to get to the public draft, it is more like the beginning, not necessarily the end, began Cassandra Enos, Senior Program Manager in charge of the EIR/EIS. “There’s still a lot of work to do and that really does involve the Delta community, very much so,” she said.

Ms. Enos acknowledged there are a lot of impacts; 615 categories were evaluated for impacts, with about 50 impacts that are listed as significant and unavoidable, most of them in the Delta. “Some of those are significant and unavoidable because they require us to have agreements with the Delta communities and other agencies to work together and find ways to mitigate,” she said, “and so because those agreements aren’t in place yet, we cannot say that this impact is avoided, but we have every hope and anticipation that we’ll be able to do that.”

Ms. Enos acknowledged there are a lot of impacts; 615 categories were evaluated for impacts, with about 50 impacts that are listed as significant and unavoidable, most of them in the Delta. “Some of those are significant and unavoidable because they require us to have agreements with the Delta communities and other agencies to work together and find ways to mitigate,” she said, “and so because those agreements aren’t in place yet, we cannot say that this impact is avoided, but we have every hope and anticipation that we’ll be able to do that.”

Besides the impacts, there are also a lot of benefits to the community, she pointed out. “There will be additional construction-related employment which will bring a lot to the Delta economy,” said Ms. Enos. “We also have ecosystem benefits; improving the ecosystem is definitely a benefit to the Delta community, and fisheries is a huge part of the Delta. My son’s an avid fisherman, he loves the Delta, so certainly we on a personal level feel like it’s very important to do what we can to preserve the character and the recreation in the Delta.”

The project has been moved further to the east, more activities have been shifted onto state-owned property, and the alignment for State Route 160 was changed in response to concerns from Delta Residents, she said. “We’ve started the conversation and we will continue that,” said Ms. Enos.

