At the State of the Estuary conference held at the end of October, Professor Jay Lund from UC Davis Watershed Sciences and also PPIC fellow gave a presentation on his view of how adaptive management could be applied to move forward in the Delta. Jay Lund began by noting that he and the PPIC researchers had worked on a report on stressors, titled “Where the Wild Things Aren’t”, which was all about the Delta. His presentation followed that of Ellen Hanak’s, where as part of her presentation, she reviewed the five categories of stressors of discharges, direct fish management, flow regime changes, invasive species and physical habitat loss and alteration, which were defined and organized in the PPIC Report, Aquatic Ecosystem Stressors of the Delta.

At the State of the Estuary conference held at the end of October, Professor Jay Lund from UC Davis Watershed Sciences and also PPIC fellow gave a presentation on his view of how adaptive management could be applied to move forward in the Delta. Jay Lund began by noting that he and the PPIC researchers had worked on a report on stressors, titled “Where the Wild Things Aren’t”, which was all about the Delta. His presentation followed that of Ellen Hanak’s, where as part of her presentation, she reviewed the five categories of stressors of discharges, direct fish management, flow regime changes, invasive species and physical habitat loss and alteration, which were defined and organized in the PPIC Report, Aquatic Ecosystem Stressors of the Delta.

“So we are all multiple-y stressed and the Delta is no different,” he said. “Just to sort of remind you all of how stressed this place is, here’s a map what the Bay-Delta system looked like back in 1848, and what’s its like today. The Delta was part of that system and this is what it was like roughly before it was pulverized into what it is today.”

“So we are all multiple-y stressed and the Delta is no different,” he said. “Just to sort of remind you all of how stressed this place is, here’s a map what the Bay-Delta system looked like back in 1848, and what’s its like today. The Delta was part of that system and this is what it was like roughly before it was pulverized into what it is today.”

Diversions were a huge change in both the physical landscape and the hydrological landscape, he said. “We see even up into the 1920s, this ‘growing up’ in terms of upstream diversions and those diversions becoming quite important and affecting the flows in the Delta and the salinity in the western Delta,” said Mr. Lund. “During droughts, salinity spread even into the Central Delta, which at the time, the Delta exporters were very happy to have the export projects because that would regulate the winter flows so they could flush the salt out to sea during the drought periods in the summertime.” “I sometimes think that Delta management is really about hostage taking, and that’s the current hostage that’s dying.”

Diversions were a huge change in both the physical landscape and the hydrological landscape, he said. “We see even up into the 1920s, this ‘growing up’ in terms of upstream diversions and those diversions becoming quite important and affecting the flows in the Delta and the salinity in the western Delta,” said Mr. Lund. “During droughts, salinity spread even into the Central Delta, which at the time, the Delta exporters were very happy to have the export projects because that would regulate the winter flows so they could flush the salt out to sea during the drought periods in the summertime.” “I sometimes think that Delta management is really about hostage taking, and that’s the current hostage that’s dying.”

This is our sorry state, he said. “We have all these multiple stressors, we have declining native species, and on the science side, we have a pretty fragmented management establishment and still quite fragmented science establishment,” he said. “Certainly the new Delta Science Plan is an effort to move away from that direction.” “We have disorganized public science which has led to combat science, and I think we’ve seen examples of that even very recently with each side having its own scientists and they sort natter each other,” he said. “I think we as a public and the agencies that represent the public have let this happen by not getting our act together as state agencies and as public interests to insist that there be a strong public science program, because when that science program becomes fragmented, we have a lot more room for combat science. I think we’ve also seen at least anecdotally poor development and use of science to enlighten and provide insights and suggestions to the folks that have to make the policy decisions and the management decisions. There are all very smart people but we’re pretty all disorganized about it both at the science level and at the management level, and the management folks who are trying to make the best use of science, they aren’t very well organized either.”

