On March 20, 2013, the Assembly Select Committee on Regional Approaches to Addressing the State’s Water Crisis held an informational hearing titled “The Science of Storing Water.” The hearing featured DWR’s Kamyar Guivetchi giving an overview of water storage in California, presentations on the operations of three groundwater banking programs, and a panel discussion on the future of water storage. This is the first of three-part coverage from the hearing.

Committee Chair Rudy Salas began by stating that the focus of the hearing is on the science of storing water and will address such issues as the state’s current storage situation, the potential capacity, and the resources and approaches needed to move forward with addressing water stability throughout the entire state. “Whenever we talk about water reliability, we must also address the Delta because the issues in the Delta remain a key driver as California continues to develop a sustainable water policy. If we can improve the Delta, we can improve reliability for the entire system,” he said. “The goal of this hearing is to have an open and informative discussion that will help the legislature and members of the public to understand the science of storing water, how to optimize our current resources, highlight current innovative case studies, and ultimately to consider our future options – how we are going to improve and stabilize our reliability throughout the state.”

Committee Chair Rudy Salas began by stating that the focus of the hearing is on the science of storing water and will address such issues as the state’s current storage situation, the potential capacity, and the resources and approaches needed to move forward with addressing water stability throughout the entire state. “Whenever we talk about water reliability, we must also address the Delta because the issues in the Delta remain a key driver as California continues to develop a sustainable water policy. If we can improve the Delta, we can improve reliability for the entire system,” he said. “The goal of this hearing is to have an open and informative discussion that will help the legislature and members of the public to understand the science of storing water, how to optimize our current resources, highlight current innovative case studies, and ultimately to consider our future options – how we are going to improve and stabilize our reliability throughout the state.”

“I believe water availability, efficiency, and accessibility is really the biggest economic driving factor facing our state into the future,” said then-Assemblyman Ben Hueso. “We have the difficult challenge of providing a stable water supply for both cities and farms, especially those farms that provide half of the nation’s supply of fruits and vegetables while at the same time, we want to make sure we protect our beautiful and unique environment, and that poses some unique challenges,” noting that climate change is becoming a bigger issue every year.

“I believe we need to take another look at some policies that our state is engaging in – we need to stop dumping perfectly drinkable water into the ocean as a policy because we need to find a way to augment our reservoirs or find a way to put that into groundwater storage,” said Mr. Hueso. “There are a lot of things to talk about in groundwater storage, in reservoir augmentation, and in getting water to the neediest areas.”

“I believe we need to take another look at some policies that our state is engaging in – we need to stop dumping perfectly drinkable water into the ocean as a policy because we need to find a way to augment our reservoirs or find a way to put that into groundwater storage,” said Mr. Hueso. “There are a lot of things to talk about in groundwater storage, in reservoir augmentation, and in getting water to the neediest areas.”

“One of the reasons why California is so productive is because we’ve made those investments,” he said. “To continue to keep pace with that demand, we’re going to have to continue to make those investments and for that we have to earn the public support and trust, but also encourage their participation to make sure that they are part of our solution of making California the jewel of our nation.”

“I live in a part of the state of CA that has the rich benefits of the history of hydrology,” said Assemblyman Jim Patterson. “It seems to me that by modernizing hydrology we can build on the success of past generations that have left us a wonderful hydrological system but also to modernize and build upon it. … I think the challenge for us is to figure out ways to improve and modernize our hydrological systems because it has demonstrated to be a very good scientific approach and effective approach to the water needs of CA. I also hope as we develop together these discussions and we learn together, that we will be thinking not in terms of our regions and our backyards, but that we will be thinking of California as a whole. And so north and south and east and west, we need to be together at the table, figuring out the very best way to modernize our hydrology and move California forward.”

KAMYAR GUIVETCHI, DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES

Kamyar Guivetchi, manager for DWR’s Statewide Integrated Water Management program, then gave an overview on the state’s water storage. He began by saying that California is a large and diverse state, composed of ten hydrologic regions, some of them the size of other states in the nation. “We have to keep that in mind as we move forward, so this idea that we should take regional approaches to benefit the people of California and at the same time take a statewide approach is apropos,” he said.

Kamyar Guivetchi, manager for DWR’s Statewide Integrated Water Management program, then gave an overview on the state’s water storage. He began by saying that California is a large and diverse state, composed of ten hydrologic regions, some of them the size of other states in the nation. “We have to keep that in mind as we move forward, so this idea that we should take regional approaches to benefit the people of California and at the same time take a statewide approach is apropos,” he said.

