A second public meeting on the BDCP documents was held in Sacramento on April 4th to discuss the newly released chapters of the draft plan, which included the much-anticipated Effects Analysis as well as implementation and governance of the plan.

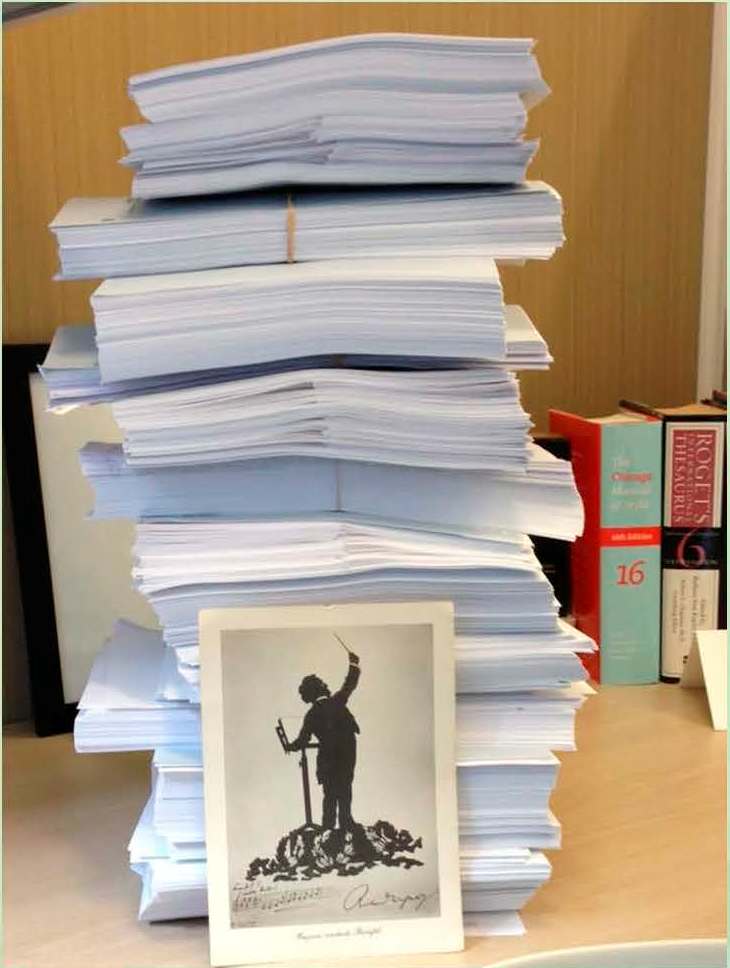

A draft EIR will be posted the first week of May, and will be about 20,000 pages. It won’t be an official public review draft, and so they won’t be able to respond to every comment at this time. However, the goal is to release the BDCP and the EIR/EIS for official public review this summer.

SECTION 3.6 ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT

The meeting picked up where the previous had left off, with Chris Earle, senior ecologist for ICF International, presenting on the BDCP’s adaptive management, monitoring and research program.

The meeting picked up where the previous had left off, with Chris Earle, senior ecologist for ICF International, presenting on the BDCP’s adaptive management, monitoring and research program.

“Adaptive management, monitoring and research are all intended to address uncertainty. They address primarily uncertainty regarding how the natural system functions, uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of the implementation of the conservation measures, and various other types of uncertainties that are related to the operation of the Plan and that are intended to be addressed to ensure that the plan is more effective over time,” said Dr. Earle, noting that adaptive management and monitoring are a requirement of HCPs and NCCPs.

Monitoring would be performed by the Implementation Office and addresses three things: compliance, effectiveness and trend monitoring. “Compliance monitoring is simply intended to find out if the plan is doing what it said it would do in the way that it said it would do it. Effectiveness monitoring is intended to determine if the conservation strategy is actually having its intended effects. And trend monitoring is used to evaluate the performance of the plan over time, which is important to evaluate many of the biological objectives which are tied to certain goals that have to be achieved by certain time points in the course of the plan,” said Dr. Earle.

Research actions would be funded by the implementation office but performed by researchers most likely working under grants to addresses key uncertainties in the conservation strategy: “If you look at Chapter 3, Section 3.4, in the description of each of the conservation measures, it talks about some of the ways in which, due to existing limitations in science, we are uncertain about the effects of those conservation measures. In many cases, specific research actions are proposed in order to reduce those uncertainties early in the plan term, although it’s anticipated that uncertainty will remain throughout the plan and that the research programs will be a continuing activity.”

Adaptive management is performed by the adaptive management team comprised of representatives of the permitting agencies, as well as the permit applicants and the Bureau of Reclamation and would work through a consensus process, Earle explained. “The adaptive management team guides the process of adaptive management, and its actions can be triggered by a variety of different things. For instance, unexpected effects of the plan that may be observed out there, declines in covered species populations that are inconsistent with the plans goals and objectives, or simply insufficient progress on the goals and objectives.”

“Adaptive management can be initiated in response to new information that alters scientific understanding. Scientific investigation in the Delta is an extremely fertile effort; scarcely a week goes by that we don’t find something new and interesting about the functioning of Delta ecosystems and so this process is expected to continue indefinitely; it will guide our understanding of Delta Science and our understanding of the most appropriate techniques of managing Delta ecosystems for the indefinite future.”

“Adaptive management may also be triggered by certain changed circumstances,” said Dr. Earle, noting that the topic of changed circumstances is fairly involved and is covered in more detail in Chapter 6.

“In response to these adaptive management triggers, a variety of things could occur. The most likely possibility is that there might be a change in conservation measures. For instance, a conservation measure might be emphasized if it turns out to be particularly cost-effective or simply to have a greater effect than was originally anticipated. The strategy for implementing the conservation measure may change if new scientific research, understanding, monitoring results, and so forth indicate that a different approach to the conservation measure is more likely to achieve the stated biological goals.”

“Adaptive management can also change the biological objectives. The biological goals represent aspects of Delta science that we pretty well understand at this point, and that we can say with confidence. For instance, an increase in an abundance of a particular covered fish species is going to be a desirable target. We can’t necessarily how quickly that should happen or exactly which parameters should be measured in order to understand it over time. Those are specified in the biological objectives. And consequently the precise formulation of the biological objectives is likely to change over time as our understanding of the science changes.”

“Adaptive management can also simply include a continued monitoring or research if new information indicates that there’s a technical problem out there or there is an aspect of Delta science that we may not have even been previously aware of that requires study, then adaptive management can consists of requiring a research program.”

“The BDCP has limited authority. There are many legal authorities that are operational in the Delta. And there may be changes which appear desirable but are not in the power of BDCP to cause to occur. Adaptive management can include making appropriate recommendations,” he said.

——————————

Comment from Suzanne Womack, farmer and school teacher who has lived at Clifton Court for 50 years: “Adaptive management, I’d like to address that. … (citing problems requiring re-rocking of levee, squirrel issues) … We’ve been working with Department of the Interior, we’ve had so many problems over the years dealing with those two groups that I’m really afraid that BDCP is just going to be a bigger mess to deal with … we can’t get anything right now when we have a state and federal department, how are we going to get any changes when there’s big problems? We’ve had 40 years of problems … “

Question from internet: Why can’t we leave the Delta the way that it is?