Steve Centerwell, Project Manager for the EIR/EIS

ICF International

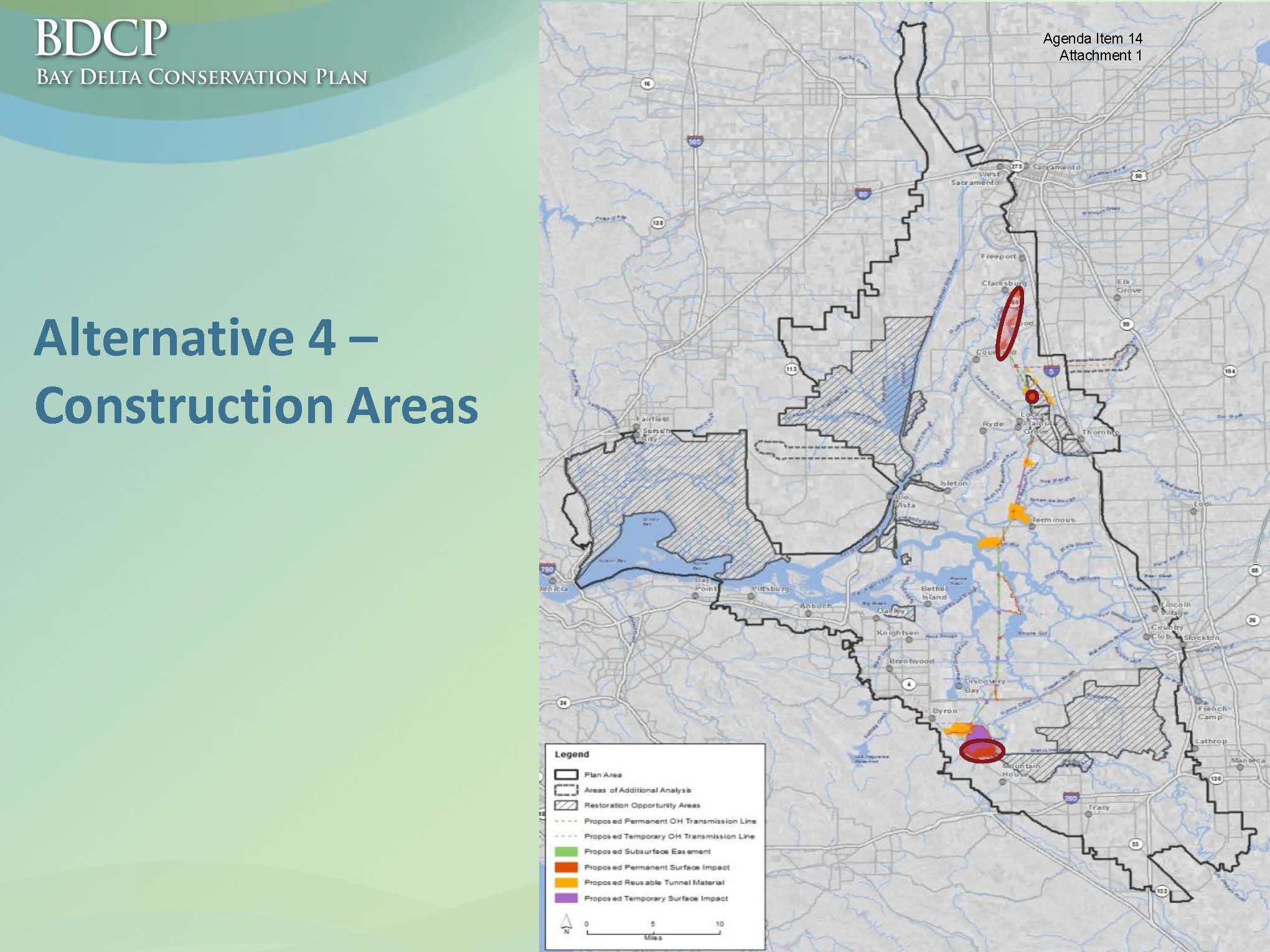

Steve Centerwell, ICF International’s project manager for the BDCP EIR/EIS, then briefed the council on the BDCP’s impacts. Most of the construction effects of the project are for the conveyance facilities, known as Conservation Measure 1, he said. The construction activity will occur in the area of the three intakes on the eastern bank of the Sacramento River between Clarksburg and Courtland, the intermediate forebay which would be just north of Twin Cities Road, the expansion of Clifton Court Forebay, and in between those points, the construction of the 40-foot diameter tunnel that will be bored from the northern location to the southern location, with tunnel boring machine shafts and vent shafts along the way.

Steve Centerwell, ICF International’s project manager for the BDCP EIR/EIS, then briefed the council on the BDCP’s impacts. Most of the construction effects of the project are for the conveyance facilities, known as Conservation Measure 1, he said. The construction activity will occur in the area of the three intakes on the eastern bank of the Sacramento River between Clarksburg and Courtland, the intermediate forebay which would be just north of Twin Cities Road, the expansion of Clifton Court Forebay, and in between those points, the construction of the 40-foot diameter tunnel that will be bored from the northern location to the southern location, with tunnel boring machine shafts and vent shafts along the way.

The majority of the effects are going to happen in Sacramento County, he said. “There’s a cluster of construction that happens at the intakes and at the intermediate forebay and for tunnel boring machine launching sites that are going to cluster some of the construction impacts there,” he explained. “There will be another large construction area in the southern portion of the plan area at Clifton Court Forebay. In between, the construction effects are going to be lighter; there will be less effect along the tunnel alignment. So I wanted to offer you that and give you the facts about where these impacts are actually going to occur.”

Transportation impacts

The effect of construction on air quality can increase criteria pollutants such as carbon monoxide, reactive organic gases, and dust. Mr. Centerwall said the entire construction footprint would cause substantial increases in these pollutants, so project on-site measures will be implemented such as electrifying equipment, making sure the equipment runs well, and other standard measures that are taken to reduce air quality emissions. “In addition, there was off-site mitigation to basically offset any of the additional emissions that we couldn’t reduce to a net zero, and that’ really the bottom line for air quality,” he said. “We’re going to reduce it to a net zero.”