Mr. Guivetchi then presented a series of maps to illustrate that California’s precipitation varies from 200 inches per year in the north to less than five inches per year in the south as well as varying from year to year and that while most of the precipitation falls in the north, most of the demand lies in the central and southern part of the state.

“It’s that mismatch in space and time that really drove over the last 150 years, the development of a very extensive hydrologic system and facilities,” he said.

“It’s that mismatch in space and time that really drove over the last 150 years, the development of a very extensive hydrologic system and facilities,” he said.

About three-quarters of the runoff that is used in the state is locally controlled and locally developed, Mr. Guivetchi said. These include projects such as local surface and groundwater projects, and the water from the Colorado River used in the southern part of the state.

“Now the state and federal projects, while they don’t manage a large volume of water, their conveyance system is what is really value-added to the state,” he said.

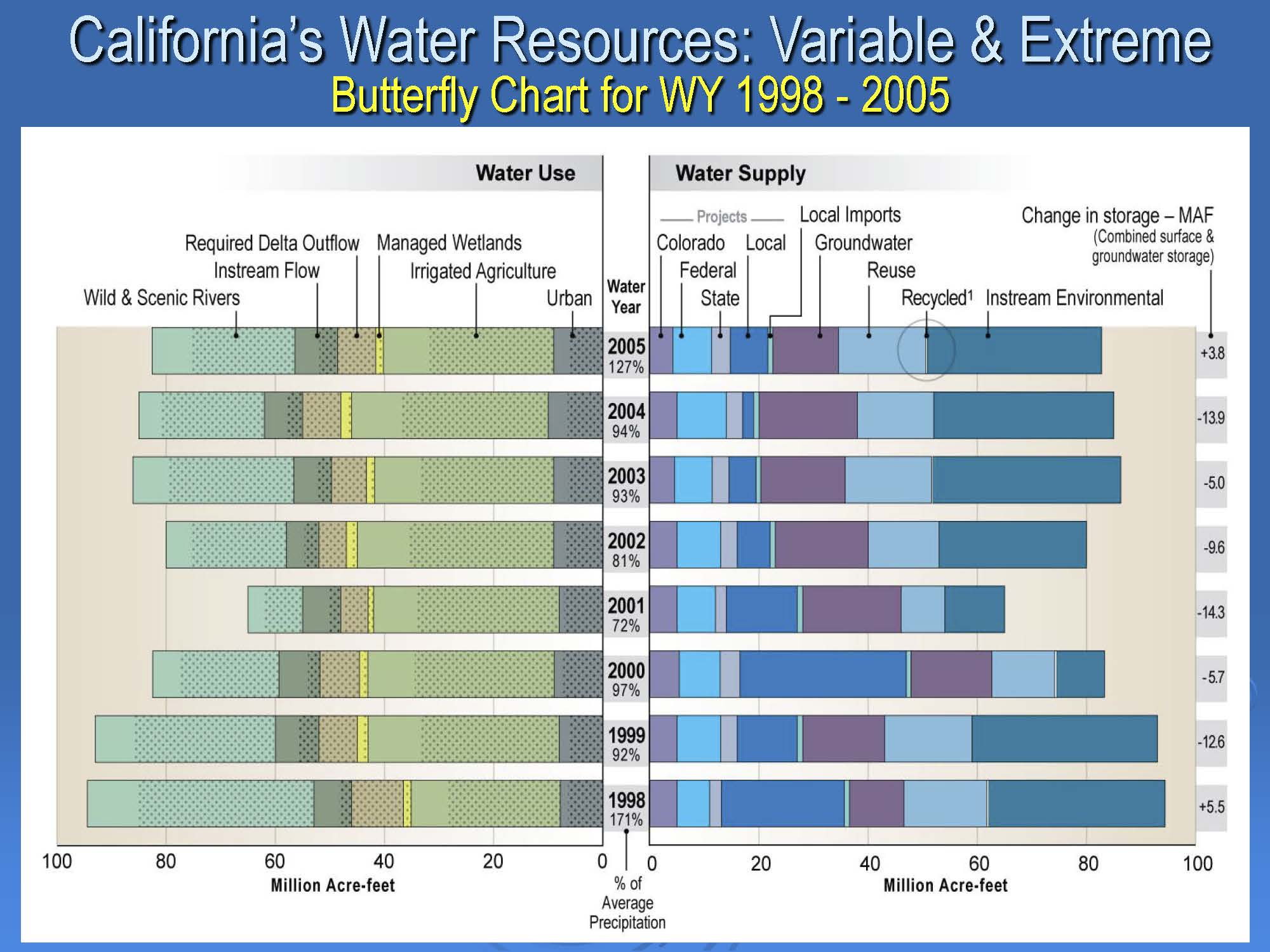

He then presented what he called the ‘butterfly chart’ from the California Water Plan.