Jerry Meral answers:” If nothing was done and this program didn’t exist today, the Delta would not remain as it currently is. We know that without a continued huge investment of money, the Delta would be a very different place. And we’re investing that money presumably in a way the people in the Delta want. (laughter) For those who are laughing, the state has spent $300 million in improving Delta levees over the last 10 years, and that was at the request of Delta agencies. I assume they still want it. If they don’t, they should let us know.”

Question from the internet: What are the plan measures included in BDCP so as not to repeat the history of the San Joaquin River? We all know about the problems with the San Joaquin River. It took a long time to cause the problems, it’s taking a long time to recreate something like the fishery that was there at one time. Will this happen to the Sacramento River?

Jerry Meral answers: “Part of what the adaptive management program is all about is to make sure in fact that there’s is no detriment to the Sacramento River and its fisheries but an enhancement. “

Carl Wilcox, Department of Fish and Wildlife, adds: “From a species perspective, there are a lot of conflicts that exist with water reliability and the ability to maintain species moving forward, and that’s what BDCP is about. It is trying to develop a way to provide for the conservation of species but also provide for a level of water supply reliability. And the way we export water now is not the best way to do it, relative to managing the ecosystem.”

Statement by Representative from Congressman Garamendi’s office (couldn’t get the name): “I’m with Congressman John Garamendi who represents California’s 3rd Congressional District, and I think that we all feel that we need to think about water in a comprehensive way in California. The controversial BDCP is an outdated and destructive plumbing system. It does not create any new water nor does it provide the water and ecological protection that the golden state must have. California and the federal government must set aside this big expensive destructive plumbing plan and immediately move forward with a comprehensive approach that would include six things, those six things being conservation, recycling, the creation of a new storage system or systems, fixing the Delta with the right sized conveyance, levee improvements, and habitat restoration, all of this being done with a science driven process and protecting existing water rights. And that combination of six factors would constitute a comprehensive water plan for the state, of which the BDCP is not. It does not create one new gallon of water, it does not solve the long term needs of the state, with the minimum expected construction and operating costs that’s estimated over 50 years to be $24.5 billion, at the minimum. It is an extraordinarily expensive plumbing system coated in habitat restoration. The plan simply takes water from region and delivers it to the next, so my question to you would be if one of the coequal goals is water supply reliability, why does your plan does not really focus on the components of supply and yet on conveyance? Perhaps we should redefine that coequal goal to be water conveyance reliability … ? I would also like Congressman Garamendi’s plan to be considered as an alternative. I have copies of it here … We really need to look at a comprehensive approach here, people.”

Meral responds: “I will say that we will include several of the components that the Congressman wants us to include in the EIR/EIS when it comes out. And we’ll also look carefully at the other elements of the plan that he is suggesting.”

Michael Borodosky, Save the Delta alliance: “We talk about endangered species, listed species, the salmon are threatened. What this adaptive management plan does is puts our state and federal regulators at risk because what it is is it’s a plan for regulatory capture. So how is that the case? You have an adaptive management team that has to operate by consensus to make a decision. The water contractors have a seat on that team. So any recommendation that it would make that would involve reducing water exports, water contractor raises his hand and says I object. The decision is then held inoperative, it has to go up to two more committees … [noting that the action can continued to be appealed] it’s elevated to the US Secretary of Interior and the Governor of the California on the state side. Finally some decision will be made. This will take years. … You say it’s not a delegation of authority, but what it is is a procedural regulation that specifies a process for them to take that gives them the enormous ability to block anything that would reduce water exports.”

Jerry Meral answers: “There’s one element in your comments – that were generally accurate – that is missing. If an adaptive management action is needed to avoid jeopardy, which is after all one of the purposes we’re trying to accomplish here, and it was blocked the way you said, then the agencies do have another out. They can always say that the plan is threatening jeopardy for any of the species that are listed and the plan is suspended. And so if that long time period resulted in that kind of biological threat, they have the ability to do that, and that’s not subject to any veto by anyone else at all except themselves. So I think it would be foolish for anyone, the water contractors, DWR, BOR, to attempt to block and adaptive management action that was needed to preserve these species because the ultimate threat which we cannot evade or overcome is the jeopardy determination, so I don’t think you’re analysis reflects what would really happen.”

Bob Wright, Friends of the River, Environmental Water Caucus: “I’d like to address a couple of things very specifically to the NMFS and the USFWS. The country depends on your agencies to protect our endangered species. … And what the two federal fish and wildlife agencies are being asked to do here in the BDCP plan process is basically contract away your powers to protect the declining and endangered fish species in the Delta and the rivers in Northern California under section 7 of the ESA with a section 10 permit. And then down the road, if you require any mitigation measures, that would be not on the tab of the exporters; that would be on the price tag for the federal taxpayers. The federal agencies, you really need to stop, look, listen, and step back on this. This is a massive scheme to tie your hands and take away your section 7 powers and limit you to a very difficult process with all kinds of burdens on the federal agencies to revoke or suspend a permit down the road.”

Federal wildlife agency official: “This is certainly been a large topic of discussion. We are very closely guarded our section 7 responsibilities and abilities under this plan and they certainly will not be affected whatsoever. This is a non federal agency; the Bureau of Reclamation will also be involved with water operations which is a federal agency, and that is who we’ll most likely be doing our section 7 consultations with. And nothing about this plan will change that.”

Comment by Osha Meserve, North Delta Agencies: “I was looking at the adaptive management for CM1 in chapter 3, and I guess I was a little bit concerned … on pages 3.4.-23, the key uncertainties that look like they are research areas for the operation of CM and adaptive management – it seems like a very truncated list of all of the uncertainties that would be involved with CM1, so I just wanted to make the comment that, for instance, there are a lot of uncertainties about the interrelationship of habitat creation and the ability to divert water with water quality issues and other things in CM1. … I also wanted to comment that it doesn’t appear to me that CM1 is really very susceptible to adaptive management because it gets built right at the front end and it’s already there and then the only thing we’re looking at is how to operate it. It’s not like some of the other conservation measures where you really do have the opportunity to change what it is. From a local perspective, we’re very concerned about all the negative impacts locally and region-wide that cannot be fixed once it gets put into place, even if it is operated differently.”

Dr. Chris Earle agreed that it is a truncated list. “There are a variety of other topics that are currently being discussed with the fish and wildlife agencies. For instance, there is a fairly lengthy list that deals with bypass flows, and the design of the fish screens on the new north Delta intakes, and there’s also the question of what kind of studies will have to be done before the decision tree is put into implementation. These are areas of active discussion right now, and that section will look quite a bit different in the next draft.”

CHAPTER 4: COVERED ACTIVITIES

Dr. David Zippin then gave the presentation on Chapter 4. “Chapter 4 describes in a fairly summary form the activities we are intending to cover by the permits. It’s a required element of all HCPs and NCCPs. The chapter describes the activities that will be covered by the state and federal incidental take permits and includes the construction of the new facilities in some detail,” Zippin said, noting that there is a lot more detail in Chapter 3, as well as the project description of alternative 4 in the EIR/EIS.

