With the acknowledgement that the state’s water situation needs a comprehensive solution, one that extends beyond the reach of the Bay Delta Conservation Plan, discussion has turned to what things should be included in such a solution. One item that seems to make everyone’s list is storage in some form, be it surface storage or groundwater storage. Even some environmental groups have joined the chorus for more storage projects, recognizing a need for greater water storage in the face of climate change, growing populations, and other factors.

California has been studying large surface storage projects since the1990s, yet some studies have yet to be completed, let alone constructed. However, during this same time period, local agencies have constructed and built over 1.2 MAF of above ground storage and 4 MAF of underground storage. Councilmember Randy Fiorini has authored an issue paper that suggests that the state’s water storage needs could be met by building smaller reservoir projects, many of which are already on the drawing boards, but for whatever reason, aren’t moving forward.

Mr. Fiorini presented his issue paper at the Delta Stewardship Council’s November 22 meeting, bringing in a panel consisting of hydrologist Robert Shibatani, the Friant Water Authority’s Mario Santoyo, and Northern California Water Association’s Todd Manley to discuss water storage projects.

Photo by John Menard

Councilmember Randy Fiorini began by noting that he grew up in an area that is serviced the state’s largest locally owned water storage facility, Don Pedro Reservoir. “Don Pedro Reservoir has served our area very, very well,” he said. “There’s adequate water stored to meet most of the driest of year conditions; in most years it has adequately addressed flood control issues, and it also provides in-stream flows for the Tuolomne River.”

There are two recommendations in the Delta Plan that specifically address water storage: Recommendation WR 13 calls for the completion of the surface storage studies regarding Sites, Temperance Flat and the enlargement of Shasta Dam and their fate decided, and Recommendation WR 14 says that state agencies should conduct a survey of possible storage projects that could be implemented in the next 5 to 10 years.

“Generally speaking, 13 or 14 years ago, under CalFed, the Department of Water Resources was tasked with identifying potential storage projects in support of gaining additional flexibility for the water system, particularly the State Water Project,” began Mr. Fiorini. “They looked at primarily large projects that could effectively be used to reregulate or reoperate the system. Of the 53 potential projects that they looked at, they summarily dismissed a number of them simply because they were under 200,000 acre-feet in capacity.”

“Since that time, DWR and the Bureau have undertaken studies of initially five projects and now it’s down to three. One of those that was initially looked at was Los Vaqueros; Contra Costa Water Agency decided not to wait for the state or federal investigations but took it upon themselves, and in this period of time, they did the studies, they did the construction, they added a second phase, and now they are considering a third phase. This is a local agency in action. At the same time, the studies for Temperance Flat and Sites continue to roll along although not very smoothly and have yet to be completed for a number of good reasons.”

Mr. Fiorini said that his paper offers six recommendations:

1. Complete the studies of Temperance Flat, Sites, and the enlargement of Shasta Reservoir so we can evaluate whether or not these are good projects, he said. “It has been a financial issue … and there’s has been no champion for these projects because of the uncertainty in most cases.”

2. There is a need to identify who will be the beneficiaries of each project. “As a starting point for a conversation that if you were to do Temperance Flat or Sites, whoever it is that steps forward and says that they can use the water, give them 50% of it, and dedicate the other 50% for the public trust, for instream flows, for temperature control, and so on,” said Mr. Fiorini. “In my mind, it’s a way to address the coequal goals and to give the water agencies who step forward and say we want to pay for this some certainty.” (Note: Mr. Fiorini’s specific recommendation in the paper says: “The Governor and the state Legislature should support legislation that ensures state funding for 50% of total cost and operation of each of these projects for the defined public benefits portion supporting ecosystem health for the Delta.”)

“The last four recommendations deal with the idea there are a number of local smaller projects that are out there that could be beneficial to help meet the coequal goals and regional sustainability, and those measures that we spell out and recommend in the Delta Plan,” said Mr. Fiorini.

3. Revisit the August 2000 CalFed water storage study based on new information and modern objectives since at the time, CalFed was primarily looking for large projects. “Take another look at the 53 locations that were mentioned,” he said.