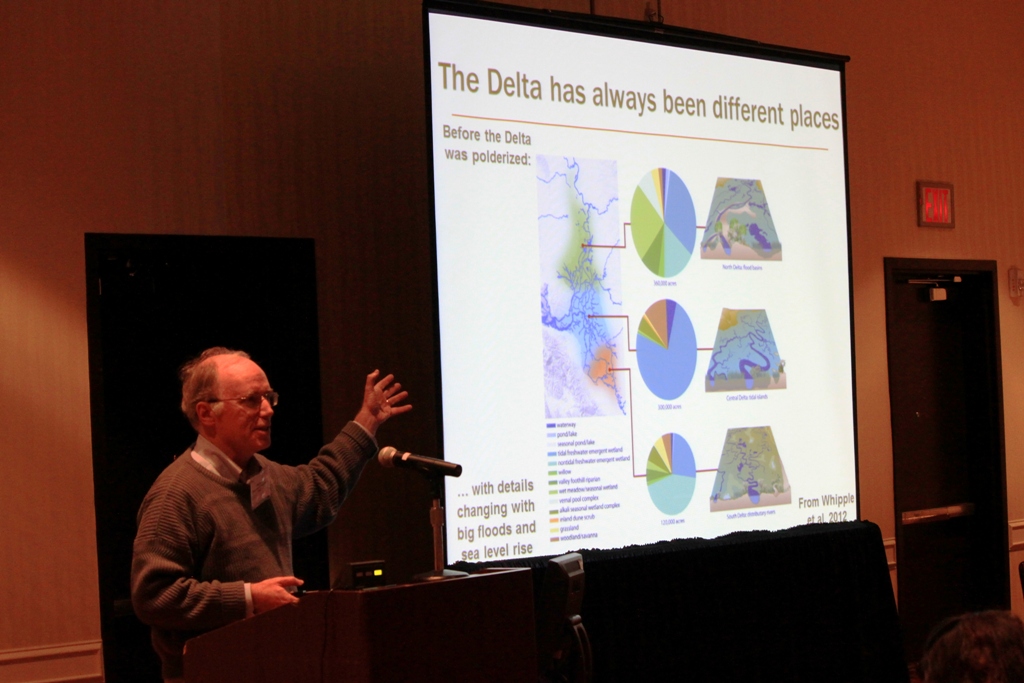

This is our sorry state, he said. “We have all these multiple stressors, we have declining native species, and on the science side, we have a pretty fragmented management establishment and still quite fragmented science establishment,” he said. “Certainly the new Delta Science Plan is an effort to move away from that direction.” “We have disorganized public science which has led to combat science, and I think we’ve seen examples of that even very recently with each side having its own scientists and they sort natter each other,” he said. “I think we as a public and the agencies that represent the public have let this happen by not getting our act together as state agencies and as public interests to insist that there be a strong public science program, because when that science program becomes fragmented, we have a lot more room for combat science. I think we’ve also seen at least anecdotally poor development and use of science to enlighten and provide insights and suggestions to the folks that have to make the policy decisions and the management decisions. There are all very smart people but we’re pretty all disorganized about it both at the science level and at the management level, and the management folks who are trying to make the best use of science, they aren’t very well organized either.”  Mr. Lund then turned to his vision for the path of future Delta diversity. “In the past the Delta was different places, and different parts of the Delta had different dominant geomorphological processes going on; this would have changed between years that had big floods and years that didn’t, and over the course of the last 6000 years or so as sea level rose throughout the system.”

Mr. Lund then turned to his vision for the path of future Delta diversity. “In the past the Delta was different places, and different parts of the Delta had different dominant geomorphological processes going on; this would have changed between years that had big floods and years that didn’t, and over the course of the last 6000 years or so as sea level rose throughout the system.”

There are a lot of continued drivers of change in the Delta, much as some of the stakeholders might want to deny or accentuate them; they are all happening, he said. “We still have some physical instability in the Delta – not everywhere but in many places in terms of land subsidence, sea level rise, floods, earthquakes and things like that,” he said. “We have continued ecosystem instability with new invasive species and continued habitat alterations and continued playing out with habitat alterations that might have occurred some time ago, plus prohibitive costs of maintaining all the islands and worsening water quality for agriculture and urban users – in particular, I think, for the urban users because when was the last time you saw drinking water standard get loosened.”