Dr. David Zippin then gave the presentation on Chapter 4. “Chapter 4 describes in a fairly summary form the activities we are intending to cover by the permits. It’s a required element of all HCPs and NCCPs. The chapter describes the activities that will be covered by the state and federal incidental take permits and includes the construction of the new facilities in some detail,” Zippin said, noting that there is a lot more detail in Chapter 3, as well as the project description of alternative 4 in the EIR/EIS.

The chapter discusses the relative federal and non-federal roles under BDCP; Section 4.2 is a description of the activities associated with the conservation strategy, which is really 99% of what is covered in the plan, Dr. Zippin said.

The federal actions are associated with the operations of the CVP in the Delta only; operations outside the Delta of either the CVP or SWP are not covered, Zippin said. “Only those activities that are inside the plan area are subject to the section 7 consultation process, and so the Bureau of Reclamation will be obtaining their take authorization through that section 7 biological opinion, but we anticipate it would be completely consistent with BDCP.”

——————————–

Comment from Connie Wrightman: “I am the executive director for the Innertribal Council of California, a tribal association with membership throughout the state of CA. When you mention federal actions and joint action activity, our tribal leadership has been concerned about the lack of tribal consultation under executive order of the President of the USA for federal agencies, and under the executive order of the Governor for state agencies to involve tribes in various activities that impact their resources in federal lands, their tribal government lands. It is not clear how tribal governments have been consulted in this process, nor how federal agents representing federal agencies have engaged the tribes in the process. … we would like to have more clarification as to how the tribal governments could be involved in consultation on this process as provided under federal and state policy.”

David Nawi, Department of the Interior responds: “ The DOI takes its obligations to the tribes as sovereign entities very seriously. We will look very closely at the extent to which any federal actions impact tribes and their resources, and I’ll be sure to follow up to be sure that appropriate consultation takes place to the extent that it fits into the process we follow.”

Federico Barajas, Bureau of Reclamation: “I am interested in getting your contact information. Reclamation is specifically working with the other two fish agencies here in this project; we have actually provided some outreach in the past during the previous draft documents, and we’re in the process of reaching out as these documents are being drafted. We’re going to be reaching out to the tribes as part of our regular consultation process, so we do have something in process. … We have done that in the past, and if for some reason you haven’t seen that to date, I want to make sure you are included in our distribution list so that you get that kind of information in the future.”

Question from Burt Wilson: “Adaptive management has always appeared to me as the BDCP’s version of the get out of jail free card. When you have chapters filled with the most repeated word … is assuming, is assuming that this or that happens … it’s like playing dice with the Delta. … Is there money for this, does this increase the price?”

Meral answers:” You’re right, there is an adaptive management team described in Chapter 7, they do have the power to call on independent scientists to help them with an analysis of what needs to be done to at least respond to their recommendations. We do have funding for changed circumstances in Chapter 8 which we’ll get to at our next meeting. You’ve put your finger on all the key things that they have to do and in fact they are authorized by the plan to do it.”

Mr. Wilson asks who is going to vet this?

Mr. Meral answers: “The fish agencies, biological agencies are really the ones that have the lead on this, the own Department of Fish and Wildlife and the two federal agencies that are here today. They have to take the lead in looking at the monitoring and seeing if an adaptive management change is needed. Anyone can propose one; we have a variety of ways to hear them, but in most cases, it will be the biological agencies that will be the lead on trying to implement or at least try to initiate adaptive management.”

Comment by Jan McCleery, Save the CD Alliance, who is concerned about the impacts of construction on boating in the Delta, noting that one of the construction sites is Mildred Island, a popular place for boating. She is also concerned that there is a large muck site slated to be about 1 mile away from Discovery Bay. She is concerned about impact of smells on Discovery Bay residents, as well as the chemicals in the much leaching into groundwater or waterways. What happens in an earthquake?

Jerry Meral answers: “All the issues you raise are good ones. The question of the chemical nature of whatever is excavated during the tunnel needs to be looked at very closely. … I don’t think anyone up here thinks that the absolute final location of each and every one of these facilities has been determined. This isn’t even an official plan, it’s still just an admin draft, and we’re willing to work with the interest groups that you represent and others to try and make this a more acceptable project.”

Tim Newhart, farmer on Sutter Island: “These hearings are really nothing but time to check off the box that we’ve had public hearings. This process is going to continue until there’s an uproar about what this is doing and where this is placed. … How does 9000 cfs going out and around the Delta help maintain the health of the Delta? It does not. This proposal is in the wrong place … you know there are alternatives out there. Dr. Pyke’s Western Delta Intakes Concept is one of them. Far better and far viable. Meral you have the ear of the governor and you should be telling him about alternatives to the BDCP.”

Jerry Meral answers: “We will be analyzing alternatives in the EIR – 15 of them all at the same level of analysis so you will be able to see if we are analyzing any that you like.”

CHAPTER 5 EFFECTS ANALYSIS

The presentations then continued, with Jennifer Pierre, ICF International, discussing the much-anticipated Effects Analysis. Chapter 5 is the largest component of the plan; it is over 600 pages long and has 10 topical appendices associated with it, began Ms. Pierre of ICF International. “The purpose of the effects analysis is to describe the biological effects that the plan will have on each of the covered species,” she said. “For each one of the covered species, we present our biological conclusions about what the overall effect will be on each species from all of the covered activities.” She noted that this is information that the fish and wildlife agencies will use to issue their permits.

The presentations then continued, with Jennifer Pierre, ICF International, discussing the much-anticipated Effects Analysis. Chapter 5 is the largest component of the plan; it is over 600 pages long and has 10 topical appendices associated with it, began Ms. Pierre of ICF International. “The purpose of the effects analysis is to describe the biological effects that the plan will have on each of the covered species,” she said. “For each one of the covered species, we present our biological conclusions about what the overall effect will be on each species from all of the covered activities.” She noted that this is information that the fish and wildlife agencies will use to issue their permits.

(Note: The Effects Analysis evaluates the biological outcomes of the Plan’s activities and actions. It is not a substitute for the EIR/EIS, which is an extensive analysis environmental impacts, as well as looking at alternatives to project. The draft EIR/EIS will be available the first week of May.)

“A really important point to remember is that the Delta has been highly altered over the last 100 years or more and that there’s no way to return it to its natural state. Levees, climate change and other factors have made that impossible, so that isn’t actually what the BDCP is trying to accomplish. Instead we’re trying to reverse the decline of these species and to conserve them,” she said.

“Moving into the future, we think there’s likelihood that species will continue to decline if we don’t do anything … we can’t keep doing what we’re doing from a biological perspective for our covered species. And climate change is likely to make things worse,” she said. “This does provide the only mechanism on the table right now for widespread and large regional restoration of ecosystems in the Delta.”

The analysis compares the predicted effect of the BDCP to existing conditions, which includes the existing NMFS and FWS biological opinions, she said. Climate change means we are looking at a future condition in which the ecosystem is likely to degrade from climate change, so when we look at our ability to conserve each species, which is our goal, we’re also looking at that against a changing baseline; it’s not static, she explained. “so while our contribution to recovery might be large and our beneficial effect for a species might be large, when we take into consideration all the detriment that climate change might cause, we have what might appear to be a smaller benefit than we should to the species overall and a lot of that is driven by climate change.”