4. Conduct a statewide survey of local public water agencies to determine potential locations for new or enlarged water storage projects. “There are water agencies throughout the state that have local projects that could be done so expand the list and find out what’s out there,” said Mr. Fiorini. “Utilize the water commission, along with participation with ACWA and one or two NGOs, because there are aspects of storage that are beneficial to fish and fowl, so I think it’s important to have the NGOs a part of this study process or survey process.”

5. Develop funding strategies to assist locals with water storage projects. “Many times local agencies have not pursued these projects because they are cost-prohibitive for limited local value, but if there’s a cost-share component, either federal or state or both, it may make these projects more doable,” he said.

6. Improvements to water storage project permitting are necessary. “It can be very difficult, so a recommendation to help accelerate the acquisition of permits to move forward on these valuable projects is the sixth recommendation.”

“My hope is that with minimal adjustments to this document, it will be something the Council would like to approve and that we can begin disseminating it to generate more discussion regarding above ground and below ground storage,” he said. And with that, he turned to the first panelist.

Robert Shibatani, hydrologist

Robert Shibatani began by noting that he had recently testified at a House Subcommittee on Water and Power hearing on water storage where he discussed the benefits of high-elevation storage, how it is different than previous historic water supply projects, the emerging trends in new storage development, and the long term prospects are for using storage projects in the future.

Photo by Christine4nier

High-elevation storage projects are not new; we’ve been discussing them for a number of years, said Mr. Shibatani. “For the oversight hearing, we felt very strongly that with the emerging interests in new dams and reservoirs across the nation, it is time to elevate the new discussion on new storage as a primary top priority of U.S. domestic water policy.”

“High elevation storage projects involve new upstream impoundments that are above existing facilities,” he said, noting that these facilities would be above existing state, federal, and local agency impoundments defined as terminal or rim reservoirs. “There are a number of distinguishing factors that make these new facilities quite different than their historic counterparts,” he continued. “Number one, they are at a high-elevation which means they are at the source of the snow accumulation and the potential effects for climatic shiftings that we are now starting to observe in our high-elevation watersheds. Number two, they are at remote locations, which means many of the population displacement risks that might typically associated with new high-elevation storage projects are normally reduced relative to those facilities nearer higher population density centers.”

He noted that construction-related effects such as air quality, noise effects, public utility issues, community disruptions, traffic delays and land use conflicts are largely marginalized relative to those facilities that might be more closely situated near high-population density centers. “The final point is that the distal proximity of these high-elevation storage reservoirs, relative to their downstream outflow … there are interceding reservoirs that exist between these high-elevation storage facilities and the downstream point which means that in general, many of these high-elevation facilities are largely immune or at least somewhat unaffected by existing downstream water quality control objectives, like what we experience in the Bay Delta,” he said.

Capturing upstream precipitation in the source areas provides a strong benefit for downstream flood protection, and there are a number of ecosystem and environmental benefits that can accrue later on in the year, things like habitat protection flows, side channel backwater pool replenishment, fish attraction flows, and pulse flows for water quality which is very important in estuaries where salinity intrusion is an issue, as well as the dilution potential that has significant benefits for the many thousands of NPDS and waste discharge requirements that are currently in existence today, he said.

“New high-elevation storage can provide operational flexibility to those jurisdictions that happen to enjoy joint state and federal operations, and the new yield generated can also provide additional long-term supply sustainability and resiliency for local purveyors,” he said. “They can also help support and augment those water purveyors who happen to benefit from a robust and active water transfer market for the last 10, 15, 20 years.”

Photo by John Trapp

“From an endangered species perspective, high-elevation storage combined with coordinated operations within systems can also indirectly generate additional reservoir cold pool assets which is very important for downstream instream thermal management,” said Mr. Shibatani. “So the aggressive temperature-related actions associated with NOAA’s biological opinions, we can provide additional yield ability to enhance compliance with many of those temperature targets downstream.”

From a climate change perspective, new dams can provide an effective climate change adaptation because dams provide the attenuation capability of that flood peak for additional runoff that’s occurring earlier in the year as brought about by warming temperatures or a change in precipitation form, he said. “Such things as altered watershed hydrographs, interannual yield differentials experienced between water years, and even such things such as extreme event probabilities can each be accommodated in certain degrees by new high-elevation storage.”