Mr. Centerwall said they are aware that construction-related traffic is a big concern, so they looked at the potential effect of construction traffic in construction zones and along haul routes, as well as the level of service and the volume capacity ratio to identify areas where effects would occur in the Delta if there was a lot of construction traffic. They also considered pavement issues, where pavement may need to be improved or roadways widened to improve access.

Mr. Centerwall said they are aware that construction-related traffic is a big concern, so they looked at the potential effect of construction traffic in construction zones and along haul routes, as well as the level of service and the volume capacity ratio to identify areas where effects would occur in the Delta if there was a lot of construction traffic. They also considered pavement issues, where pavement may need to be improved or roadways widened to improve access.

The areas where construction effects would occur based on the traffic analysis are portions of State Route 4, much of State Route 12, State Route 113, and a major roadway from West Sacramento into the Delta. “All in all, there’s going to be 36 separate segments, not roadways, but 36 segments out of 114 that were evaluated that we think could be an issue in terms of capacity,” he said. “What we’ve recommended in the EIR to mitigate the effects include implementing a traffic management plan to make sure that we’re managing the construction traffic in a way that is least detrimental to residents in the Delta.”

“We’re going to also identify places where we would limit construction or times of the year or times of the day when construction might be eliminated or reduced to try to reduce effects, particularly during harvest periods when there may be a lot of farm equipment on roadways,” said Mr. Centerwall. “We want to make sure there are no conflicts there.” He said they would also be working with local transportation agencies to find ways to fix capacity issues and improve pavement condition, both before construction happens and after construction happens.

There are no plans to build a new bridge to cross channels, Mr.Centerwall said. If there are bridge crossing issues for tunnel boring machine parts or large construction vehicles, other means would be used, such as using barges.

Visual impacts

Visual impacts were also analyzed. There is an extensive appendix that identifies all the different areas evaluated and includes simulations that show what some of the major features would look like from a public view. Mr. Centerwall acknowledged that there could be significant visual impacts, so a standard list of mitigation measures were applied, such as screening of sensitive resources, moving construction areas I needed, or landscaping. “What we came up with is that we didn’t think we could completely rule out any significant impact, so we’ve concluded that that would be a significant unavoidable impact as one of our unavoidable effects during construction,” he said. “During the long term, the Department is looking at ways to improve the aesthetics of the buildings.” He presented some slides that were examples of how industrial structures can be made to look like other buildings in the area, such as a treatment plant designed to look like a barn, or a water supply plant that looks like a residential structure or other buildings in the area to make it blend into the surrounding environment better.

Reusable tunnel material

Regarding the tunnel material, Mr. Centerwall said that although the boring of the tunnels will significantly reduce the surface impacts of a canal, it will instead create millions of cubic yards of material that will need to be stored on the surface. There could be visual, land use and agricultural impacts related to the storage sites, he acknowledged, but the Department has made an environmental commitment to reuse the material. “Right now in the EIR, we identify the impact as permanent because we didn’t have a specific plan for where we would put the material or where we could use it, and so the impacts particularly on agricultural resources are elevated because we’ve identified it as a permanent impact,” he said.

Regarding the tunnel material, Mr. Centerwall said that although the boring of the tunnels will significantly reduce the surface impacts of a canal, it will instead create millions of cubic yards of material that will need to be stored on the surface. There could be visual, land use and agricultural impacts related to the storage sites, he acknowledged, but the Department has made an environmental commitment to reuse the material. “Right now in the EIR, we identify the impact as permanent because we didn’t have a specific plan for where we would put the material or where we could use it, and so the impacts particularly on agricultural resources are elevated because we’ve identified it as a permanent impact,” he said.

We’re optimistic that we’ll be able us reuse the material, and environmental commitments in Appendix 3-B spell out how it would be managed, he said. “I think everybody can agree there’s going to be a large amount of material, so the management plan really focuses on how we might reuse it, some of the options for reusing that material, and if it is reused and relocated some place, what would we do with those storage areas,” said Mr. Centerwell. “We’re talking about restoring them, maybe providing recreational amenities or other aesthetic amenities to reduce the effect of that storage area once it is moved.”