The analysis compares the predicted effect of the BDCP to existing conditions, which includes the existing NMFS and FWS biological opinions, she said. Climate change means we are looking at a future condition in which the ecosystem is likely to degrade from climate change, so when we look at our ability to conserve each species, which is our goal, we’re also looking at that against a changing baseline; it’s not static, she explained. “so while our contribution to recovery might be large and our beneficial effect for a species might be large, when we take into consideration all the detriment that climate change might cause, we have what might appear to be a smaller benefit than we should to the species overall and a lot of that is driven by climate change.”

Section 5.1 is the introduction and the summary of conclusions; Section 5.2 briefly summarizes the methods used, with additional details included in the 10 technical appendices. “We used over 35 physical, biological and conceptual models just for the fish analyses,” she said.

The environmental baseline or existing biological condition (EBC) reflects the conditions at the time of BDCP approval; it also includes the anticipated ecological effects of implementing most of the actions in the smelt and salmonid biological opinions, she explained.

“We have two time periods we look at. First time period we look at is 2025; this is the time period that we assume that CM1, the new conveyance facility, would first be online and operating; we look at the effects of restoration and all the other pieces of the conservation strategy along with CM1 operations,” she said. “And then we look again at the end of permit term, which is 2060. Each of those conditions have unique components related to sea level rise and climate change and the amount of restoration and different aspects of the plan that would be going on simultaneously and so it’s a pretty complex analysis. We call 2025 period the ‘early long-term’ and the 2060 period the ‘late long term,’” she said.

Over 68 models were used: “We have biological models, physical models, and conceptual models. We use habitat suitability indices and population and life history models. We basically used every single method that has ever existed out there unless it’s been so inapplicable that we just couldn’t use it.” She also noted that in many instances, three to five different methods were applied to analyze that particular effect.

Section 5.3 describes ecosystem and landscape effects. “This is our step back to look and see what is happening at the ecosystem level, not at the species level, but how are we changing the ecosystem. And one of the first improvements we see is in south Delta flows. … By transferring from a single point of diversion in the Delta to two different points, including the new conveyance facility, we’re able to substantially improve the reverse flows, especially in the wetter years.”

Right now, as the Sacramento River enters the Delta, it is being pulled toward the south Delta instead of moving west towards San Francisco Bay, she explained, and with the diversion point in the north Delta, “the south Delta flows are improved, because that pull is reduced so now you are seeing less movement from north to south and more movement east to west. “

“The other most obvious change is the restoration of over 100,000 acres; 55,000 of this is actually tidal wetlands and inundated areas, but another good portion of it is other types of natural communities that would be restored within the within the Delta,” she said. “As part of that restoration and as part of the dual conveyance proposal, we are able to provide a lot more climate change adaptation, and this is by creating upland transitions. … The idea is as climate change creates added pressure on these species, the BDCP through restoration and through the dual conveyance and other stressor reduction measures can provide some buffer against some of those stressors.”

There might be some improvements related to dissolved oxygen, predation, and invasive aquatic vegetation, said Ms Pierre. They also analyzed sediment loading in this version of the draft and found mixed results overall from a biological perspective.

Relative to salinity, ”we did not find any of the salinity changes were biologically meaningful. Again we are not looking at drinking water quality, that’s not an issue we evaluate in the BDCP, but for salinity effects on species, we did not see that as an issue.”

Ms. Pierre said that the BDCP is not proposing to change the operations of Shasta, Folsom, and Trinity reservoirs, and there are no changes in the Upper San Joaquin River or the reservoirs associated with it either. “We are making higher releases out of Oroville in the spring, so you have higher spring flows on the Feather, but we’re not changing our flood or storage capacity at the end of the season in September, so there are lower flows in the Feather River in the summer. So that’s fully analyzed,” she said.

Ms. Pierre then turned to the fish. “We have 11 covered fish: splittail, green and white sturgeon,  all of the Chinook salmon runs on both the San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers, central valley steelhead, pacific and river lamprey, Delta smelt, and longfin smelt.”

all of the Chinook salmon runs on both the San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers, central valley steelhead, pacific and river lamprey, Delta smelt, and longfin smelt.”

To determine the effect on a species, the first thing that we do is identify a list of attributes … so for every species, we look at each one of the attributes and determine how important is that attribute to a species. “Is it very important for Delta smelt to have turbidity or not very important. We answer that question. … We decide how important this particular attribute for each life stage,” she said, noting that they work, with the fish and wildlife agencies to make those determinations.

“Then we multiply by the effect that the BDCP will have on that attribute, so that provides a conclusion of beneficial or adverse effect and what the magnitude of that effect is.” Certainty is also considered: “How certain are we of the importance of that attribute, how certain are we of the BDCP’s effect on that attribute, and therefore what our overall certainty is on this conclusion.”

The Delta smelt spend their entire life in the plan area; they generally spawn upstream and move into downstream for rearing in summer and fall, so they have a high exposure to the changes the BDCP makes, said Ms. Pierre. There is a small potential for reduction in turbidity and an increased exposure to contaminants that might come from restoration activities as well as some minor entrainment and impingement impacts at the north Delta intakes, although Ms. Pierre noted the location of the intakes is in an area that’s outside of their range. However, there’s a substantial benefit through increased tidal habitat and food. “We have some uncertainty around that because of clams and the effectiveness of restoration, but overall with the volume of restoration that’s being proposed, we feel that there’s definitely evidence for substantial increased food availability. We are also reducing entrainment, moving to dual conveyance and moving the north Delta intakes outside of the species range, which all but eliminates south Delta entrainment in the wetter years and doesn’t make it any worse in the drier years, and so overall when you are looking across water year types you have some pretty good reductions in Delta smelt entrainment. … “So for all of those reasons and the fact that most of the adverse effects on Delta smelt that we are seeing are small, we found that Delta smelt would have a net benefit from BDCP.”

The Delta smelt spend their entire life in the plan area; they generally spawn upstream and move into downstream for rearing in summer and fall, so they have a high exposure to the changes the BDCP makes, said Ms. Pierre. There is a small potential for reduction in turbidity and an increased exposure to contaminants that might come from restoration activities as well as some minor entrainment and impingement impacts at the north Delta intakes, although Ms. Pierre noted the location of the intakes is in an area that’s outside of their range. However, there’s a substantial benefit through increased tidal habitat and food. “We have some uncertainty around that because of clams and the effectiveness of restoration, but overall with the volume of restoration that’s being proposed, we feel that there’s definitely evidence for substantial increased food availability. We are also reducing entrainment, moving to dual conveyance and moving the north Delta intakes outside of the species range, which all but eliminates south Delta entrainment in the wetter years and doesn’t make it any worse in the drier years, and so overall when you are looking across water year types you have some pretty good reductions in Delta smelt entrainment. … “So for all of those reasons and the fact that most of the adverse effects on Delta smelt that we are seeing are small, we found that Delta smelt would have a net benefit from BDCP.”