Mr. Shibatani said that when he is asked if new reservoirs and facilities are even possible in today’s regulatory framework, he answers that with a question of his own. “For the watershed in question, the first question that I ask as a hydrologist is, does that watershed in any given water year experience either surplus flows or uncontrolled releases?” he said. “We all know in the western and mountain states is yes, because of the snow dominated hydrologic reality of those watersheds. So it is that uncaptured yield that I want to serve as a foundational basis to help rationalize and justify new storage development. … if the hydrologic answer to that question is yes, then our responsibility as resource managers, water experts and water practitioners means that we’re compelled to develop and support a regulatory framework that actually can meet that hydrologic truism.”

“There are a number of additional challenges that lay ahead; clearly many of them are regulatory-driven,” he said. “In my experience in developing storage across California, I’ve never seen a more pressing need for new storage; I am quite optimistic sitting here today in 2013, because I do see a lot of factors and stars lining up in favor of new storage that we have perhaps haven’t experienced in the past several decades. We have pressing needs for long term supply security and resiliency, instream habitat protection, downstream flood control, and downstream water quality control including protection against saline intrusion brought about things such as sea level rise. We have a need for clean energy; we have a strong need for upstream source area watershed protections because of the effects of climatic forcings.”

New high-elevation reservoirs can provide a very effective platform to help solve the yield differential in many of the western and mountain states, he said. “It boils down to the question of overall integration,” he said. “Several facets are associated or involved with things such as system operations, the need to use updated climate hydrology, the need for new regulatory adaptations, and all of these factors, in my view, have to be integrated; they can’t be dealt with in isolation. But if they are integrated, they can maximize our ability to implement effective and efficient long term water supply storage development projects.”

“It’s no secret in my mind that storage in and of itself is not the panacea … that is a truism, it is not the exclusive solution,” said Mr. Shibatani. “It has to be integrated with other prescriptions.”

Storage has to be the starting point, and there are a number of reasons for that, he said. Our infrastructure was developed 50 to 100 years ago and were developed based on a series of assumptions about water demand, population projects and regulatory framework at the time. “We all know that that has migrated over the last 50 to 100 years and climate change and its effects on baseline hydrology has only accelerated that gap, so we’re sitting here today and we have two options. Number one, regulatory transitions to move the gap or reduce the gap from this side or take the other gap reduction from the infrastructure side, because unless we do that, the gap is growing and our best efforts to try and meet some of the coequal and multiple public trust objectives that we’ve been struggling with for the past several decades, we won’t stand a chance of doing that.”

Mr. Shibatani said that he was working with legislators in DC on some specific concept initiatives that he hopes will move forward in 2014 that include closing the flood control and water supply gap by reestablishing the new net system yield in California because of new storage, integrate instream and unimpaired flow objectives under the projected enhancement brought about by new storage, a new climate-sensitized regulatory framework that identifies some of the significant risks associated with shifted climate and what it means to long standing regulatory approvals, and a strong and robust encroachment for private sector investors to jump into the fray in new storage development.

“I strongly believe that some of these projects should be focused on a smaller basis,” he said. “What’s the bottom line in the end if we have 25 small regional projects that we can develop in 7 years versus waiting 20-25 years to finally get the appropriate funding to develop major state and federal projects.”

Mario Santoyo, Friant Water Authority

“I am really encouraged with the whole fact that this Council is looking into storage and hopefully will be sending out a strong message in terms of its importance,” began Mario Santoyo, General Manager for the Friant Water Authority. “My discussion will be different than the prior speaker because I am not going to be talking hypothetical. I’m going to be talking actual, and I say that from the perspective that I’ve got 30 some years of actually operating large reservoirs under all conditions, whether they are in the 1977s during basically the driest years in CA, or in 1983s or in the wettest, or in the 1997 when we had the 100 year floods, I’ve operated reservoirs throughout that period. So I am going to tell you the reality.”

