For more than two decades, native fishes in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta have been declining at a rapid rate with no single identifiable cause. “Stressors” are broadly defined as those factors that can harm native species, and the Delta has a long list of them that includes agricultural and urban discharges, invasive species, altered flows, loss of habitat, and of course, water diversions. The PPIC report, Aquatic Ecosystem Stressors in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, focuses on organizing these multiple stressors in a useful way for setting and discussing Delta environmental policy.

While the decline of the Delta’s ecosystem and its native fish species is well documented and not in dispute, the causes and proposed actions to take are the subject of a seemingly endless debate. Oftentimes, the discussion centers on water supply operations in the Delta, but this is not the only possible cause for the Delta’s decline, the report states: “Water flows are indeed the “master” ecological variable in the Delta—an essential component of the aquatic ecosystem—and flows have been dramatically altered by water use and operations. But flows move through and across a landscape that has been fundamentally and irreversibly changed from its original condition. Additionally, contaminants and non-native species are now an integral part of these managed flows and landscape. This new Delta significantly differs from the historical Delta, and the effects of this change on native species are widespread and profound.”

The report classifies the stressors into five general categories: discharges, fisheries management, flow management, invasive species, and physical habitat loss and alteration. Each category has a specified human activity that either initiates or magnifies the stressor. For each stressor group, the report states who’s responsible, the major interactions with other stressor groups, the habitats and species affected, and the major actions that can be taken to reduce stressor effects.

The report focuses on the factors that adversely affect native fishes; it does not address the multiple beneficial uses of water in the Delta or the trade-offs among those various objectives. Ocean conditions are excluded because they are not locally manageable, and climate change is not considered separately as its effects will be manifested in all the stressors.

DISCHARGES

The use of land and water for both agricultural and urban uses results in discharges of substances and contaminants to the Delta’s waterways. These substances can alter water quality, degrade habitat, disrupt food webs, or cause direct harm to native species. All native species are affected by harmful discharges, either directly or indirectly.

Agricultural discharges include both point sources, such as dairies or feeding operations, and non-point sources, such as cropped areas and rangeland; irrigation and tilling activities that leach and discharge dissolved solids to adjacent rivers; and the application of saline groundwater, fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides that adds other dissolved solids to the excess water that is discharged to adjacent waterways.

Municipal wastewater discharges can include salts, excessive nutrients, pharmaceuticals, personal care products and pesticides. Stormwater discharges can contain varying levels of petroleum products, heavy metals, fertilizer, herbicides and pesticides. Other sources of urban discharges include non-point runoff from residential and industrial areas.

Drainage and runoff from abandoned mines, especially on the eastern slopes of the Coast Ranges, continue to contribute mercury to the Delta, and disturbance of mercury-contaminated sediments can cause high background levels of mercury in the Delta.

All of these discharges interact with other stressors, most substantively with water flows as reductions in flow as a result of both upstream diversions and current export pumping practices causes increases in the concentrations of contaminants and degradation of water quality. Additionally, increases in nutrients can create or enhance conditions that are favorable for non-native species.

There is much debate over how much agricultural and urban discharges are contributing to the Delta’s problems. Major concerns are the effects of pesticides on food webs, ammonia discharges from wastewater treatment plants, selenium and salts from the San Joaquin Valley, and constituents of emerging concern, such as pharmaceuticals and other non-regulated chemicals.

Contaminants from discharges have been documented in all of the Delta’s major aquatic habitats. The Central Valley Regional Water Quality Board, the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Board, and the State Water Resources Control Board are responsible for setting water quality standards for waterways within their respective jurisdictions, and for developing Basin Plans to meet those standards.

FISHERIES MANAGEMENT

Hatchery operations have been a mixed blessing. Used to mitigate the effects of overfishing, habitat destruction and the loss of spawning habitat, hatcheries have sustained fisheries for decades, but have done so at the expense of wild populations.

Displacement and interbreeding by hatchery fish contributes to the reductions in wild populations, and hatchery fish are less well-adapted for reproducing and surviving in the wild, making them more vulnerable to unfavorable wild conditions.

The report recommends changes to hatchery operations: “[P]olicies governing salmon and steelhead hatcheries need to be reformed to make fisheries sustainable and to maintain wild populations. This reform may involve separating the production functions of hatcheries to support fisheries from the conservation functions to sustain natural populations … This may entail reducing or eliminating hatchery production, allowing for only wild salmon spawning in the rivers of the Central Valley. The consequences of shut a shutdown would be large for commercial fisheries, and might be mitigated by moving hatcheries to coastal rivers and streams.”