Longfin smelt have a similar life history; they spawn and rear in the Plan area, and then move out into the bay. “For longfin smelt, the primary adverse effects are exposure to contaminants again from restoration or from construction and water activities. But on the beneficial side, this is a food-limited species, and the BDCP is providing substantial access to new tidal habitat and food. … There is some uncertainty with this conclusion, however, because of the volume of habitat and where it’s being proposed, we do believe that there is a great potential for an improvement here.”

The salmon spawn upstream, and use the Delta for rearing, so most of them only spend a portion of their lives in the plan area. The different salmon runs have similar patterns but different life histories, so each fish species is evaluated separately, Ms Pierre explained. “What we found is that the fish that use the Sacramento River area for spawning generally have similar types of effects, and the fish that use the San Joaquin River generally have similar types of effects, especially in the plan area. So we’ve grouped them this way for the purposes of this presentation but they are all evaluated separately.”

The Sacramento River Chinook and steelhead will have much greater access to the Yolo Bypass for migration and for rearing, and the increased tidal wetlands in the plan area along their migratory corridors provide additional food, rearing, resting areas and near shore habitat through our channel margin and riparian restoration. “Similar to the smelt, we have increased food availability, reduced entrainment, and in the case of the Chinook and steelhead, we see reduced entrainment around 50% on average, so it’s a pretty substantial reduction in entrainment. We’re also improving their migration by reducing their entry into the interior Delta which has been known to be a bad neighborhood,” she said, noting that the species will also benefit from conservation measures designed to reduce predators and illegal harvests.

The BDCP’s adverse effects on the Sacramento River Chinook and steelhead are primarily driven by the north Delta intakes: “They are being designed so that there would be no entrainment, but we have identified their actual impingement or otherwise physical contact as a potential adverse effect. The reduction in flows because of the diversion may create predator hot spots or otherwise disorient fish in a way that makes them more susceptible to predation. And again we think we can offset at least a portion of this through localized predator reduction but we are identifying that as an adverse effect,” she said, noting that there is also potential for impacts from construction and maintenance activities, as well as contaminants from restoration; the construction activities are being timed to avoid the peak periods of fish migration and presence.

The BDCP’s adverse effects on the Sacramento River Chinook and steelhead are primarily driven by the north Delta intakes: “They are being designed so that there would be no entrainment, but we have identified their actual impingement or otherwise physical contact as a potential adverse effect. The reduction in flows because of the diversion may create predator hot spots or otherwise disorient fish in a way that makes them more susceptible to predation. And again we think we can offset at least a portion of this through localized predator reduction but we are identifying that as an adverse effect,” she said, noting that there is also potential for impacts from construction and maintenance activities, as well as contaminants from restoration; the construction activities are being timed to avoid the peak periods of fish migration and presence.

The San Joaquin River salmon and steelhead stand to benefit even more than their Sacramento River fish, said Ms. Pierre. “They experience the same beneficial effects from food availability, channel margin and riparian habitat as well as increased access to tidal habitat. They also have substantially reduced entrainment in the south Delta, and better migration, reduced predation and reduced illegal harvest. They don’t have access to the Yolo Bypass like the Sacramento River fish, but they don’t have any exposure to the north Delta intakes,” said Ms. Pierre.  There are adverse effects related to in-water construction activities associated with restoration, and the Head of Old River Barrier is something that would occur that could affect the fish on the San Joaquin River.

There are adverse effects related to in-water construction activities associated with restoration, and the Head of Old River Barrier is something that would occur that could affect the fish on the San Joaquin River.

“As I mentioned earlier, the BDCP does not propose any changes in Shasta operations, but some of our models are showing a difference in Sacramento River flows, and we are looking into that because we are not certain what the mechanism is for that. We will hopefully be sorting that out for the next draft,” said Ms. Pierre. “All of the NMFS criteria that are currently in place would be met with the same frequency as they are now on the Sacramento River, so the effects analysis does not find that there adverse effects on winter run in the Sacramento River.”

“For spring run salmon, we aren’t finding any effects in their primary spawning ground in the Sacramento River or the low flow channel of the Feather River. However, under the high outflow scenario which is the scenario which provides for greater outflow in the spring and the fall, we do have some temperature increases in critical years in those very dry years in the Feather River. However, similar to the Sacramento River and winter run, all of the NMFS criteria are met at same frequency under BDCP as they are without it,” she said.

“For the Sacramento River fall and late fall Chinook, we would actually improve spawning and rearing habitat in the Feather and the American Rivers,” noting that one of the models is predicting a small reduction in rearing habitat in the Sacramento River, but like the other two species, the NMFS criteria are met at same frequency under BDCP as they are without it. “On the Feather River, we do see reductions in rearing habitat on the high flow channel, but this isn’t really where the steelhead spawn; they spawn mainly in low flow channel, and again all of the NMFS are met.” So the BDCP provides a net benefit to the Sacramento River Chinook and steelhead: “We have improved Delta conditions in the plan area, we have the Yolo Bypass, we have increased restoration, we have increased food, reduced predation and all of those benefits, and we don’t’ find that any of the upstream effects are offsetting this.”

“On the San Joaquin River, we have no upstream effects and we are substantially improving the south Delta and San Joaquin migratory route conditions through habitat restoration and reduced entrainment and everything else previously mentioned,” said Ms. Pierre.

Splittail spend most of their life in the plan area, and they need floodplain for rearing and spawning, said Ms. Pierre. The restoration of the Yolo Bypass greatly contributes or benefits this species, but in addition, they have improved food, experience less entrainment and improved passage through the Plan Area. “Like the other species, they have a potential exposure to contaminants through restoration … There are some reductions in flows just downstream of the north Delta intakes and that may have an effect on some migration flow, but we did not find those were of a magnitude to offset the substantial net benefits that we see for splittail.”

Splittail spend most of their life in the plan area, and they need floodplain for rearing and spawning, said Ms. Pierre. The restoration of the Yolo Bypass greatly contributes or benefits this species, but in addition, they have improved food, experience less entrainment and improved passage through the Plan Area. “Like the other species, they have a potential exposure to contaminants through restoration … There are some reductions in flows just downstream of the north Delta intakes and that may have an effect on some migration flow, but we did not find those were of a magnitude to offset the substantial net benefits that we see for splittail.”

Green and white sturgeon spend differing times in the plan area so we looked at these two species separately as well, based on their timing of when they were in different locations, said Ms. Pierre. “For sturgeon, a couple of their major stressors have to do with illegal harvests, and passage into the Sacramento River once they’ve entered the Yolo Bypass and in each of these instances, the BDCP substantially improves those conditions through bypass floodplain improvements and through the conservation measure that addresses illegal harvests. They also rear in the Delta, they are benthic, and they would also experience increased food and habitat availability.”

“For the green sturgeon that spawn in the Feather River in the spring, one of the major ecosystem effects of the BDCP are increased spring flows in the Feather River, and so we think green sturgeon especially will experience spawning flows that could be of great benefit to them. … Given the reduced illegal harvest, substantially improved passage and the spawning flows as well as the rearing habitat in the Delta, and given the time that they spend in the plan area, we also found that each of these species experienced a net benefit from the BDCP,” said Ms. Pierre.