Photo by David Prasad

“I represent the Friant Division which was the cornerstone for the Central Valley Project and the first project that came into California under federal process in order to effectively stop subsidence in the Central Valley because it was because of groundwater overdrafting,” said Mr. Santoyo. “The primary mission for the Friant Division was to conduct conjunctive water use; in other words, bring in surface water in order for farmers to use in lieu of groundwater, but at the same, recharge the groundwater so that the water tables could be brought back to where they should be and stabilized.”

Achieving that requires surface water to meet the demands of municipalities and farmers, he said. “Our farmers grow the widest variety of crops in this nation, and in fact we represent those counties that are one, two, and three highest production ag counties in the nation,” he said. “So the area I represent is pretty important to the state of California – we represent about a $5 to 6 billion economy to the state.”

However, in recent years, the Friant division entered into the San Joaquin River restoration settlement agreement which has meant a about a 20% or 200,000 acre-foot reallocation of water to restore salmon runs in the San Joaquin River. “From a societal perspective, this is a good thing; however, you have to keep in mind, there’s a price to pay when you do that,” said Mr. Santoyo. “Because for the cities that depended on that water for delivery to meet their constituents and for the farmers that needed that water to maintain their ag production, that meant a change.”

“That caused us to go back and figure out how we can manage the existing water supply that we have so as to try to accomplish those goals,” he said. “The challenge we have, though, is that we have a really small reservoir. It’s only a half a million acre feet for an annual runoff of approximately 1.8 MAF. Those numbers don’t match, so what that means is that this reservoir has to turn over 3 to 4 times in order to try and manage that flow. It does not do it effectively. We lose on average about 450,000 acre-feet per year, almost one full reservoir is lost to flood releases.”

“Over the past 30 years, we have lost over 14 million acre-feet to flood releases, which does not do anybody any good, I don’t care what the arguments are,” said Mr. Santoyo. “I’ve lived it, I’ve operated it, and basically it boils down to when it comes down, it’s not coming down slowly, it roars, so you let it out as fast as you can and it goes to the Delta, and when it reaches the Delta, remember, in a wet year, it’s not just only our tributaries sending water into that Delta, all tributaries are sending water into that Delta, and that’s putting pressure on your levees.”

In order to reduce flood releases and convert them back into usable yields, an instream reservoir is needed, and Temperance Flat, built in the footprint of the existing reservoir, could accomplish that, he said. “I think from the perspective that you reevaluate a lot of small reservoirs, I think that’s wonderful, but I will tell you, because I’ve been involved in the full studies of this, there are a number of operational issues that make small reservoirs unfunctional. We don’t have time to go through all of that, but if they were viable, I guarantee you we would have been doing it 20, 30 years ago.”

In order to reduce flood releases and convert them back into usable yields, an instream reservoir is needed, and Temperance Flat, built in the footprint of the existing reservoir, could accomplish that, he said. “I think from the perspective that you reevaluate a lot of small reservoirs, I think that’s wonderful, but I will tell you, because I’ve been involved in the full studies of this, there are a number of operational issues that make small reservoirs unfunctional. We don’t have time to go through all of that, but if they were viable, I guarantee you we would have been doing it 20, 30 years ago.”

“It’s taken 10 plus years of hard studies to get to where we are at today,” he said, noting that he didn’t see high-elevation reservoirs working above his reservoir. “We happen to be one of those reservoirs that has Southern California Edison that uses that river in a series of hydroprojects over which we have no operational control; they operate it to maintain power generation to Southern California. Pacific Gas & Electric has an additional couple of reservoirs, same purpose, so the only thing we have is a little tiny reservoir at the end of the stream that somehow we have to manage water that roars down there, so you can build all the little reservoirs in the high elevations that you want, it does absolutely nothing for anybody. Not in our case.”

“If we don’t look hard at actually creating a serious instream reservoir, we’ve got serious problems we’re not going to be able to overcome,” said Mr. Santoyo. “We are back to pre-project days because we can no longer provide that recharged water into the ground, so we’re counting our days in terms of when we’ll be back to such a serious situation that Californians will have a real problem.”

Phil Isenberg asked Mr. Santoyo if he agreed with Mr. Fiorini’s suggestion that local interests pay half the cost of new storage. Mr. Santoyo agreed, saying provisions in Chapter 8 of the water bond negotiated with the 2009 Delta legislation package laid it out that way and he was supportive of that.