There are a lot of continued drivers of change in the Delta, much as some of the stakeholders might want to deny or accentuate them; they are all happening, he said. “We still have some physical instability in the Delta – not everywhere but in many places in terms of land subsidence, sea level rise, floods, earthquakes and things like that,” he said. “We have continued ecosystem instability with new invasive species and continued habitat alterations and continued playing out with habitat alterations that might have occurred some time ago, plus prohibitive costs of maintaining all the islands and worsening water quality for agriculture and urban users – in particular, I think, for the urban users because when was the last time you saw drinking water standard get loosened.”

“The Delta of tomorrow is going to be different no matter what we do, whether we have tunnels or we don’t, no matter what we do in the Delta,” said Mr. Lund. “In many of its places, it’s going to be quite different then today. There’s going to be some larger earthquake and flood risks that going to lead to larger open bodies of water; we’ve been seeing this over the decades, as islands by islands failed. Of the last three islands that failed, two of them were abandoned by the landowners. They were making their own benefit-cost analyses and they did what they did. We’re going to see losses of some of these islands. They’ll be major changes in water supply, water quality, Delta land use, lots of things will change.”

“The Delta of tomorrow is going to be different no matter what we do, whether we have tunnels or we don’t, no matter what we do in the Delta,” said Mr. Lund. “In many of its places, it’s going to be quite different then today. There’s going to be some larger earthquake and flood risks that going to lead to larger open bodies of water; we’ve been seeing this over the decades, as islands by islands failed. Of the last three islands that failed, two of them were abandoned by the landowners. They were making their own benefit-cost analyses and they did what they did. We’re going to see losses of some of these islands. They’ll be major changes in water supply, water quality, Delta land use, lots of things will change.”

“The new Delta is going to be more diverse; it’s essentially going to go back a little bit to what it was in the past only different, and we’ll have to reconcile this,” continued Mr. Lund. “We’ll have island failures, more saline and more open water. Maybe we’ll have a levee policy. That would be a smart thing for us to do. It’s going to be worse for the water users, pretty much in any case, but it’s likely to be better for the fish. They’ll be more aquatic habitat, even though it might be deep water.” “Water exports are going to change in the location or they are going to face extinction over time,” he said. “We’ll probably have less water exports than people have gotten used to in the past, and if we manage it well, maybe we’ll be a little better off for fish and maybe better for the economy – we’ll have to see.”

“The new Delta is going to be more diverse; it’s essentially going to go back a little bit to what it was in the past only different, and we’ll have to reconcile this,” continued Mr. Lund. “We’ll have island failures, more saline and more open water. Maybe we’ll have a levee policy. That would be a smart thing for us to do. It’s going to be worse for the water users, pretty much in any case, but it’s likely to be better for the fish. They’ll be more aquatic habitat, even though it might be deep water.” “Water exports are going to change in the location or they are going to face extinction over time,” he said. “We’ll probably have less water exports than people have gotten used to in the past, and if we manage it well, maybe we’ll be a little better off for fish and maybe better for the economy – we’ll have to see.”

“When we talk about restoration, we talk about what’s possible in the Delta,” said Mr. Lund. “Elevation is everything. … Elevation is destiny, for habitat. What kind of elevations do you have to have for tidal marsh? They have to be about the tidal range. The Central Delta is way beyond tidal range so we’re likely to have quite a bit of deep freshwater lake habitat. … there will be some riparian habitat, some floodplain habitat, most of this is driven by elevations we see out there, so not every part of the Delta is suitable for everything. I think that’s something that the policy folks and the management folks don’t quite understand yet.” “So how do we try to manage this system for desirable diversity?” continued Mr. Lund. “We’re basically entering kind of a brave new world that’s going to be unexplored where we’re going to have estimates and models, and they’ll all be wrong. We’ll be really happy we did those analyses; it will prepare us for this world a little better, but we’re all going to be wrong. And I think we have to be prepared for that, and the politicians have to understand that as well.”