“For the green sturgeon that spawn in the Feather River in the spring, one of the major ecosystem effects of the BDCP are increased spring flows in the Feather River, and so we think green sturgeon especially will experience spawning flows that could be of great benefit to them. … Given the reduced illegal harvest, substantially improved passage and the spawning flows as well as the rearing habitat in the Delta, and given the time that they spend in the plan area, we also found that each of these species experienced a net benefit from the BDCP,” said Ms. Pierre.

“River and Pacific lamprey spent very little time in the Delta. They basically migrate through as young after they’ve spent some time in upstream habitats and in general, we don’t really affect them except for that we do reduce entrainment and we do provide some increased migration flows for them as they move out of the Delta’, she said. “So we did find that based on their exposure in the Delta and to the BDCP and the types of changes they would experience that they would also each of these species experience a net benefit from BDCP.”

—————————

Comment by Anne Spaulding, city of Antioch: “You say salinity has no biological effect and the fish are protected, but western Delta water supply and quality is not protected. … “From Chapter 5.6.28.1.5 salinity, “Most significantly affected will be Suisun Bay and the west Delta … salinity is expected to increase by 10 to 50 percent in Suisun Bay and the west Delta in addition to what would have been expected without the BDCP.” Obviously 50% is a huge salinity increase. We did not find more detail in appendix 5.C, but that 50% increase in salinity in July through October is, according to our modeler, massive, and if that’s calculated as a long term average, some years will be even worse than that.”

Jerry Meral answered that water quality will be addressed in the EIR/EIS that is coming soon.

Question from Tom Stokely through internet: He asks modeling of the Trinity Reservoir appears to use a minimum carryover storage of 240,000 acre-feet, but the NMFS biological opinion requires 600,000 acre-feet minimum as of September 30. … Which one will we be using … 600,000 or 240,000 ?

Federico Barajas answers: “Part of what we’re going to be doing and what’s been modeled to date is the rod flows under the Trinity requirements. So the Trinity requirements under the rod are essentially the foundation that we are employing for the BDCP modeling and so the results that we’re presenting here today are under that foundation, so we’re basically meeting those requirements for the Trinity.”

Question from Dr. Craig Lusker, a resident of Discovery Bay, who wanted to know why desalination was not being considered, given the advances in technology that have reduced costs. “I live in Discovery Bay, I don’t want to live in Discovery Meadows. I did not see anything up there that said anything up there about the most endangered species that’s near and dear to my life, and that’s the human Discovery bay fish: myself, my family and my neighbors.” Meral responded that desalination was still rather costly, had impacts, (etc.) Dr. Lusker stated that he did not believe Meral and would like to see a study done on that.

Bob Wright representing Friends of the River, Restore the Delta, and the Environmental Water Caucus addressed his comments to the agency officials from NMFS, USFWS, and DFW: “ … Scientists and responsible fishery agencies know and maintain that the Delta and the river and the fish require more freshwater, not less. If a place needs more fresh water not less, it defies common sense to build massive public works projects with the capacity to take 15,000 cfs out of the Sacramento River. … That defies common sense for an area like the Delta that needs more fresh water. The effects analysis you have before you is not worth the paper it’s printed on, and I’m not attacking the qualifications of the abilities of the people who prepared it, but it’s been prepared by the folks that want to take the water. … The easiest solution to the problem you face at the two federal fish agencies and CDFW is to follow the state law and bring a halt to this process and get the answers from the SWRCB. … They are supposed to be setting new, stricter flow objectives to save the fish and save the Delta and they will do that. This whole thing is simply a scheme to try and get the tunnels underway so that by the time the State Board would act, it would be like a fait accompli. You should require funds be made available so you can have an independently prepared effects analysis that isn’t under the thumb of the agencies that want to take the water and the exporters who want to get it.”

Question from Barbara Barrigan-Parilla: “BDCP has fairly low assumptions of sea level rise under climate change, 6” by 2025, 18” by 2060, if BDCP is only planning for 18” sea level rise by 2060, why is BDCP making such a major emphasis on habitat at much higher elevations? If you think there is likely to be higher sea level rise, why aren’t you considering that in your reservoir output scenarios, is it because it would require increased outflow? And why isn’t there a study on what could be done with fortifying levees if you think sea level rise is going to be higher?”

Jerry Meral answers: “It is very speculative for any of us to say we know what SLR is going to be; it’s certainly happening. That’s our best guess as to what we should be modeling for. The plan only goes for 50 years, most of the sea level rise will continue on well beyond that period. We tried to strike an intermediate balance in terms of accommodation … we’re open to suggestions that we should allow more accommodation if that’s what you’re suggesting.”

Barbara Barrigan-Parilla counters that it’s a consistency issue; other state plans and documents are talking about significant sea level rise, and those types of inconsistencies make us wary of your modeling.

There was a question regarding the amount of water that would be diverted and how that would affect the flow of the Sacramento River.

Jennifer Pierre said that through winter and most of the spring, around 20% of the flow of the Sacramento River water in a wet year, increasing in June and the summer and sometimes in October; wet years, based on our analysis don’t appear to be the problem; there’s a lot of diversion capacity and there is still a lot of water left in the river.

In the drier years, the bypass flow requirements, the requirement that a certain amount of water pass by the intakes, mean that the north Delta intakes can’t be used, so in drier years, the south Delta intakes are used. It’s really the middle years, the above or below normal years, and similar to wet years, on average, we’re taking under 20% of the Sac River water, and sometimes in June and in the fall a little bit more than that, but always the maximum that can be taken is based on the maximum river flow at the time that diversion is occurring, she said, pointing out that there are graphs in appendix 5-b that demonstrate the different splits between north and south delta pumping compared to existing conditions and across water year types, she said.

Jim Provenza, Yolo County Supervisor, commented regarding floodplain restoration in the Yolo Bypass: “We still need to address the issue of the flooding with 17,000 cfs per second through June, because if we do that, the farmer can’t plant the rice. … We’re concerned as you are about fish benefits, but we’re also very concerned about agriculture, about the impact on rice growing and the impact on other crops, such as tomatoes, in the Delta.” There are significant economic impacts if there is flooding every year through June, about $9M in economic impacts, maybe a point where it would go away entirely. … “There are various alternatives, but if none of those are looked at, we really do face a significant impact on our economy and I think on the success of your project.” Jumping ahead to governance, “Yolo County believes it’s essential that local government be included in a significant way in the governance process. If we go forward with the current proposal, there’s no inclusion of local government in any significant way. There would be less involvement of local government of any HCP ever in the nation. We will be submitting a written proposal to you in the near future and we ask that you take a close look at that because we don’t this can work without our involvement…. If local government isn’t there as a coequal branch – you’ve got the federal government and the state government right up there in the governing model – but without the local government, it just isn’t going to work.”

Jerry Meral answered: We are looking forward to the proposal from the Delta Counties Coalition to give us some governance models that would work on the local level.

——————————————————

Ellen Berryman, ICF International, then presented the details of the plan’s effect on natural communities and terrestrial species.

Section 5.4 of the plan talks about the Plan’s effects on 13 natural communities, she said. “One of them is cultivated lands which you wouldn’t normally think of as a natural community, but the term is used consistent with terminology under the NCCPA because we do have covered species that do depend on the cultivated lands.”