The material could be used for restoring subsided sections of islands or as levee material. “We’re going to evaluate the tunnel material first. If it’s hazardous, we’ll ship it to an appropriate landfill site; if it’s not hazardous, then it will be assessed for what the material contents are to figure out if its usable for restoration sites, for levee building or improvements, or possible construction areas; maybe flood fighting material as well, so those are just a few of the ideas. We’re looking at other ideas on how we might be able to reuse the material.”

The material could be used for restoring subsided sections of islands or as levee material. “We’re going to evaluate the tunnel material first. If it’s hazardous, we’ll ship it to an appropriate landfill site; if it’s not hazardous, then it will be assessed for what the material contents are to figure out if its usable for restoration sites, for levee building or improvements, or possible construction areas; maybe flood fighting material as well, so those are just a few of the ideas. We’re looking at other ideas on how we might be able to reuse the material.”

Ms. Enos described what testing had been done so far to evaluate the material. “We have a limited number of cores of geotech analysis that has been done along the alignment,” she said. We did take samples from each of those cores and we mixed it with the types of foaming materials that they use in these tunnel boring machines. We acquired foams from three different companies and our soils lab mixed that with the core samples that we have, and the preliminary results have shown that all of the material is suitable for engineering reuse as fill material.”

“The engineers are very excited, apparently,” Ms. Enos continued. “We also see no limitations with respect to using it for restoration or for ag. The only issue with ag is that it would need to be fertilized because the material is so far down that it doesn’t have a lot of organic materials in it. But so far, all the tests have been very positive. SFPUC was able to reuse 98%, and the only materials that they found that they couldn’t reuse because there was naturally occurring asbestos in the rock they had gone through, so there was nothing from the additives themselves that caused the material to be unusable.”

Noise

Mr. Centerwell then turned to the subject of noise, saying that they looked for the potential for construction and operational noise effects near construction sites and along construction roads, and determined most of the noise impacts would be in Sacramento County near the intakes and intermediate forebay where there is a higher concentration of residences and other sensitive land uses such as parks and schools. The noise impacts are drastically reduced farther to the south and to the west, he noted.

Mr. Centerwell explained that for the purposes of analysis, a 60 decibel threshold was used during the daytime, which is a fairly low threshold that is roughly equivalent to the noise of a loud office environment, and at night, a 50 decibel threshold was used, which is the typical background noise in a suburban area. “The mitigation is essentially trying to reduce the noise impact from construction machines including pile drivers and large construction equipment at the site, and then also to identify and implement a noise complaint program so that we can identify where noise is a particular issue and then try to resolve that issue,” he said. “The noise impacts were identified as significant and unavoidable because of the intensity of construction in some areas of the construction zone.”

Mr. Centerwell explained that for the purposes of analysis, a 60 decibel threshold was used during the daytime, which is a fairly low threshold that is roughly equivalent to the noise of a loud office environment, and at night, a 50 decibel threshold was used, which is the typical background noise in a suburban area. “The mitigation is essentially trying to reduce the noise impact from construction machines including pile drivers and large construction equipment at the site, and then also to identify and implement a noise complaint program so that we can identify where noise is a particular issue and then try to resolve that issue,” he said. “The noise impacts were identified as significant and unavoidable because of the intensity of construction in some areas of the construction zone.”

Ms. Enos added that the noise mitigation and complaint program is an example of how they intend to be proactive by having the program in place before construction activity begins. “Our intent is certainly not to wait until we hear back from somebody that they have a problem that something is noisy or bothering them, but to be out there ahead of time addressing these problems proactively,” she said. “This is something we intend to do not just with noise, but with other things, such as groundwater impacts.”