“When we talk about restoration, we talk about what’s possible in the Delta,” said Mr. Lund. “Elevation is everything. … Elevation is destiny, for habitat. What kind of elevations do you have to have for tidal marsh? They have to be about the tidal range. The Central Delta is way beyond tidal range so we’re likely to have quite a bit of deep freshwater lake habitat. … there will be some riparian habitat, some floodplain habitat, most of this is driven by elevations we see out there, so not every part of the Delta is suitable for everything. I think that’s something that the policy folks and the management folks don’t quite understand yet.” “So how do we try to manage this system for desirable diversity?” continued Mr. Lund. “We’re basically entering kind of a brave new world that’s going to be unexplored where we’re going to have estimates and models, and they’ll all be wrong. We’ll be really happy we did those analyses; it will prepare us for this world a little better, but we’re all going to be wrong. And I think we have to be prepared for that, and the politicians have to understand that as well.”  In Where the Wild Things Aren’t, the study team looked at where the native species are now and the areas of the Delta that are most suitable for sustaining these populations into the future, and they narrowed it down to the North Delta Arc. The study team came up with a rough specialization that could be applied to other parts of the Delta for different ecosystem purposes. “The Central Delta, let’s just keep that as a prized bass fishery. It’s one of the top 10 bass fisheries in the country; there are non-natives and it’s probably not going to change,” he said. “ We’ll probably get some native species that we have up here in the northeast Delta, and we have more of an estuarine Delta Arc from Suisun up to the Yolo Bypass.” “How can we manage these specialized areas?” continued Mr. Lund. “So much of our science, so much of our public dialog is about ‘let’s treat the Delta as one place’. And it’s not. And we probably don’t’ want it to be all one place. We don’t’ want it to be one homogenous mass. We’re probably not going to get the most out of it if we treat it like a homogenous mass. It’s like treating you all like one kind of biologist. We’re not going to get as much science out of you all if we treat you all the same.”

In Where the Wild Things Aren’t, the study team looked at where the native species are now and the areas of the Delta that are most suitable for sustaining these populations into the future, and they narrowed it down to the North Delta Arc. The study team came up with a rough specialization that could be applied to other parts of the Delta for different ecosystem purposes. “The Central Delta, let’s just keep that as a prized bass fishery. It’s one of the top 10 bass fisheries in the country; there are non-natives and it’s probably not going to change,” he said. “ We’ll probably get some native species that we have up here in the northeast Delta, and we have more of an estuarine Delta Arc from Suisun up to the Yolo Bypass.” “How can we manage these specialized areas?” continued Mr. Lund. “So much of our science, so much of our public dialog is about ‘let’s treat the Delta as one place’. And it’s not. And we probably don’t’ want it to be all one place. We don’t’ want it to be one homogenous mass. We’re probably not going to get the most out of it if we treat it like a homogenous mass. It’s like treating you all like one kind of biologist. We’re not going to get as much science out of you all if we treat you all the same.”  “In trying to organize science and the management of the Delta, some of the arguments that we’ve made in our work on multiple stressors is to try and manage the science and the management, particularly the adaptive management, geographically,” he said. “Tailor the management of the science to the different regions and the different objectives of each region. That allows us to do better overall, and to be more responsive trying to make this work.”

“In trying to organize science and the management of the Delta, some of the arguments that we’ve made in our work on multiple stressors is to try and manage the science and the management, particularly the adaptive management, geographically,” he said. “Tailor the management of the science to the different regions and the different objectives of each region. That allows us to do better overall, and to be more responsive trying to make this work.”