“Then why isn’t is possible to put that deal together right now and walk into the state now and say here’s our half share, you pony up the rest, because right now the discussions on the big projects are truly theoretical,” said Mr. Isenberg. “There’s a lingering suspicion that the financial local share is not there. That may be wrong, but in the absence of a cold, hard offer to match payments from responsible entities, how else do we deal with it?”

“That’s understandable, and I can’t speak for any other project other than the project that I represent and that’s Temperance Flat for the Friant Division,” responded Mr. Santoyo. “We’re waiting for the feasibility study which will be done sometime in December or January. That in itself will tell us the feasibility of Temperance Flat, it will tell us the yield, it will tell us the cost, it will tell us any operational considerations, and it basically is going to tell us what we’re going to be buying, and until we know what we’re going to be buying, it’s hard to get somebody to sign up to pay for the dam. We have people who are interested but they are not going to sign anything until they know what they are going to buy.” Possible local interests include tribal councils in the areas, cities currently not receiving surface water, west side contractors, and maybe even Southern California interests, Mr. Santoyo said.

“Integrated Operations needs to be the way we operate in the future,” he said. “To date, we’ve been focused on operating reservoirs to provide strictly regional benefits, and from my perspective, those days are gone. We now need to figure out how do we operate all reservoirs in some fashion that helps each other, depending on the set of circumstances that exist during any given year. We’ve been pursuing that discussion heavily because San Luis Reservoir, who is the only major downstream storage from the Delta is pretty important and itself experiences conditions that reduce the availability of water south of the Delta.”

Temperance Flat provides additional flexibility due to its unique location, pointed out Mr. Santoyo. “Temperance Flat is not only considered above the Delta, it’s the only reservoir that’s considered above and below the Delta and that’s a pretty important fact,” he said. “Not only can we provide water to help the Delta, but we can deliver water across or deliver it south,” noting that it is this flexibility that makes integrated operations with San Luis Reservoir possible. “What I’m saying is Temperance Flat or any other reservoir in this state needs to be looked at in terms of how do you integrate it with any other reservoir for a better state operation rather than just a regional operation.”

“What would be the benefit to the Delta if Temperance Flat were to be built?” asked Councilmember Pat Johnston.

“Temperance is considered above the Delta, and the reason it’s considered above the Delta is because it when it releases its water, it moves northerly to the Delta, so having Temperance, which is essence increasing the cup you have to store wet water,” responded Mr. Santoyo.

“Would there be more water in the river, particularly in the drier months?” asked Mr. Johnston.

“That’s a good question, because in our settlement, there are six different type years. The two lowest, or driest, years – there’s really no water that goes into the river that makes it to the Delta, it’s probably not until you get to the third type does it actually make it to the Delta,” said Mr. Santoyo. “So if we had the larger cup, we would have more water available to have more continuous flow during the dry years and have that connectivity.” …

“The big price paid to the Delta and to the environment was the one in the 50s that diverted the water,” said Mr. Johnston, “so if you now say, well how can we improve it both for the farmers who have to share some of their water and improve it for the Delta and Temperance Flat or those kinds of projects could do that. Does the cost of that improvement to the Delta fall on only on the public side, the state side of payment, or do those who have economically benefitted for 60 years and continue to benefit have a responsibility for paying half of that cost?”

Photo by Maven

“If you stop and take a look at the history of California, because the situation at Friant is not singular, if you take a look at Hetch Hetchy, which took water, diverted water out of the San Joaquin River and then sent it through a pipe system to San Francisco which it still does today – it does not dedicate any water into the San Joaquin River so it continues to send its water there,” said Mr. Santoyo. “Now is that right, is that wrong? Those are decisions, but there are a number of those same examples, it was a societal decision … “

“Let’s take that as an example,” said Mr. Johnston. “So as Mr. Shibatani suggested, maybe we would have high-elevation reservoirs in some places; I’m not sure it’s a system that could take it, but let’s say for the sake of argument, above Hetch Hetchy you could do a project and that project was for San Francisco because it could get more hydropower money and so they wanted to do it. Wouldn’t the state’s interests come into play there because in the early part of the 20th century, all that water was diverted away from the Delta and there’s been a harm to the Delta and that if they wanted to do something else that would either enhance their water supply or made them more money, wouldn’t it be reasonable for the state to require a payment to improve the Delta?”