He then presented what he called the ‘butterfly chart’ from the California Water Plan.

“The left wing of the butterfly chart shows the various types of water uses from 1998 on the bottom to 2005 on the top,” Mr. Guivetchi explained. “The right wing on the butterfly chart are the various types of water supply that was used to meet those uses in those years, and you’ll see that many of them again are the local surface water projects, groundwater, and then a small recycled water … we had to draw a circle around it because it’s so small to see at that scale.”

He noted that the right edge of the right wing represents the change in surface and groundwater storage during each of those years. “That is an important part of how water is managed in California,” he said.

He explained that California has four types of reservoirs: the snowpack, surface storage reservoirs, groundwater basins, and the water that’s retained in the soil in the landscape, and out of all of these, the snowpack is the state’s largest reservoir today. However, he warned that may change in the future. “If we look at all the physical reservoirs in the Sacramento Valley, on average they capture about 13.5 MAF per year. In the San Joaquin Valley, those reservoirs are about 11 MAF per year, and our snowpack is on average 15 MAF per year,” Mr. Guivetchi said. “A 5 degree Fahrenheit increase in our air temperature is estimated to reduce our snowpack storage by 4 to 5 MAF per year, so that would have a dramatic effect on how we would manage and move water in California. Climate change is only going to make it more challenging – the higher air temperature is likely going to mean higher evapotranspiration for agriculture and urban landscapes and the higher water temperatures are going to challenge our aquatic ecosystems.” He noted that the Scripps Institute has estimated that by the end of the century, the snowpack could be only about 20 to 40% of what it is now. “That would be really challenging,” he said.

He explained that California has four types of reservoirs: the snowpack, surface storage reservoirs, groundwater basins, and the water that’s retained in the soil in the landscape, and out of all of these, the snowpack is the state’s largest reservoir today. However, he warned that may change in the future. “If we look at all the physical reservoirs in the Sacramento Valley, on average they capture about 13.5 MAF per year. In the San Joaquin Valley, those reservoirs are about 11 MAF per year, and our snowpack is on average 15 MAF per year,” Mr. Guivetchi said. “A 5 degree Fahrenheit increase in our air temperature is estimated to reduce our snowpack storage by 4 to 5 MAF per year, so that would have a dramatic effect on how we would manage and move water in California. Climate change is only going to make it more challenging – the higher air temperature is likely going to mean higher evapotranspiration for agriculture and urban landscapes and the higher water temperatures are going to challenge our aquatic ecosystems.” He noted that the Scripps Institute has estimated that by the end of the century, the snowpack could be only about 20 to 40% of what it is now. “That would be really challenging,” he said.

He then presented a hydrograph showing the American River’s runoff for the last 100 years, and he noted that in 1956, about the middle of the hydrograph, is when Folsom Dam was completed. He pointed out that when the engineers designed Folsom Dam, they saw the hydrograph to the left of that. “What we have observed or experienced since then is a much flashier hydrology in the American River and this is not unique to the American River,” Mr. Guivetchi said. “If you saw the Sacramento and other major river systems, you would see a similar pattern. And what that means is that when the engineers designed that facility, they did not anticipate the hydrology that we’re experiencing now, so we cannot operate these facilities the way they were originally designed. That leads to this whole area called system reoperation, and so for instance, Folsom Dam is now in the process of being reoperated to make it more synchronized with the hydrology that we’re experiencing.”

He then presented a hydrograph showing the American River’s runoff for the last 100 years, and he noted that in 1956, about the middle of the hydrograph, is when Folsom Dam was completed. He pointed out that when the engineers designed Folsom Dam, they saw the hydrograph to the left of that. “What we have observed or experienced since then is a much flashier hydrology in the American River and this is not unique to the American River,” Mr. Guivetchi said. “If you saw the Sacramento and other major river systems, you would see a similar pattern. And what that means is that when the engineers designed that facility, they did not anticipate the hydrology that we’re experiencing now, so we cannot operate these facilities the way they were originally designed. That leads to this whole area called system reoperation, and so for instance, Folsom Dam is now in the process of being reoperated to make it more synchronized with the hydrology that we’re experiencing.”

“Sea level has risen seven inches in the last 100 years and it’s estimated that by the end of this century, it might be between 1 ½ to 4 ½ feet higher,” he said. “That’s going to put tremendous pressure on our Delta levees, on our estuaries and our coastal watersheds which are going to experience certainly higher water levels but also higher salinity intrusion into our groundwater basins along the coast.”