“So here’s a rough organization chart,” said Mr. Lund. “Let’s have the Delta Stewardship Council, and friends. I’m assuming everyone’s going to be friends with the Delta Stewardship Council. Under that, we have to have a Delta-wide Science program much as we have now, and probably a Delta-wide adaptive management program because there are some very large issues that need to be addressed Delta-wide. Now there will be the issues of managing total exports and things like that that affect every region, and there will be scientific issues in terms of quality control, peer review, larger strategic syntheses, and things like that, that need to be addressed Delta-wide, so there probably should be some sort of quality quasi-external quasi-independent external reviews quality controls to help keep things honest. Under that, you would have a series of more specialized programs that would focus on making each of these regions successful for their own local goals … and similar parallels essentially, science programs, where you can do the adaptive management at a more reasonable scale.” “Imagine what you have to do to do an adaptive management experiment at a Delta-wide scale,” he continued. “How many stakeholders do you have to line up? How many regulations do you have to line up? You don’t have a prayer of getting that done within a century. So, we have sort of a prayer of getting it done within 50 years at the area scale, and maybe even better chance at the project scale and the site scale. So let’s concentrate most of our field experiments at the site scale, do more of our experiments numerically at the area scale and the Delta-wide scale, because we can afford to make very few changes in the field, if only because of the regulations.”

“So here’s a rough organization chart,” said Mr. Lund. “Let’s have the Delta Stewardship Council, and friends. I’m assuming everyone’s going to be friends with the Delta Stewardship Council. Under that, we have to have a Delta-wide Science program much as we have now, and probably a Delta-wide adaptive management program because there are some very large issues that need to be addressed Delta-wide. Now there will be the issues of managing total exports and things like that that affect every region, and there will be scientific issues in terms of quality control, peer review, larger strategic syntheses, and things like that, that need to be addressed Delta-wide, so there probably should be some sort of quality quasi-external quasi-independent external reviews quality controls to help keep things honest. Under that, you would have a series of more specialized programs that would focus on making each of these regions successful for their own local goals … and similar parallels essentially, science programs, where you can do the adaptive management at a more reasonable scale.” “Imagine what you have to do to do an adaptive management experiment at a Delta-wide scale,” he continued. “How many stakeholders do you have to line up? How many regulations do you have to line up? You don’t have a prayer of getting that done within a century. So, we have sort of a prayer of getting it done within 50 years at the area scale, and maybe even better chance at the project scale and the site scale. So let’s concentrate most of our field experiments at the site scale, do more of our experiments numerically at the area scale and the Delta-wide scale, because we can afford to make very few changes in the field, if only because of the regulations.”  “We talked about adaptive management going in a circle, and we make the circle roll forward. We’ve all been through processes where we’ve been sort of going in circles, but we need to make this one move forward.” “So principles for science and adaptive management. As scientists, we have to think about adaptive management sort of philosophically as a science, mostly being about science. It’s not. If adaptive management is mostly about science, than we won’t see any experiments getting done. It’s mostly about management. Each of these adaptive management experiments on a large scale is going to involve millions of dollars of gains and losses to different stakeholders. They cannot be expected to take this quietly. So we’re going to have to be pretty careful about it. It’s mostly about management and we’ll try to get the science to work along those lines. I don’t see a practical alternative to that. We’ll need to manage each part of the Delta for the local conditions and the local objectives. Again, the place is too diverse, and we have too diverse of a range of objectives to try and get everything out of every place.”