“It’s bigger than the question you asked,” replied Mr. Fiorini. “I think that the tension that exists in the San Joaquin Valley is one of insufficient surface water supplies, whether it’s on the west side because of Delta conveyance, or on the east side because of reservoirs like Lake Success and Isabella that can’t operate at full capacity because of seismic issues, or Millerton that should have been a 2 MAF reservoir that’s only 500,000 AF. The fact is that it’s less costly for growers, urban areas, and communities in those service areas to tap the groundwater than it is to build new surface water storage facilities to supplement their shortfalls, and there’s a train on the tracks that is coming. The water board is looking at increasing regulations on groundwater that if it goes in a particular direction, will force locals to look more largely and harder at surface water storage projects that will facilitate groundwater recharge projects.”

“The reason for my questions are to use that to get at what I think are policy issues that we have to think about, particularly the financing,” said Mr. Johnston. “The increase of storage is a worthy goal that should be supported and we should pursue. What I want to do is not defer to some other time who the beneficiaries are and not ignore the history and not ignore the fact that people mindlessly mine the underground; it’s just a function of capitalism run rampant, you just take all the water and when you run out, you move away or die or something; I don’t know what happens but the state’s interests in law is to help restore the Delta and these projects have to do that. It’s not like it’s the last thing and maybe when we get to it, condition 5 or 6 might get met if everybody else gets all the water they want. … “

“Before a project like Friant gets built, it goes through a lot of process, and in those days, it was actually the state of California that wanted to do this project because they were looking at how to create and economy in that area,” said Mr. Santoyo. “The picture was bigger than a few farmers wanting water. It was the State of California that wanted actually to do it, but had to hand the baton off to the federal government to actually implement it. There were decisions made by the state water board who looked at the fact that if by diverting that water to create this economy, there was going to be a consequence, and that consequence was that there was going to be the drying of a river. And that time, California said that’s our goal; this is more important than that. Was it right, was it wrong, I can’t tell you, but that was the decision that California made then; today’s a different day so now we have to meet some new objectives, so I am telling you that this project, from let’s say the Council’s perspective, should be focused on what can a project like that do to improve the Delta conditions and reliability … “

“I think it’s part of the genius of this conceptual approach [Fiorini’s paper] – it doesn’t require us to answer the 160 year old historic questions,” said Mr. Isenberg. “The Temperance discussion is in many ways what has prevented any rational discussion of smaller projects for 15 to 20 years, not just Temperance but others, comparably situated. We’ve managed to mess it all up; we all know we have to reevaluate it, and everyone mucks around, trying to find a way out of it … Randy’s proposal is attractive to me; it offers a slightly different approach to get us in to actions that might cumulatively benefit society as a whole and the individuals who live in it, not just rehashing the old agreements … Storage is part of everybody’s solution for the future, properly done.”

Mr. Santoyo then offered some recommendations. Storage as a whole is important, whether it’s big, small, above or underground is an important message to send out, the water commission needs to complete the public benefits regulations, and the California Water Plan needs to strongly identify water storage as a strategy tool because legislators need to see it there to facilitate funding of storage.

“The other thing I would caution … I don’t want to go backwards, so in doing the assessment of smaller projects, if you’re going to go back and revisit the ones that were done for Temperance, there was 22 sites, that’s ok. But let’s make sure that going back and revisiting them doesn’t reset the clock all over again to move the big project forward, so however, you do that, let’s make sure we are not hindering the forward moving of big ones in going back and assessing little ones.”

Todd Manley, Northern California Water Association

Todd Manley began by saying that the concept of coordination is important, not only in terms of conjunctive management, but also in the context of other water management tools. “Efficient water management and reservoir reoperation and utilizing that to meet needs … I’m not an engineer, but I get to work with a lot of them and I get excited about some of the things they are talking about and with coordination and flexibility in the system, we could really do some interesting things.”