Groundwater basins are very important to California water management, he said. “We have about 515 basins and sub-basins; 57 of 58 counties have groundwater basins and they cover about 40% of the California landmass. One of the things to remember is that we shouldn’t pave them over – impervious surfaces on top of our groundwater basins are not going to help us.”

Groundwater basins are very important to California water management, he said. “We have about 515 basins and sub-basins; 57 of 58 counties have groundwater basins and they cover about 40% of the California landmass. One of the things to remember is that we shouldn’t pave them over – impervious surfaces on top of our groundwater basins are not going to help us.”

Groundwater management is locally controlled in California either through water code authority or county ordinances and/or court adjudications. “We now currently have 118 groundwater management plans that have been developed; they cover about 42% of the groundwater basin area which is less than half, so we can do better in California to develop groundwater management plans to make sure that we manage our groundwater better,” he said.

“Groundwater is hugely important – what these bar charts show is that for the ten hydrologic regions, the taller bar is how much water they used and the smaller bar is how much of the water came from groundwater,” he explained. “Now you’ll see in most regions, groundwater is a significant but not major water source; however if you look at the Central Coast and South Lahontan, most of their water supply is from groundwater, so in some regions of California, groundwater is tremendously important.”

“Groundwater is hugely important – what these bar charts show is that for the ten hydrologic regions, the taller bar is how much water they used and the smaller bar is how much of the water came from groundwater,” he explained. “Now you’ll see in most regions, groundwater is a significant but not major water source; however if you look at the Central Coast and South Lahontan, most of their water supply is from groundwater, so in some regions of California, groundwater is tremendously important.”

Groundwater overdraft, a long term reduction in groundwater supply, is estimated to be between 1 and 2 MAF per year, he said; however, groundwater overdraft is recoverable with active and good groundwater management.

We need to better monitoring of our groundwater basins, he said. “In 2009, part of the water legislation basically directed the Department of Water Resources to work with local groundwater entities to set up a statewide groundwater elevation monitoring and reporting program. We call it CASGEM for short, California Statewide Groundwater Elevation Monitoring.”

Mr. Guivetchi then updated the status of the surface storage investigations, an effort that was launched through the CalFed program. He explained that the storage projects have broad objectives and are designed in a way to provide new supply but at the same time, help improve environmental conditions and are based on the beneficiary pays principles.

Mr. Guivetchi then updated the status of the surface storage investigations, an effort that was launched through the CalFed program. He explained that the storage projects have broad objectives and are designed in a way to provide new supply but at the same time, help improve environmental conditions and are based on the beneficiary pays principles.

The five storage projects being considered are raising Shasta Dam, Sites Reservoir, Los Vaqueros expansion, in-Delta storage, and Temperance Flat. He noted that DWR did a lot of work on in-Delta storage and decided that the project didn’t pencil out, so it is not moving forward.

Contra Costa Water District recently expanded their reservoir by 60,000 AF to a total of 160,000 AF, and are continuing studies to raise it to a total capacity of 275,000 acre-feet. “Los Vaqueros Reservoir is primarily supplies the Bay Area, Contra Costa County, and it is in a position to provide south of Delta storage, but conveyance would have to be built that does not exist,” Mr. Guivetchi said.

If you combine the four projects in the surface storage investigation, “with existing Delta conveyance, we would get close to 800,000 acre-feet yield – that’s not just storage capacity but yield, new water, and we see that with new Delta storage, that amount stays about the same. In the dry periods, the yield is about 550,000 acre-feet and slightly less with new Delta storage and the reason new Delta storage reduces the yield is because some of the benefits of the storage without conveyance is handled through the new conveyance as far as water quality benefits to the Delta.”

If you combine the four projects in the surface storage investigation, “with existing Delta conveyance, we would get close to 800,000 acre-feet yield – that’s not just storage capacity but yield, new water, and we see that with new Delta storage, that amount stays about the same. In the dry periods, the yield is about 550,000 acre-feet and slightly less with new Delta storage and the reason new Delta storage reduces the yield is because some of the benefits of the storage without conveyance is handled through the new conveyance as far as water quality benefits to the Delta.”

Mr. Guivetchi then displayed a chart giving the schedule for completion of the surface storage investigations. “In the next year and a half to two years, the feasibility report and the environmental studies for these projects will be complete and then we will be looking for beneficiaries and people who would invest in the project,” he said.

Conjunctive water management is very important, said Mr. Guivetchi. “Groundwater and surface water together can provide a lot more flexibility, system resilience and yield, and what you need is sources of surface water, recharge methods, ways to extract and recover and reuse the water, and more importantly, we need to have the institutional framework that really incentivizes people who have surface water facilities to work closer with those who have the ability to store and extract groundwater.”