FLOW MANAGEMENT

Flow management involves the diversion, retention, or manipulation of water within and upstream of the Delta to support water supply needs, flood management, or ecosystem improvement.

Flow management affects all major aquatic and terrestrial habitats in the Delta, and is ‘broadly inferred’ to be a stressor when it changes the historic flow regime, limits access to or the quality of critical habitat, or promotes conditions that are better suited to invasive species at the expense of native species.

Freshwater inflows and tides are the two sources of water movement in the Delta. These flows support and connect dynamic habitats, supply sediment and energy needed to shape those habitats, as well as control the salinity gradient and water temperature. The Delta’s native species are well-adapted to these variable conditions.

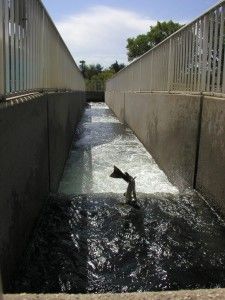

However, water management has fundamentally changed the natural flow regime of the Delta. Winter and spring inflows and outflows have been significantly altered, and the introduction of cross-Delta flows and reverse flows in some channels has led to high fish mortality at the export pumps.

These changes have not been without consequences, the report notes: “Prevailing ecological theory argues that the magnitude of these alterations can be linked to declining native species, either directly or through changes to habitat, water quality and food webs. Direct and circumstantial evidence, such as species declines during droughts, supports this conclusion.”

The responsibility for these negative effects lies with upstream diversions of water for farming or municipal use, in-Delta water users and diverters, and the water export operations of the Central Valley Project and the State Water Project. Additionally, there are also large local utilities that remove water from the Delta or by upstream diversions. The State Water Resources Control Board, California Department of Fish & Game, National Marine Fisheries Service, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Environmental Protection Agency all have regulatory responsibilities.

Flow is a major component of the ecosystem, the report notes: “Flow in the Delta drives all ecosystem functions and interacts with all of the other groups of stressors. The most notable interaction is between flow and physical habitat. Landscape changes resulting from reclamation and flood management infrastructure have, in combination with changes in flow, eliminated the historical hydrologic connectivity of floodplains and aquatic ecosystems in the Delta and its tributaries, degrading and diminishing Delta habitat for native plant and animal communities. The large reduction of hydrologic variability and physical complexity has, in turn, supported invasions of alien species that have further degraded conditions for native species. Flow regime changes have also accentuated the effects of degraded water quality on native ecosystems. The combination of these factors makes today’s Delta a novel ecosystem that appears to have undergone an ecological regime shift unfavorable to native species.”

However, with California’s extensive water infrastructure, there are many options for improving flow management: coordinated releases from upstream dams could recreate more natural flow regimes such as winter flood and spring snowmelt pulses; temperature and salinity could be managed through coordination of exports and inflows to maximize habitat in the Western Delta; and seasonal and interannual variability could be increased to suppress invasive species and promote native species.

INVASIVE SPECIES

One of the most invaded estuaries in the world, the Bay-Delta is home to more than 250 exotic plants and animals.

And they appear to be increasing in number: a new one is estimated to arrive every 24 weeks. Invasive species arrive in the Delta by a variety of ways: historically, some were introduced intentionally to create commercial or recreational fisheries, but most have probably arrived through ballast discharges, boating activities, and illegal introductions by anglers.

All of the Delta’s waterways have been affected by invasive species. These invasive plants and animals affect the ecosystem either by causing physical changes to the habitat or by reducing the quality or quantity of food available for native species. Once an invasive species is introduced, it can only be managed but rarely eradicated.

Assigning responsibility for invasive species is difficult as no single agency has responsibility for managing them. The Department of Fish and Game has responsibility for preventing new introductions and for managing non-natives that could be harming native populations, but the agency lacks sufficient funds and personnel to effectively carry out those responsibilities. Other agencies have limited responsibilities. While an official Aquatic Invasive Species Management Plan was adopted in 2008, implementation requires complex coordination and funding, and thus has had little effect so far.