Mr. Manley said he thought Mr. Fiorini’s issue paper hit the right note. The history is important, he said, but decisions made in the past seemed logical at the time but with the information we have now, maybe weren’t the best decisions. “Locating dams on rivers seemed like a perfect opportunity here to provide flood control and water supply, but obviously the more we learned about fish passage, it wasn’t the easiest choice to do, but that being said, I think that we’re going in now with our eyes wide open and recognizing that no matter what project you do, there’s going to be tradeoffs,” he said.

Completing the studies is important as it allows for the beneficiaries of the project to be determined, both public and local entities, and is important for moving forward and seeing if there’s interest in the project, he said. “It’s also lets people know what benefits are going to be provided for sustainable water management, both within a region and within a statewide perspective, as well as what can it do for the Delta, which is the primary interest here.”

Getting the studies completed is also important as it could be informational to the bond, he said, noting there are current discussions about reducing the size of the bond. “Are you going to be undermining efforts if you put that dollar amount too small because you realize that with all the different storage options, that maybe you left something on the table because you didn’t invest enough,” said Mr. Manley.

“I think there needs to be a gut check on every one of these projects,” he said. “People are either going to invest in these projects or they’re not … the expectation that somehow it’s going to be fully funded by the state and federal government, I just don’t think is a viable option, given the economic situation that we’re in.”

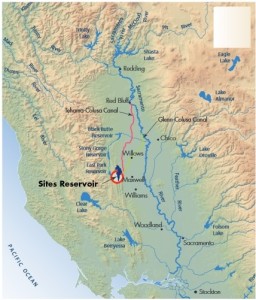

Sites Reservoir is located about 70 miles north of Sacramento. “A number of local entities created a joint powers authority for the project, and that really kicked off a lot of the work,” said Mr. Manley. “They are local government entities, water suppliers, as well as county governments. DWR sits on it in a non-voting capacity.”

Sites Reservoir is located about 70 miles north of Sacramento. “A number of local entities created a joint powers authority for the project, and that really kicked off a lot of the work,” said Mr. Manley. “They are local government entities, water suppliers, as well as county governments. DWR sits on it in a non-voting capacity.”

The JPA acquired funding to do the investigation and we’re starting to get preliminary data, he said. “Initial numbers now are that it’s about $3.4 billion for the project so it’s not cheap. We never went in thinking that was the case. There are early estimates on the public benefit which is key to get that mix of what the project’s going to provide, and at this point, the estimate is that it’s about 44%; it’s not quite 50% but this is a preliminary estimate on this. Out of that, the greatest public benefit is to the ecosystem which includes things like instream flows, and level 4 refuge water supply providing that terrestrial habitat water benefit as part of the mix as well. The second highest public benefit is water quality and I think that’s important as well because there’s a Delta aspect to that.”

DWR is scheduled to complete a public draft of the EIR/EIS by next spring, and the Bureau of Reclamation is working to complete a draft feasibility study by March or April of next year, he said. The JPA is working to complete new project performance modeling with a new BDCP 9000 cfs diversion and decision tree flows which is critical for identifying beneficiaries of the project and the public benefits of the project as well, and also the funding an updated higher level cost analysis to really hone in on the overall amount, and initiating local outreach to determine local interests concerns and to also look at further opportunities for local investment.

And in conclusion …

The Council passed a motion in support of Mr. Fiorini’s paper. “With the Council’s permission, I’m going to add a few changes based on some of the factual recommendations that have come to me since this draft was released, and hopefully a couple of weeks, release it publicly,” said Mr. Fiorini. “Hopefully it will do some good.”

For more information:

- Click here for Councilman Randy Fiorini’s issue paper on water storage.

- Click here for the staff report for this item.

- Click here for a FAQ sheet on Temperance Flat from DWR (dated2007).

- Click here for a FAQ sheet on Sites Reservoir from DWR (dated 2007).

- Click here for the meeting agenda, materials, and webcast link (when available).

Photo credits:

- Don Pedro Reservoir by flickr photographer John Menard

- Gerle Creek Reservoir by flickr photographer Christine4nier

- Ice House Reservoir by flickr photographer John Trapp

- Friant Dam by flickr photographer Dave Prasad