There are 45 terrestrial covered species in the BDCP including 5 mammals, 11 birds, 2 reptiles, 2 amphibians, 7 invertebrates and 18 plants. The methodology we used to quantify impacts was to develop habitat models taking into account life history requisites, habitat value, and other factors. The data to quantify effects included a footprint layer for the water facilities and hypothetical footprints for the tidal and floodplain restoration using GIS data, said Ms. Berryman.

There are 45 terrestrial covered species in the BDCP including 5 mammals, 11 birds, 2 reptiles, 2 amphibians, 7 invertebrates and 18 plants. The methodology we used to quantify impacts was to develop habitat models taking into account life history requisites, habitat value, and other factors. The data to quantify effects included a footprint layer for the water facilities and hypothetical footprints for the tidal and floodplain restoration using GIS data, said Ms. Berryman.

Ms. Berryman then highlighted the results of the effects analysis on four of the Plan’s 13 natural communities.

For tidal brackish emergent wetland, there are 8501 acres present in the Plan area, and there will be at least 3000 acres restored, an increase of 35%. Restoration will be located in areas consistent with the tidal marsh recovery plan developed by the US FWS. The endangered salt marsh harvest mouse uses this type of habitat, and would benefit by increases in habitat. The Suisun Marsh aster is a plant that occurs in the tidal brackish emergent wetland would also benefit by the increased acreage.

For tidal freshwater emergent wetland, there are currently 8,953 acres in the plan area; about 21 of those acres would be permanently or temporarily lost. However, the BDCP is proposing to restore 13,900 acres, or an increase of 155% over what currently exists. The Black Rail is a bird species would benefit by the increase the increase in habitat.

There are currently 18,132 acres of the riparian natural community currently in the Plan area. Under BDCP, about 5% of the existing natural community would be permanently loss, and another 1% would be temporarily lost, but the BDCP would restore 5000 acres, which would be an increase of 28% over current acreage. The restoration will be located in areas mostly within the floodplain that promote connectivity with restoration and management geared toward maintaining structural heterogeneity and biodiversity. The riparian brush rabbit is an endangered species nearly endemic to the plan area, which would benefit from the large increases in habitat.

There are 506,526 acres of cultivated lands in the plan area; there would be a permanent loss of 55,800 acres, or 11%. However, the protection of 45,405 acres with conservation easements that provide habitat for covered species, including lands for Swainson’s hawk. Conservation easements would require maintenance of appropriate crop types of the covered species.

——————————————

Comment by Osha Meserve:” I’d like to make a comment on behalf of Stones Lake NWRA. … We’re very concerned about impacts on terrestrial species from this project. … There’s a real devastating effect on birds, internationally protected birds like the greater sandhill crane and others, and so we’re very concerned about the timing of when the impacts occur, especially from conservation measure 1, the conveyance facilities. … Is that really going to make it viable for the cranes and other important migratory birds that come through our area to be able to continue to exist? It’s really important that there not be any gap. They need to have the place to come to at the time that they’re flying through the area.”

Jerry Meral:”Tthose are critical issues. We cannot come to a conclusion that we’re damaging those species even temporarily to the point where they’d be suffering and not contributing to their recovery,” he said, noting that they would be meeting with Osha and Stones Lakes representatives the next day.

Question, follow up from Tom Stokely: “Will the BDCP use the modeling with the September 30th 600,000 acre-feet carryover storage requirements for the Trinity River according to the year 2000 NMFS biological opinion?”

Federico answers: “Yes, that is the baseline that we’re using under the BDCP and that is the number that would be the basis not only for the proposal and also for the no-action alternative.”

CHAPTER 6 PRESENTATION

Dr. David Zippin continued with the details of chapter 6. The schedule and requirements for habitat restoration and protection of natural communities is covered in this chapter. The plan is required to complete restoration by year 40, which would leave 10 years at the end where the restored lands can be monitored and corrections made, if necessary, before the end of the permit period, Zippin said.

Dr. David Zippin continued with the details of chapter 6. The schedule and requirements for habitat restoration and protection of natural communities is covered in this chapter. The plan is required to complete restoration by year 40, which would leave 10 years at the end where the restored lands can be monitored and corrections made, if necessary, before the end of the permit period, Zippin said.

The reporting section describes some of the annual documents that we’ll be required to produce, including a work plan, an annual budget, an annual water operations plan progress report and a water operations report. These will all be public documents, Dr. Zippin said. “There will also be a 5 year cycle where there will be a more comprehensive review from outside independent parties, both on the finances of the plan as well as the scientific underpinnings and progress of the plan in moving towards meeting its biological goals and objectives.”

Regulatory assurances are covered in Chapter 6; this is the basis for habitat conservation plans. “The shorthand is they are called ‘no-surprises’ or a deal is a deal. These arose back in the Clinton Administration in the early 90s so they’ve been around for awhile. They are the foundation and one of the incentives for applicants to pursue habitat conservation plans,” Dr. Zippin said. “What it means in basic terms is that the federal agencies won’t require additional conservation or mitigation for anything that is not described in the plan, or what’s called unforeseen circumstances. We do have to anticipate changes in the environment that could occur, and one of them certainly is climate change,” he said, noting that funding must be provided for dealing with changed circumstances.

“The federal agencies always retain the ability to suspend or revoke the permits in the event of any one of our covered species in jeopardy of extinction, and there have been cases of permit suspension. It’s a rare event, because I think the federal agencies always work with the applicants to make sure the plans are implemented properly, but one of the few examples of a permit suspension actually happened here in Sacramento at the Natomas Basin HCP just northwest of the city, so we have a local example of that actually occurring, and it helped to reverse that plan and set it back on course.”

He noted that the NCCPA has a very similar provision for no surprises, and also has the same exception where the state could suspend or revoke the permit in the event of possible jeopardy.

Changed circumstances that are evaluated include reasonably foreseeable changes in the environment that could result in a change in the status of the species, such as nonnative species. “Nonnative invasive species are a problem already but we anticipate or describe our responses if, for example, new invasive species colonize the Delta,” Dr. Zippin said. “Unforeseen circumstances are everything else that we have not described in the plan. We tried to be as clear as possible of where that line is, where for example a reasonable foreseeable flood and beyond that don’t consider reasonably foreseeable.”

Changed circumstances that are evaluated include reasonably foreseeable changes in the environment that could result in a change in the status of the species, such as nonnative species. “Nonnative invasive species are a problem already but we anticipate or describe our responses if, for example, new invasive species colonize the Delta,” Dr. Zippin said. “Unforeseen circumstances are everything else that we have not described in the plan. We tried to be as clear as possible of where that line is, where for example a reasonable foreseeable flood and beyond that don’t consider reasonably foreseeable.”

“The plan changes are certainly important. There have been HCPs that have been around for 20, 20 years. San Bruno Mountain’s HCP is the first one in 1982; it has gone through several plan amendments since its inception so this is a fairly common process, although for a formal amendment you do actually have to go through a formal process; public review of the amendment, environmental compliance document, perhaps an EIR/EIS to approve that amendment”, he said. “There are other ways to change the plan if they don’t rise the level of the amendment through administrative changes or minor modifications with approval of the state and federal wildlife agencies.”