Possible actions that could be taken to address the problem include enforcement and expansion of state and federal laws to manage ballast water discharges as well as mandatory inspections and cleaning of boat hulls. Changes in water flow operations to increase variability in conditions and managing nutrients can create conditions that are less favorable for invasive species.

PHYSICAL HABITAT LOSS OR ALTERATION

Since the mid 1850s, the Delta has been dramatically altered, with reclamation of the land leading to the loss of roughly 95% of the Delta’s original tidal marsh and floodplain habitat.

Most of these changes have been detrimental to native fish species. Land reclamation has eliminated the complex physical habitats that supported diverse populations of native species; the habitat that remains consists of relatively deep channels, disconnected remnants of tidal marsh and floodplain, and mid-channel islands. The majority of the Delta’s levees have been lined with rock and have little riparian vegetation and little habitat value.

“The scale of alteration in the Delta landscape is an underappreciated stressor in current debates over the Delta ecosystem, which tend to focus principally on flows,” the report says.

The report also states that aspects of the Delta can likely never be restored to pre-1850s conditions: “The characteristics of the earlier Delta that are likely gone forever include (1) physical habitat appropriate for species that tend to rely on shallow water and structure for refuge and feeding; (2) food aggregation that long, complex sloughs and channels provide through increased production and retention, and (3) cooling functions that adjacent wetlands provide for small water bodies, such as sloughs, which provide refuge for fishes during summer heat spells.”

The loss or disruption of physical habitat interacts and amplifies all other stressors, especially flow management. However, managing water flows to support native species is less effective if there is insufficient connectivity and habitat complexity to support those flow changes.

Changes to land use behind levees constrain options for increasing habitat; land targeted for habitat restoration must have the right combination of land elevation, appropriate flows, sediments, nutrients, and tidal energy. Deeply subsided areas in the central and western Delta cannot be restored to tidal marsh within a reasonable time frame; however, there is potential for restoration of marsh, floodplain and riparian habitat in the north and south Delta. Flow management along with alterations to the levees to restore hydrologic connections can improve habitat conditions.

CONCLUSION

Decades of monitoring and research have determined that multiple stressors are responsible for the long-term decline of native fishes in the Delta. The most difficult scientific problem is identifying the many causes for the decline of native species and then deciding the most effective response. Scientific approaches to studying the Delta have been so far unable to provide the definitive answers the policymakers and the public want, although newer approaches show promise for eventual use. However, the Delta will continue to experience major changes, and so all approaches suffer from a common problem, the PPIC report argues: “They focus on current or historical conditions in the Delta and have not been used or cannot be used to examine a future, reconciled Delta that meets both human needs and those of the ecosystem as well.”

The Delta has a long history of having policy needs that outpace the development of scientific tools that can adequately answer the questions with the desired certainty, but nonetheless, policymaking must proceed: “Complexity and uncertainty have often been used as an excuse to avoid action. Additionally, any single action, even if deemed beneficial for the fish, is usually confronted by a stakeholder or interest group opposed to its realization, thus making collective actions even more difficult. Yet maintaining the status quo appears to be the least likely avenue to successfully managing the Delta’s native biodiversity.”

The Delta’s many stressors affect resident and anadramous fish species, including the Delta smelt, juvenile Chinook salmon, and many others: “Changes in water quality, loss of habitat, and alteration of flow regime appear to have the broadest and most direct impact on native species. However, other contributors of stress include the many invasive species that are damaging the food webs and physical habitats of native species, and the practices of fisheries management (and in particular the hatcheries) that are damaging wild populations of salmon.”

In a “stressor pays” scenario, ideally identifying responsibility for stressor impacts would be easy. However, in the Delta, responsibility varies; some stressors, such as water quality impacts from discharges, are the result of current activities, and direct allocation of responsibility is often possible; other stressors, such as land reclamation, are the result of historic practices, although there are those who receive economic benefit from its continuation and thus bear some responsibility. And yet other stressors, such as invasive species, have no real identifiable responsible party.

The report concludes: “In future work, we hope to use this classification of stressors and potential remedies to inform discussions on how to prioritize ecosystem investments and to allocate responsibility for supporting these investments. Both issues present major policy challenges for California, and solutions to these challenges are needed to support a more promising future for the Delta’s aquatic ecosystem.”

- Click here to read the full report, Aquatic Ecosystem Stressors in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

NEXT ON THE NOTEBOOK: I’ll take a look at a plan the PPIC has for managing the Delta and meeting the coequal goals.