“We talked about adaptive management going in a circle, and we make the circle roll forward. We’ve all been through processes where we’ve been sort of going in circles, but we need to make this one move forward.” “So principles for science and adaptive management. As scientists, we have to think about adaptive management sort of philosophically as a science, mostly being about science. It’s not. If adaptive management is mostly about science, than we won’t see any experiments getting done. It’s mostly about management. Each of these adaptive management experiments on a large scale is going to involve millions of dollars of gains and losses to different stakeholders. They cannot be expected to take this quietly. So we’re going to have to be pretty careful about it. It’s mostly about management and we’ll try to get the science to work along those lines. I don’t see a practical alternative to that. We’ll need to manage each part of the Delta for the local conditions and the local objectives. Again, the place is too diverse, and we have too diverse of a range of objectives to try and get everything out of every place.”  “Having said that, we still should have one Delta science with local subprograms. We’re going to need some overarching coherence, overarching technical and scientific programs to go along with the local, more specialized programs. And a similar thing on the adaptive management side,” said Mr. Lund. “I think one of the most difficult aspects of this will be trying to get a regulatory framework that helps lead this system along. We have a regulatory system which was very important and very useful in the 1970s for saying no to bad things. We are now in a situation with the Delta where, if we just say no, and try and keep the status quo, it only gets worse, so we need to try and figure out what’s a better trajectory than the status quo trajectory, and how do we figure out a regulatory system that moves us in that direction. That’s going to be a very different legal challenge and a very different kind of philosophical and practical challenge for the regulatory agencies, but the regulations will slow down any adaptive management process to prevent us from moving in any direction unless we find a way of getting them on board, so I think that’s really quite important. Essentially, they’re going to lead. That’s not a typical role for them.”

“Having said that, we still should have one Delta science with local subprograms. We’re going to need some overarching coherence, overarching technical and scientific programs to go along with the local, more specialized programs. And a similar thing on the adaptive management side,” said Mr. Lund. “I think one of the most difficult aspects of this will be trying to get a regulatory framework that helps lead this system along. We have a regulatory system which was very important and very useful in the 1970s for saying no to bad things. We are now in a situation with the Delta where, if we just say no, and try and keep the status quo, it only gets worse, so we need to try and figure out what’s a better trajectory than the status quo trajectory, and how do we figure out a regulatory system that moves us in that direction. That’s going to be a very different legal challenge and a very different kind of philosophical and practical challenge for the regulatory agencies, but the regulations will slow down any adaptive management process to prevent us from moving in any direction unless we find a way of getting them on board, so I think that’s really quite important. Essentially, they’re going to lead. That’s not a typical role for them.”  “What’s adaptive management look like?” said Mr. Lund. “Again, it’s mostly about management, less about science. Although we should do as much science in the course of this as we can but the management is really at the forefront of it otherwise we just won’t get it to work. The field experiments will be mostly local; as I said before, it will be pretty rare at the larger scales. It’s sort of like building a bridge. When they built the Bay Bridge, how many of them did they build? How many experiments did we do for the Bay Bridge? We built it once because it costs a bazillion billion dollars. In building that bridge, did they only do one model run? They probably did thousands and they did a lot of technical studies to make sure that when you did that once, it was mostly likely to work. We’re still going to test that experiment over the years.” “Most of the larger scale experiments are going to be numerical models because we can afford to do very few field experiments. The Delta regulatory framework needs to help the adaptive management moving along, and we’re going to have to go out of our way, in terms of being organized, to break these very complex problems into smaller, solvable pieces within a larger framework. I like to use the example of aircraft. Everyone here is flown in an aircraft before. How do you build an aircraft? Is it all done experimentally? There are mathematical models for every component of that and for putting it all together. They do some experiments, they do a lot of experiments on components and they do a few experiments at the whole scale. I think we have to get used to organizing complex problems in a similar kind of a way and it will be similarly expensive.”