—————————————–

Bob Wright, Friends of the River, Restore the Delta, and the Environmental Water Caucus: speaking specifically to state and federal wildlife officials,” all scientists and responsible agencies say the Delta needs more fresh water not less, and this plan to take massive quantities out of the river upstream. It would have a big red flag or stop sign. … The regulatory assurances are an ‘incredible tying of hands of the two federal fish agencies responsible for trying to save the declining endangered species of fish. If you go forward and you are part of this take permit, that means that the federal government will not require additional conservation or mitigation measures, or restrictions on the use of resources including water, even though as everybody really expects, this plan is going to be the death knell for a number of these endangered fish species. And also if there’s an unexpected decline, the primary obligation for undertaking additional conservation measures rests with the federal government. … the no suprises rule … you would be contracting away your section 7 away and all the powers you have under that, you could not require additional water or other natural resources not called for under the plan. “This is bonanza for the water exporters at the expense of the Delta and the endangered fish species … this is just an absolute disaster in the making, and we request that it go no further, that you bring a stop to it, and no regulatory assurances.”

Mike Tucker, NOAA answers: “Bob, I actually agree with a lot of what you said there, and I guarantee you that we have our legal people look at it, I guarantee you that we are not going to relinquish any of our section 7 authority or requirements. No federal agency can do that under any permit. … we are reviewing this document too and we are putting together our comments, and we have seen language in here that we have issues with that we will be working with the applicants to make sure we remedy all the issues. You are right that we cannot relinquish our ability to make sure that we can manage this plan in a way that we maintain control over the biological outcome of the plan. I guarantee you that’s what we are working on and that were not going to relinquish any of our legal abilities.”

Question: how does the BDCP compare to other HCPs?

Dr. Zippin answered that this is the largest aquatic HCP in the country, but there are other plans that focus on different types on development activities that are actually much larger, such as a plan currently in development involving 8 states in the upper Midwest addressing wind development, or timberland activities in the Pacific Northwest. “I would say we’re about in the middle of the road in terms of acreage size, but in also in terms of the numbers of species we’re covering, it’s about an average number; but in terms of aquatic HCPs, we’re certainly one of the largest in the country right now.”

CHAPTER 7 PRESENTATION

Chapter 7 describes the structure that will be created to administer the plan, the roles and responsibilities of the various entities that will be involved, as well as the procedures for implementing the strategy, resolving conflicts, public participation and regulatory compliance, Dr. Zippin said. “The governance framework was really the result of very extensive discussions between the state and federal agencies and the state wildlife agency over the last two years. I think Jerry and others here at the table could speak to that process and the very intense discussion that have taken place.”

Chapter 7 describes the structure that will be created to administer the plan, the roles and responsibilities of the various entities that will be involved, as well as the procedures for implementing the strategy, resolving conflicts, public participation and regulatory compliance, Dr. Zippin said. “The governance framework was really the result of very extensive discussions between the state and federal agencies and the state wildlife agency over the last two years. I think Jerry and others here at the table could speak to that process and the very intense discussion that have taken place.”

The chapter identifies and describes the various groups that will govern the plan. ” The Authorized Entities Group are composed of the permittees, the state agency, DWR, that will be receiving the permit, as well as the identified state and federal water contractors. There will also be the permit oversight group, the adaptive management team and the stakeholder council as well as supporting entities that will help to implement the plan but will not be permit holders and we talk about the role of the general public as well,” Dr. Zippin said.

The implementation office will be responsible for implementing all of the conservation measures, doing the restoration work, overseeing the restoration work, implementing the other stressors conservation measures, designing and conducting the monitoring program, and many other tasks that need to be accomplished during the 50 year permit term. It will be overseen by a program manager, a very important position, and the qualifications of that position are described in the chapter, as well as a science manager, the person responsible over overseeing the scientific aspects of this plan which are so critical to its success. The staff are expected to come from existing agencies and existing programs that would simply be rolled into or folded into BDCP, said Dr. Zippin.

The implementation office will be responsible for implementing all of the conservation measures, doing the restoration work, overseeing the restoration work, implementing the other stressors conservation measures, designing and conducting the monitoring program, and many other tasks that need to be accomplished during the 50 year permit term. It will be overseen by a program manager, a very important position, and the qualifications of that position are described in the chapter, as well as a science manager, the person responsible over overseeing the scientific aspects of this plan which are so critical to its success. The staff are expected to come from existing agencies and existing programs that would simply be rolled into or folded into BDCP, said Dr. Zippin.

———————————————-

Question from Anne Spaulding: Is there a role for the Delta Stewardship Council and the Independent Science Board?

Dr. Zippin answered that there definitely is, but that he didn’t think it was in Chapter 7. The Independent Science Board will play an important role in providing independent scientific review, mandated at least every five years as part of the plan.

Jerry Meral added that the DSC had been included in the governance structure, and they said that they were are acting essentially as a regulatory agency here so they can’t be in the governance structure, but they are going to be very involved in the science.

Question from Jeff Michael over the internet: He asks if the species don’t respond positively, it seems the cost of failure falls on the taxpayers and upstream users in the environment and not the necessarily the exporting water agencies. If this isn’t true, explain who would bear the cost of failure.

Meral answers: I think it would depend on what the failure was … but if the failure of one of the CMs was associated with water export, undoubtedly the main burden would fall on them because the exporters would be responsible for changing the level of export. If the failure had to do with one of the terrestrial measures, fpr exa,[;e, riparian restoration measure, then probably if the taxpayers or general public had paid for that measure, then within the limits of what we’re required to do, as David described earlier, that would become sort of a general fund costs. So I think the answer to the question is which part of the plan has failed, it’s a very complex plan, but if it does have to do with export levels, than the exporters would be the ones responsible, the two main exporting agencies.

Jeff Michael also asks: you state some extreme cases where the permit could conceivably be revoked; the more likely outcome is that most of the cost of failure falls on the taxpayers. The HCP shifts risk from water exports to everyone else; should the water users have to compensate the public for shifting of the risk?

Meral answers: I think I sort of answered that in the first question, but if there is a shared risk in a sense because the public participates in financing the habitat part of BDCP, that risk is shared by the exporters because they are also responsible for a substantial part of the terrestrial impacts. There’s no direct requirement that the public be involved with the risks that the water users bear with respect to export. If there is a fish failure, in a sense, that’s going to fall on the water exporters, so I don’t think the water users are shifting the risks to the public. The biggest risks in this project are undoubtedly going to them, so I don’t know that they’d have to compensate the public except to say that they are the public, they are the water users south of the Delta, so their parts of the public will be picking up some of whatever the costs that occur here.

The meeting concluded with a bit of a discussion of what would happen if the permit were revoked. There were a few differing opinions and no concrete conclusion came out of the discussion.

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

- Click here to view the power point presentation for the meeting.

- Click here for the expected outcomes brochure.

- Click here to view the video of the meeting.

- Click here to visit the Bay Delta Conservation Plan website.

WANT TO HAVE A LOOK AT THE BDCP DOCUMENTS BUT DON’T KNOW WHERE TO BEGIN?

- Click here for the BDCP Road Map!