Groundwater impacts

“We did groundwater analysis related to construction and operation for the construction effects related to dewatering along the construction alignment at major facilities, intakes, the intermediate forebay, Clifton Court Forebay, and we’ve identified mitigation measures for groundwater that are intended to make sure we monitor ahead of time,” said Mr. Centerwall. “We’ve set in monitoring wells before construction happens so we can be proactive if there is a potential effect on a well facility, and then the measure goes on to say that we’ll work with that landowner to reduce the effects by bringing in water sources or deepening their well, whatever the condition entails.”

There are some operational effects related to the construction of the intermediate forebay and at Clifton Court, such as seepage into groundwater that could affect drainage in the vicinity, he said. “We’re going to identify monitoring wells around that site and also be proactive to make sure we are not affecting adjacent property owners drainage issues,” said Mr. Centerwall.

There are some operational effects related to the construction of the intermediate forebay and at Clifton Court, such as seepage into groundwater that could affect drainage in the vicinity, he said. “We’re going to identify monitoring wells around that site and also be proactive to make sure we are not affecting adjacent property owners drainage issues,” said Mr. Centerwall.

Mr. Centerwall then presented a slide that showed where the major dewatering effects would occur at the northern intakes. “The maximum that we’re talking about is about a minus 40 foot elevation change in groundwater; a lot of the wells are much deeper than that and perhaps would not be affected,” said Mr. Centerwall, “but this is based on computer modeling.” Additional areas which would experience dewatering effects would be around the construction of the intermediate forebay, the jog in the pipeline alignment, and the area of Clifton Court Forebay that is going to be expanded, he noted.

Agricultural resources

There has been an extensive review of the potential effects of conveyance facilities and restoration actions on agricultural resources. Construction of the new facilities could permanently impact 5000 acres, of which 3200 acres are used for the storage of tunnel material. “The priority for the Department is to reuse that material and to try to reduce that, so our hope is that 5000 acre number will go down substantially as we have more certainty about where we might be able to reuse that material,” he said. He also noted that 1300 acres would be impacted temporarily during construction.

The conservation plan envisions ambitious large amounts of habitat restoration in the Delta and those restoration areas will, in some cases, have an effect on agricultural lands, he said. “We haven’t estimated how much area could be affected precisely because the plan doesn’t identify specific restoration areas; it identifies restoration opportunity zones, but what we do know is that the restoration that will occur as part of the project that could potentially affect agricultural is about 80,000 acres of habitat – that’s tidal restoration, riparian, grassland, and vernal pool restoration activities,” he said. “We don’t think that’s going to be 80,000 acres but it will be some percentage of that total that could affect important farmland in the Delta, and so that’s really the tradeoff that the plan is presenting to everyone is improving habitat and conditions for covered fish and wildlife species, with some effect on agricultural resources in a plan area that’s about 740,000 acres.”

There are also direct effects on farming effects, such as salinity and primarily in the western and southern portion of the Delta, he said. “In areas where salinity is already an issue, it’s going to be an issue under this program and may be a little bit worse based,” acknowledged Mr. Centerwell. He also noted that there could be disruptions to drainage and irrigation facilities.

There are also direct effects on farming effects, such as salinity and primarily in the western and southern portion of the Delta, he said. “In areas where salinity is already an issue, it’s going to be an issue under this program and may be a little bit worse based,” acknowledged Mr. Centerwell. He also noted that there could be disruptions to drainage and irrigation facilities.

The modification to the Fremont Weir will also increase the frequency and duration of inundation of the Yolo Bypass, which will provide habitat and food sources for covered species, but also will impact agricultural operations , particularly rice farming, he said.

Mitigation measures include avoiding and minimizing impacts where possible, creating agricultural easements, and implementing the agricultural stewardship program.

Recreation resources

The project will not eliminate any park or other recreation area as part of construction or other restoration actions, Mr. Centerwell said. However, he did say that there will be some effects in the Cosumnes River preserve on Staten Island and in the vicinity related to tunnel boring machines, and some effects on fishing activity at Clifton Court Forebay.