“What’s adaptive management look like?” said Mr. Lund. “Again, it’s mostly about management, less about science. Although we should do as much science in the course of this as we can but the management is really at the forefront of it otherwise we just won’t get it to work. The field experiments will be mostly local; as I said before, it will be pretty rare at the larger scales. It’s sort of like building a bridge. When they built the Bay Bridge, how many of them did they build? How many experiments did we do for the Bay Bridge? We built it once because it costs a bazillion billion dollars. In building that bridge, did they only do one model run? They probably did thousands and they did a lot of technical studies to make sure that when you did that once, it was mostly likely to work. We’re still going to test that experiment over the years.” “Most of the larger scale experiments are going to be numerical models because we can afford to do very few field experiments. The Delta regulatory framework needs to help the adaptive management moving along, and we’re going to have to go out of our way, in terms of being organized, to break these very complex problems into smaller, solvable pieces within a larger framework. I like to use the example of aircraft. Everyone here is flown in an aircraft before. How do you build an aircraft? Is it all done experimentally? There are mathematical models for every component of that and for putting it all together. They do some experiments, they do a lot of experiments on components and they do a few experiments at the whole scale. I think we have to get used to organizing complex problems in a similar kind of a way and it will be similarly expensive.”  “To me the most difficult problem is can the agencies science-dance together. There’s different ways we can make the science plan work. But if we don’t do that, then we’re sort of doing slam-dancing, which is our normal Delta science-dance.” “How can we get these people to science-dance together, to adaptively-management-dance together? Real people, real agencies need a reason to work together. They are not going to do it out of altruism. People talk about trust. Trust doesn’t work – trust is nice, maybe it’s a necessary condition, but if it’s a necessary condition, well let’s just give up, because we’re not going to get all these parties to trust each other simultaneously. It’s just not going to happen.”

“To me the most difficult problem is can the agencies science-dance together. There’s different ways we can make the science plan work. But if we don’t do that, then we’re sort of doing slam-dancing, which is our normal Delta science-dance.” “How can we get these people to science-dance together, to adaptively-management-dance together? Real people, real agencies need a reason to work together. They are not going to do it out of altruism. People talk about trust. Trust doesn’t work – trust is nice, maybe it’s a necessary condition, but if it’s a necessary condition, well let’s just give up, because we’re not going to get all these parties to trust each other simultaneously. It’s just not going to happen.”

“We’re going to have to give them some reasons to work together, both promising for greater effectiveness and better dollars, and some regulatory requirements that can only come from the Stewardship Council, State Board, and the courts. And I think in the end, we also have fear of failure. We have to realize that if we don’t figure out how to do the dance together, we’re going to end up in a much worse place.”

“We’re going to have to give them some reasons to work together, both promising for greater effectiveness and better dollars, and some regulatory requirements that can only come from the Stewardship Council, State Board, and the courts. And I think in the end, we also have fear of failure. We have to realize that if we don’t figure out how to do the dance together, we’re going to end up in a much worse place.”

And now for some of that scientific disagreement …

“I seldom disagree with you more,” said Bruce Herbold. “You say that the Delta science is badly fragmented and all that, and we certainly have problems, compared to what? Because we have nine agencies working together, quarterly meetings of directors of those nine agencies, and we have decades of data that have been carefully made sure that they are comparable through time.” “And it’s been so effective at providing enlightened synthesis for policy,” responded Jay Lund. “I think the X2 standard is a remarkable combination of science and policy,” countered Mr. Herbold. “That’s one out of 500 issues we need to work on,” replied Mr. Lund. “I’d just like to know, compared to what,” said Mr. Herbold. “What would you look for – a better, less fragmented science because scientists are fragmented and that’s the way we work. We argue with each other and it leads to fragmentation. Where do they do it better? Give us some examples.” “I think we’ve done a terrible job of synthesis,” said Mr. Lund. “We’ve done a really terrible job of up until the last few years in particular in getting the scientific opinion together and organizing it in a way that is understandable to provide insights and motivation to policymakers. I think that’s pretty widespread. That’s the main area. If you look at computer modeling, right now we have an outbreak, an epidemic, of 2 and 3D models being developed for the hydrodynamics, all funded by different agencies, not talking to each other, by different contractors … we’re going in completely the wrong direction here.”

For more information:

- Click here for the PPIC report, “Where the Wild Things Aren’t: Making the Delta a Better Place for Native Species”

- Click here for the Notebook’s summary of this report.

- Click here to view Jay Lund’s power point.

- Click here for Jay Lund and Peter Moyle’s essay, Adaptive Management and Science for the Delta Ecosystem, from the October issue of the San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science Journal