Conjunctive water management is very important, said Mr. Guivetchi. “Groundwater and surface water together can provide a lot more flexibility, system resilience and yield, and what you need is sources of surface water, recharge methods, ways to extract and recover and reuse the water, and more importantly, we need to have the institutional framework that really incentivizes people who have surface water facilities to work closer with those who have the ability to store and extract groundwater.”

DWR has been directed by the legislature to work on a system reoperation study, which is starting phase three of a four phase process. In the next year and a half, DWR should have some study materials out, however, he mentioned that DWR will be sharing the outcome incrementally. He also said that later this spring, they would have information on a pilot study done on the Merced River. “Again, the idea here is operating surface storage in conjunction with groundwater storage to maximize yield and flexibility and operations,” he said.

The California Roundtable for Water and Food Supply recently examined the state’s water storage resources, Mr. Guivetchi said. “What we tried to do in this roundtable is to really expand the concept of storage from just a surface storage project or a groundwater basin to thinking of our landscape as a way to retain and slow down the movement of water in the water cycle. We think there is a lot of opportunity to think of ways to use the natural landscape from the upstream meadows to our floodplains and doing flood management in conjunction with water supply and water quality management to realize more water retention.”

The California Roundtable for Water and Food Supply recently examined the state’s water storage resources, Mr. Guivetchi said. “What we tried to do in this roundtable is to really expand the concept of storage from just a surface storage project or a groundwater basin to thinking of our landscape as a way to retain and slow down the movement of water in the water cycle. We think there is a lot of opportunity to think of ways to use the natural landscape from the upstream meadows to our floodplains and doing flood management in conjunction with water supply and water quality management to realize more water retention.”

The Roundtable released a report, From Storage to Retention: Expanding California’s Options for Meeting its Storage Needs, that offers recommendations in four areas, he said: taking an integrated storage approach from upstream meadows through groundwater storage, improving information and data, improving institutional coordination, and improving communication and alignment amongst both our local agencies and the state agencies that have responsibility over water and certainly financing.

Integrated water management is what is really going to make this work, Mr. Guivetchi said. “There are 48 regional water management groups that are now recognized by the state of California; they cover 87% of the land area and 99% of our population, and their primary purpose is to come together and develop integrated plans that have multiple benefits and can really improve regional self sufficiency.”

Integrated water management is what is really going to make this work, Mr. Guivetchi said. “There are 48 regional water management groups that are now recognized by the state of California; they cover 87% of the land area and 99% of our population, and their primary purpose is to come together and develop integrated plans that have multiple benefits and can really improve regional self sufficiency.”

“Integrated flood management is a big part of this because we have to find ways to reduce flood risk while at the same time recharging our groundwater basins and improving our floodplain ecosystems,” he continued. “Our land use planning and management and our water management have historically been done by separate entities, and we have to use Integrated Regional Water Management and other ways to make sure that we plan on the land in ways that helps us in water management and vice versa.”

He noted that the California Water Plan now includes 30 resource management strategies. “These are tools in the toolbox that are available to regional and statewide planners to mix and match based on their regional and local conditions to meet their future water needs, and a number of these cover ways to improve storage and retention of water in California.”

He noted that the California Water Plan now includes 30 resource management strategies. “These are tools in the toolbox that are available to regional and statewide planners to mix and match based on their regional and local conditions to meet their future water needs, and a number of these cover ways to improve storage and retention of water in California.”

The whole idea of storage to retention is not to think of storage opportunities as just a physical facility, he said. “We can actually use the landscape, including our groundwater basins, to do that, and really what I think the reason these opportunities haven’t been realized is lack of communication, lack of coordination, and a very decentralized way of managing our water. Some person may have storage space in their groundwater basin, but if they don’t come up with a surface supply, they don’t have an opportunity for conjunctive water management. When people start getting together, they see those opportunities to work together and have mutual benefits and so I think the institutional framework is really what has kept us from realizing these opportunities.”

Coming up in part 2: A look at the technology and operations of groundwater banking programs currently in operation around the state.

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

- For Kamyar Guivetchi’s full power point presentation, click here.

- To watch this hearing on the California Channel, click here.

- For the report, From Storage to Retention: Expanding California’s Options for Meeting Its Storage Needs, from the California Roundtable for Water and Food Supply, click here.

- Visit the Assembly Select Committee on Regional Approaches to Addressing the State’s Water Crisis website by clicking here.

- To view all materials for this hearing, click here.