The plan includes benefits for recreation, Mr. Centerwell pointed out. “In CM11, we’ve added opportunities to enhance recreation in the Delta,” he said. “There are opportunities around 65,000 acres of Delta preserved lands to provide trails, picnic areas, trailheads, viewing areas, and that kind of thing. Conservation Measure 11 details what the options are for recreation.” He also noted that Conservation Measure 13 would reduce aquatic weed growth in certain areas of the Delta, which would improve boat access.

“The construction that will occur in the water will not result in any closures,” said Mr. Centerwell. “The construction is going to be phased so that there’s not need for a closure. On the Sacramento River, there’s no chance that boating would be closed but there would be likely a boating speed restriction in construction areas and barge landing sites … Anything where there might be a safety concern related to boating has been restricted.”

“The construction that will occur in the water will not result in any closures,” said Mr. Centerwell. “The construction is going to be phased so that there’s not need for a closure. On the Sacramento River, there’s no chance that boating would be closed but there would be likely a boating speed restriction in construction areas and barge landing sites … Anything where there might be a safety concern related to boating has been restricted.”

The operable barrier on Old River near the San Joaquin River would be constructed so that the channel is not closed off to boating, he added.

Mitigation measures include funding efforts to carry out the recommendations of the Delta Protection Commission in its Economic Sustainability Plan and funding for the Department of Boating and Waterways to reduce aquatic weed issues, he said.

Archaeological resources

There would be about 10 archaeological resources and nine historic structures that could be affected, both directly and indirectly, he said. Mitigation measures include standard measures such as doing additional surveys to clarify where the resources are, developing recovery plans and developing treatment plans for those resources.

There are some benefits, too

The EIR identifies a number of beneficial effects, certainly in chapter 11 and chapter 12, Mr. Centerwell said. “There are beneficial effects identified for fish and wildlife species with habitat creation,” he said. “We’re going to minimize the effects of a conveyance by tunneling, which is going to substantially reduce the surface impacts. To agriculture resources, it could be a threefold difference between a canal and a tunnel, so 5000 acres for agricultural land could be 15,000 or 20,000 acres a canal. There are mitigation measures that we think will result in improved roadways; there will be jobs that will be created as part of the construction and operation of the project, there will be a need for up to around 200 people for operating the facility and then maintaining it and all the various maintenance activities, and there could be increased economic activity related to barging activities that could affect the port of West Sacramento and potentially the Port of Stockton.”

So in conclusion …

Mr. Centerwell said after reviewing the conservation plan and the environmental documents, to then review Appendix 3-B, the environmental commitments. “It is a fairly long list of commitments that the Department has made to build into the project, so it’s really not discretionary,” he said. “They are really saying it is also part of the project to do all these activities to reduce effects.”

Mr. Centerwell said after reviewing the conservation plan and the environmental documents, to then review Appendix 3-B, the environmental commitments. “It is a fairly long list of commitments that the Department has made to build into the project, so it’s really not discretionary,” he said. “They are really saying it is also part of the project to do all these activities to reduce effects.”

Now that the draft document has been released, the project enters the public input phase. “We’re really honestly looking forward to in terms of getting input on how we did with our environmental analysis and how we might be able to improve it and how we could improve the project as well,” he said. “The Department is committed to making sure they continue to look at ways to reduce effects on Delta residents.” He noted that the EIR is a project level document for Conservation Measure 1, the new conveyance facilities, and program level for the remaining conservation measures, so they will need additional environmental review. “So there will be opportunities for individual restoration projects, for example, to review and identify mitigation measures for specific projects that could help reduce the effects,” he said.

Melinda Terry

Central Valley Flood Control Association

North Delta Water Agency

During public comment, Melinda Terry spoke on behalf of the Central Valley Flood Control Association and the North Delta Water Agency about the impacts to the Delta. She began by noting that one of the things the Delta Plan talks about is improving water quality to protect the ecosystem, and the plan identifies six significant and unavoidable impacts to water quality alone. “There are 750 impacts total in the EIR/EIS, and 48 are unavoidable according to the list that the Bureau gave us,” she said.

A lot of the mitigation is conditioned on whether it’s feasible or whether it’s cost effective, so it’s discretionary, she said. “They have a lot of discretion to decide whether that’s really their project or not.”

There’s pile driving happening at 25,000 strikes a day near the intakes, and the dewatering around the shafts along the tunnel alignment that occur every 3 miles will produce a lot of noise. “You’re talking pumps that can pump anywhere from 30 to 10,500 gallons according to the EIR, and they are placed every 50 to 75 feet. So it’s not just potential noise from even pile driving; that’s a lot of noise and air quality issues as well.”

She reminded the Council of their mandate given to them in the Delta Reform Act to protect the values that make the Delta unique. Agriculture is one of the ways the Delta is unique, said Ms. Terry. “The peat soils are often talked about as a bad thing in terms of subsidence, but from an agricultural farming standpoint, it is fantastic and it makes the Delta unique,” said Ms. Terry. “The reason is that it has two really good properties. One is that it’s dark brown and it actually holds in heat; that allows them to have a longer harvesting period than any other area in the state, and they actually can then plan their harvesting based on markets that other areas cannot do.”

She reminded the Council of their mandate given to them in the Delta Reform Act to protect the values that make the Delta unique. Agriculture is one of the ways the Delta is unique, said Ms. Terry. “The peat soils are often talked about as a bad thing in terms of subsidence, but from an agricultural farming standpoint, it is fantastic and it makes the Delta unique,” said Ms. Terry. “The reason is that it has two really good properties. One is that it’s dark brown and it actually holds in heat; that allows them to have a longer harvesting period than any other area in the state, and they actually can then plan their harvesting based on markets that other areas cannot do.”

The soil is also very water absorbent, so ‘passive watering’ is used. “When it’s time for irrigation, you fill the ditch and because we have a shallow groundwater level in the Delta, that just raises the groundwater a little bit more so it touches the roots, so it’s very passive, low water intensive watering, and as the root sucks that up again the ditch will drain and you just put a little more water in and it passively will continue to water,” Ms. Terry said. “If you are dewatering these very large areas where all the facilities are going to go and the alignment and forebays – that’s lowering the ability to do that kind so that will change the watering and irrigation practices that will have to occur. They will have to do some kind of surface watering and that may be more water intensive.”

The mitigation of water supply impacts is to try and find another water supply, but the documents admit that it may not be sufficient to meet the land uses of that property, said Ms. Terry. “This dewatering is going to occur for six years at least, and so that’s a long time to either to be asked not to farm essentially. … So it’s kind of conditioned. You might get replaceable water but you might not. And it’s a really long period. … The EIR/EIS is very clear that you get abandonment of businesses and homes, and I didn’t really hear in the presentation anything about that.”

Regarding water quality, there are six constituents there that affect agriculture and our municipal intakes, and they are going to increase the costs, she said. “The environmental commitments document that was mentioned – it’s 28 pages long. They haven’t’ flushed out what they will commit to you, just that something that will be committed to try and address those. It’s really difficult for anyone to then determine okay, I’m going to read this impact, and they are promising to do something. Unfortunately, we are operating in an area where there isn’t a lot of trust, so that’s part of the problem.”

“A lot of the construction is 24/7 and even the daytime, they plan on going until ten o’clock at night, and that’s not normal for most construction sites,” continued Ms. Terry. “The noise is going to be a lot on people. … The geology and soils chapter makes it clear that we may have additional subsidence and sinkholes that are created because of that dewatering that I described. Now you’ve got a void, if you will, being created, plus we have ground vibrations from pile driving – those are some of the issues that we’ve raised from a flood standpoint too that are concerning.”

Councilmember Ruhstaller asks about the effect on land values. Abandonment is mentioned in several chapters and the loss of property value is one of the reasons, responded Ms. Terry. “It shouldn’t be a case where people are forced to abandon their homes and they have to sue to get compensation. Frankly being in the footprint is really better, in my opinion, because at least I know I’m getting paid; there’s an actual process and it’s not discretionary. But things when you’re impacted like that, it becomes very discretionary, and then maybe even legal in costing you money. Well you’ve already abandoned your home, do you have money? I really don’t know. “

Ms. Terry said that the Army Corps has comment on previous documents expressing their serious concerns. “They are going to require them to be no net impacts to our flood capacity and we already know we have capacity issues at Sutter Bypass which is north. … There are 10 cofferdams that will go in. One at the Fremont Weir, three for the intakes, and the six barges. … These cofferdams have to stay in place during the construction. Five to six years those cofferdams are out in that water. What do you have? Constrained channels for flood flow for six years in ten different places.”

Ms. Terry said she told the steering committee that the conservation measures calling for habitat restoration were more flood projects than habitat projects because they are proposing to modify facilities that are part of the State Plan of Flood Control. The Paterno decision here was very clear. “The facility is still the state’s obligation because they gave the assurance. Every single one of those habitat measures that we talk about doing, whether it’s for biops or BDCP or anything else, if they are modifying that State Plan of Flood Control … if eventually there is failure, the state is liable,” she pointed out.

Ms. Terry said she told the steering committee that the conservation measures calling for habitat restoration were more flood projects than habitat projects because they are proposing to modify facilities that are part of the State Plan of Flood Control. The Paterno decision here was very clear. “The facility is still the state’s obligation because they gave the assurance. Every single one of those habitat measures that we talk about doing, whether it’s for biops or BDCP or anything else, if they are modifying that State Plan of Flood Control … if eventually there is failure, the state is liable,” she pointed out.

The reclamation districts where the new facilities will be built won’t be able to do any levee projects because they can’t compete with the construction project going on, so that’s a ten-year period with no levee improvements, maintenance or possibly flood fights, said Ms. Terry. “I’ve told the districts, if I were you, turn those back over to the state, at least during that period, maybe forever … they shouldn’t be liable if they’ve modified and changed those levees, but particularly during construction, they are going to be vulnerable because of that dewatering. They didn’t analyze the dewatering and the sinkhole and subsidence on the levees, and combined with the pile driving that will occur … “

They analyzed traffic volume and pavement conditions, but not what’s underneath the black pavement, and most of their road segments are levees, pointed out Ms. Terry. “The levees aren’t built for the weight of the construction vehicles that so they will degrade those and that’s not even analyzed so therefore it’s not mitigated, which is one of the reasons why I told the districts to turn these back over to the state, you should not have any liability because they don’t have a plan to keep these up,” she said, adding “I hope as they go forward they will work on those things.”

Ms. Terry said the fish will be impacted by noise and vibrations and the reduced water flows that are a combination of the diversion intakes and the diversion that happens in the Yolo Bypass, which reduces the flows in the rivers and the streams and channels below that.

“Is it your position that every potential damage must be fully mitigated or avoided?” asked Chair Phil Isenberg.

“CEQA is down to a less than significant impact,” Ms. Terry responded. “I guess the way I look at it as a Delta resident, my answer would be yes, and the reason I would say that is I think we’re all okay with sharing the responsibility for our statewide water supply and we’re already contributing to that, but in this case, this is the only HCP that I know where you are going into someone else’s backyard in order to use their properties for purposes of creating benefits in your own areas, and they have real impacts.”

“And with all the habitat restoration planned in the Delta, will we as local maintainers, have lands available to mitigate our levee improvements that with climate change need to be done?” Ms. Terry asked

“I am hoping the Delta Stewardship Council will really try to look at what some of these unique values are that were identified in statute, in terms of the agriculture resources, the community characteristics, because if you don’t have access to your parcels for those years … they really do become quite blighted, and yes you can say they are in discrete areas, but they are in what a lot of us would consider the heart of the Delta – a high tourism area and a lot of high end high value permanent crop areas,” said Ms. Terry. “These aren’t low value lands, so I hope the DSC will try to take some time to think about what are the values and what constitutes that really unique agricultural environment because it is unique.”

For more information:

- Click here for agenda and meeting materials.

- Click here for the staff report for this agenda item.

- Click here for Steve Centerwall’s power point.

- Click here for the webcast.